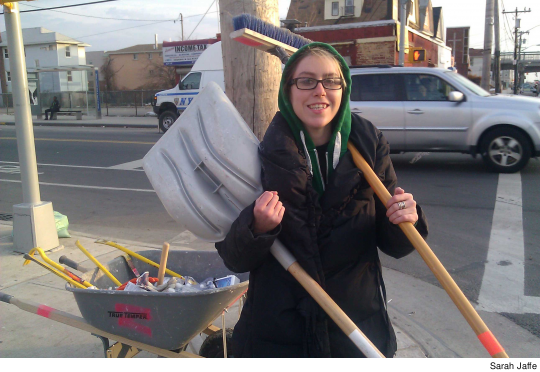

On Friday morning, November 30, a group of Brooklyn College students and faculty, dressed in layers of denim and sweatshirts, piled into a van headed to Far Rockaway for a day of hard labor on homes flooded by Superstorm Sandy.

The “Sandy Solidarity Caravan” was organized by Emma Francis-Snyder and S. Thompson, members of the Brooklyn College Student Union. The van rental was paid for by the PSC chapter to support the joint effort, and Jocelyn Wills, associate professor of history, was at the wheel.

|

The group of 10 volunteers was headed out to work with Respond and Rebuild, an organization of experienced disaster relief volunteers doing demolition and cleanup of flooded homes. “Many people’s lives will never be the same,” Francis-Snyder told Clarion. “To get money to rebuild their homes they’ll have to make endless phone calls, file paperwork that’s never [considered] correct, and run around in circles trying to achieve some sense of normalcy that will take years at best.” The students and faculty who joined the caravan said they knew that donating a day of work wasn’t going to make people’s lives normal again, but they hoped it would provide some concrete help and perhaps help victims feel less alone.

|

Demolition Work

For PSC members Carolina Bank-Muñoz and Emily Molina, both assistant professors of sociology, this was their first time doing demolition work, but some of the students involved had done it before: Francis-Snyder spent 2008 and 2009 doing construction in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina, and she and Thompson were involved early on with Occupy Sandy, the relief effort spearheaded by members of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Respond and Rebuild is one of several groups connected with Occupy Sandy, which have taken up the challenge of recovery work where official response has been lacking.

The Brooklyn College community has been involved in various ways in Sandy relief, Thompson explained, such as coordinating donations of money and items. The student union took up the task of providing “people power,” helping to bring volunteers to the Rockaways to do demolition work. Given what she knew about FEMA and other disaster relief agencies from her time in Louisiana, Francis-Snyder said, “I knew that if other people didn’t do the work, it wouldn’t get done.”

“The effects of Hurricane Sandy are already fading from people’s memory,” she said, though the recovery will no doubt take years, and residents are still cleaning out flood-damaged homes. “If we provide people an easy way to plug in and provide their services, more people will sign up and keep coming.”

In Far Rockaway, Respond and Rebuild had established a hub for volunteers with tables piled with safety equipment and shovels, brooms and crowbars stacked against a wall. The Brooklyn College group was split into separate work crews and sent to two houses with a wheelbarrow full of supplies each. In one house, no work had been done yet and the crew had to completely demolish the basement, pulling down wall tiles and the drop ceiling (and finding quite a few spiders and bugs in the process).

In the other, belonging to Joe Nathans White, demolition had already begun on the first floor and the crew was there to finish the job, pulling up tiled floors and knocking out the remains of soggy Drywall, pulling nails from the wall and cleaning up the mess. White bought his house almost 40 years ago. He’s retired now and had planned to sell the home, but his children wanted to keep it. His daughter, Melissa, a local schoolteacher, arrived as the crew worked and talked with them about the school where she works and its problems with mold. The flooded first-floor apartment had been hers, and she was staying with her boyfriend in another part of Queens, leaving her with a two-hour commute to her job in the Rockaways.

For Molina, who is in her first semester teaching at Brooklyn College, this was the moment that stuck with her – meeting the family, hearing their stories. As a newcomer to New York, she felt that she didn’t know the affected communities very well, but wanted to do something to help mitigate the crisis.

Connecting with the affected communities was very important to everyone on the caravan, and on the way out to the Rockaways, Francis-Snyder and Thompson facilitated a discussion of the practice of mutual aid.

How to Respond

“Mutual aid is the exchange of resources and services in a way that is both voluntary and mutually beneficial to those involved. It’s really important to go into this work with a grounded understanding that everyone deserves to live a dignified life,” Francis-Snyder explained. “I’m not doing this because I feel guilty, and neither should you.”

Housing issues and inequalities are at the center of Molina’s academic work, and that contributed to her desire to get involved with the caravan. “I study foreclosures – disproportionate foreclosures,” she told Clarion. “Some neighborhoods are more impacted than others and there’s a reason for that. It’s similar…to why some neighborhoods were more impacted by Sandy: I see both of those things as social disasters. There’s always going to be uneven impact of disasters, because of how we organize socially.”

Thompson pointed out that this kind of inequality is at the core of the problems laid bare by Sandy. “The hurricane revealed the crisis and made it more apparent to the people outside the communities that were experiencing it,” she said. Inequality showed in the construction of the homes in Far Rockaway and in which neighborhoods had seen better responses from FEMA and the Red Cross. The response of volunteer groups with far fewer resources, like Respond and Rebuild, Francis-Snyder said, has been superior in many ways to the well-resourced institutions.

“It was a great initiative by students to do this. I was really happy that they were initiating something and that the union could support and participate in it,” Bank-Muñoz said. “The larger idea of relief and the larger concepts of…how to build infrastructure and community,” she added, “are really complicated and challenging.” A true practice of mutual aid is difficult to achieve, said Bank-Muñoz, particularly in a city riven with inequality and with this scale of unmet need. It’s also hard, she added, “to build a long-term relationship when most people are only going to be able to go sporadically.” But while these issues need thought and discussion, she concluded, some things are clear: “People need mold out of their homes.” She was glad to help.

CUNY Connection

Student Union members said that the austerity policies and privatization that make recovery hard for Sandy survivors are also hitting CUNY. “It’s important [that] we, especially members of a public educational institution, show support to the greater community,” Francis-Snyder said. Students, faculty and staff have asked the public to support them in their fights against budget cuts in the past, so giving back through Sandy recovery is another kind of mutual aid. “Brooklyn College students, faculty and staff come from different boroughs, and it’s important to show that we care and are really willing to be part of the solution,” she said.

For faculty members, dealing with the impact of the storm has been part of their daily teaching practice, and made them feel that they had to do more to help. “Brooklyn College students themselves are in crisis,” Bank-Muñoz explained. “I’m dealing with students who have lost homes, have lost cars, can’t get to class, have jobs that have burned to the ground.”

Molina agreed: “I have a few students who were so highly impacted by the storm that it’s like night and day, our experiences are still night and day. Seeing my students go through certain things and hearing their stories made me feel that I have to get out there and see for myself.”

For everyone involved, the day reconfirmed their commitment to continue to be part of the recovery effort. On the trip back, the students and faculty, exhausted and covered in Drywall dust, discussed ideas for fundraising for other caravans, talked about what they learned from working on the flooded homes, and made plans for future organizing campaigns.

For Bank-Muñoz, being part of the recovery effort beyond Brooklyn College campus is part of a broader social movement practice: “What draws me to it is struggle, the capacity for struggle to change the world.”

______________________________

RELATED COVERAGE: