|

Fifty years ago City College Student Government President John Zippert received a Western Union telegram from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., asking him – and other student body presidents – to make their own “personal witness” in support of voting rights and “join me in the march to Alabama’s Capitol.”

Zippert had joined civil rights protests in New York, picketing a Woolworth’s in support of Southern lunch-counter sit-ins and protesting at the 1964 World’s Fair against the lack of hiring of black workers. But this was different.

Two efforts to march from Selma to Montgomery had been turned back, by brutal violence or the threat of it. In the past month a local civil rights activist and an out-of-town supporter, one black and one white, had lost their lives in Selma. But Zippert made the decision to go.

|

Going South

“I had a feeling at the time that the march would be a historic moment, but I didn’t know how historic it would become,” Zippert told Clarion in 2015. “It seemed from the TV coverage that it was a turning point,” he said, “and I felt the more people who went, the more support it would show.”

Zippert and two other City College students left New York together, and another 40 CCNY students made the journey to Alabama three or four days later. They paid the $40 round-trip fares and took packed buses that left at night from Port Authority.

Baruch College journalism professor Josh Mills, then a City College student, was one of those students who made the trip. A native New Yorker, Mills has vivid memories of the first lengthy stop that their bus made, in Richmond, Virginia.

“There were segregated water fountains and segregated bathrooms. And it was like, ‘Woah, we’ve heard of this – but here we are about an hour from the nation’s capital and seeing a water fountain that said whites only,” Mills told Clarion. “It was kind of stunning.”

The students would join the final leg of what would become the last of three efforts to march from Selma to Montgomery, and the first one to reach the capital. The marches were pivotal in the passage of the Voting Rights Act that summer. The first, on March 7, 1965, became known as Bloody Sunday: state troopers and white racists tear-gassed and savagely beat nonviolent protesters as they sought to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge (named after a Confederate general who became a Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan).

At the second march, two days later, activists returned to the bridge, but did not advance past the heavily armed state troopers massed on the other side. That night Unitarian Universalist minister James Reeb, who had come from Boston to take part in the march, was attacked by segregationists and died a few days later.

Civil rights leaders secured federal protection of their third march, a 50-mile trek that went through open farmland, residential neighborhoods and business districts. A federal court order both backed and restricted the march this time: President Lyndon Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard and vowed to send whatever federal forces the defense secretary deemed necessary. But the terms of the court order limited the size of the march to no more than 300 people along the two-lane highway to Montgomery.

“We marched out of Selma on Sunday,” Zippert recalled. “We returned to Selma on Sunday evening because only 300 selected people were allowed to march the full distance….I spent the next few days in Selma working at the SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] Freedom House and helping to mimeograph leaflets.” Zippert then got a ride on the back of a truck and rejoined the march in its final day, as 25,000 people marched into Montgomery to demand voting rights for all.

Documenting the March

The City College students who went were social activists. Some, like Josh Mills, were on the staff of the college’s more left-leaning student paper, Observation Post. In its pages, they shared their experiences of marching with nuns and African-American residents from Marion, Alabama, of hearing “Dixie” blasting from a nearby appliance store, and listening to an old woman proudly sing from her front porch, “This little light of mine.”

|

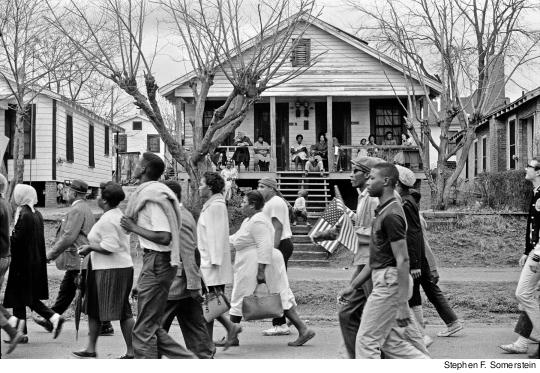

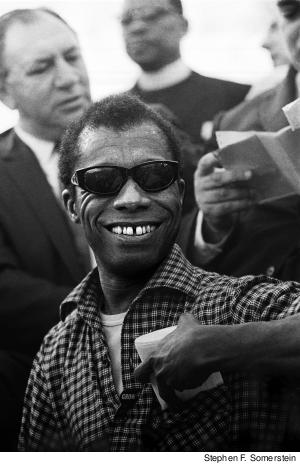

Stephen Somerstein, who attended City College at night and was managing editor of the evening school paper, Main Events, documented the last day of the march in photos. Many of those photos are currently on display at the New York Historical Society in an exhibit titled “Freedom Journey 1965: Photographs of the Selma to Montgomery March,” which runs until June 9. Somerstein took five cameras and about a dozen rolls of film. With a limited amount of film, he knew that each photo had to tell a story; he says he decided early on that he wanted to document what the march meant for African Americans living in Alabama.

“I wanted to capture that sense of hope and reality, the joy and anticipation and thoughtfulness,” Somerstein told Clarion. “There was a certain amount of joy among the younger people. The older people were very serious. It was not a picnic. It was a serious statement that they were making.”

At the Capitol

In one of Somerstein’s photos there’s a multi-generational black family sitting in front of Coke billboard watching the procession. In another photo, the march turns a corner with its destination in view: the white Alabama State House with a Confederate flag flying above it. At the Capitol, Somerstein stepped onstage while Dr. King delivered his “How Long? Not Long” speech.

Somerstein says he didn’t want to take King’s photo from down in the crowd: “I saw there was no one to the back of King. I slid over, found a spot and took three shots” from different angles.” One of the resulting pictures is instantly familiar today: it shows the back of King’s head with the sea of the crowd stretching away in the background. An image from this perspective was adapted for the poster for the movie Selma.

Somerstein’s photos were published in a special civil rights issue of Main Events. Other CCNY students who went to Alabama also wrote accounts of their trip.

Racial Justice on Campus

“I’m back in New York now, safe and secure, and removed from the terror that is Alabama,” wrote City College student Mickey Friedman in an article published in the March 31, 1965 edition of the Observation Post. “I endured Alabama for a day, [Alabamians] must endure it for a lifetime. The heroes of the march were the Alabamians – for their sacrifice is the greatest.”

City College was a politically active campus at the time, with students who ranged across the political spectrum from Young Republicans to Maoists. “Free tuition, civil rights and the peace movement were the big issues on campus,” recalled Vivian Kahn, City College ’65 and former Observation Post editor. The largest crowds turned out for protests in defense of free tuition, in response to Governor Rockefeller’s support for a measure to start charging tuition at CCNY (a stance that, according to The New York Times, led the college’s president to resign in protest). Pro-civil rights activity had a strong presence at CCNY throughout the early-to-mid 1960s: John Lewis and Malcolm X spoke at the campus, while students picketed Woolworth’s and took part in the March on Washington. When the march from Selma arrived in Montgomery, 200 City College students joined in a solidarity march in Harlem.

But questions of racial justice did not only exist in the Deep South. A February 1965 editorial in the Amsterdam News charged that City College of New York was “almost as lily white during the day as the campus of the University of Mississippi.” The daytime student body in the mid-1960s was overwhelmingly white, and most students accepted that state of affairs.

“We were quick to jump on the bus to go to Selma,” former City College student Ron McGuire told Clarion. McGuire had marched in Montgomery, and later as a civil rights lawyer went on to represent many CUNY student activists. “But we were reluctant to bring black students to our college.”

While no official statistics by race were taken by City College at the time, according to York College associate professor Conrad Dyer around 1% of City College’s graduates from 1960-1965 were black. The student body in the evening school, according to estimates by school officials cited in Dyer’s thesis, was almost one-third black, but the number of night students was much smaller.

The lopsidedly white enrollment in a school in the middle of Harlem troubled Allen Ballard, one of the few African-American faculty members at City College at the time. “The contradiction was just too intense in the midst of the whole revolution that was taking place in the country,” Ballard later recalled. In his memoir, Breaching Jericho’s Walls, Ballard wrote that “Black authors such as John Killens, James Baldwin and John Williams…frequently referred to the white citadel on the hill, inaccessible to the black population in whose midst it stood and whose taxes paid for the education of white students and the salaries of white faculty and administrators.”

Precursor to Seek

A proposal from Ballard “to admit a selected number of black and Hispanic students to CCNY” with increased academic support led to the establishment in 1965, the year of the Selma marches, of a precursor to the SEEK opportunity program that exists at CUNY senior colleges today. It was just a start, but it was perhaps the first time that racial inequities in admissions became an institutional concern at City College.

The demands for change that were gathering strength in the mid-1960s led to dramatic changes in direction, for both individuals and institutions.

John Zippert, the student body president who went down to Selma, wrote in the pages of the Observation Post about feeling he was at a crossroads: should he “go South tomorrow,” “organize a group of students to go South this summer,” or “[work] harder here at home in Harlem”? Certainly there was work to do in Harlem, including at City College. Within four years, black and Puerto Rican students were leading an occupation of the campus, which they renamed “the University of Harlem,” and waging a student strike to demand open admissions.

Changing Course

Zippert ended up going back to the South that summer in 1965, where he joined a Congress of Racial Equality organizing project and worked with black farmers on marketing their sweet potatoes. When September came, he stayed.

“It’s been a long summer,” Zippert told Clarion in March of this year. Today he lives in Alabama and still works with low- and moderate-income farmers at the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, which grew out of the civil rights movement. “I went there for the summer, and it really led to the next 50 years of my life.”

For City College, the changes that began in the mid-1960s would prove to be just as profound.