Aaron Swartz was a programmer, a founder of Reddit and an early designer of the technology behind subscriptions to blogs and podcasts. Aaron Swartz was a hacker and an Internet activist, an architect of the Creative Commons system for sharing access to creative work, and a leader in defeating the Stop Online Piracy Act and its carte blanche for corporate and government censorship online. Aaron Swartz committed suicide on January 11 of this year, and his work and his death should give everyone in academia reason to pause and reflect.

Thanks to an over-zealous federal prosecution, at the time of his death Swartz was facing charges with a possible 35 years in prison and a million dollars in fines. His supposed crime? Downloading millions of academic articles from the JSTOR repository with the intent to make them freely available on the Internet. (JSTOR provides online access, for a fee, to more than 1,000 journals.)

Swartz’s ‘Crime’

Swartz’s mass download from JSTOR was reminiscent of his 2008 “attack” on PACER, an online system that charges a fee for access to public court documents created at public expense. As his friend Cory Doctorow recalled, with the aid of software that “allowed its users to put any case law they paid for into a free/public repository,” Swartz “spent a small fortune fetching a titanic amount of data and putting it into the public domain.” For this he was investigated and harassed by the FBI, but never charged.

In the JSTOR case, there was at least one crucial difference: Swartz never disseminated any of the downloaded articles. For this and many other reasons, it’s not at all clear that Swartz’s downloading constituted a crime. There was no evidence his downloads caused physical harm to MIT’s very open network or any economic harm to JSTOR – and JSTOR itself declined to press charges.

To their eternal shame, MIT involved the federal authorities and never asked them to back off. MIT “could have stopped this [prosecution] cold in its tracks by saying they were not the victims of a crime, and they didn’t do that,” Swartz’s partner, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, told the Los Angeles Times.

“The government used the same laws intended to go after digital bank robbers to go after this 26-year-old genius,” said Chris Soghoian, a technology analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union. But in fact, Soghoian said, stealing millions of dollars via computer is not the same as sharing an academic article with the public – even if the latter may violate a website’s terms of service. Legislation proposed by Rep. Zoe Lofgren, days after Swartz’s death, would revise federal law to recognize that distinction.

To put the absurdity and immorality of Swartz’s prosecution into perspective, consider the case of HSBC. Despite the fact that this bank admitted to laundering billions of dollars for Colombian and Mexican drug cartels, violating the Bank Secrecy Act and the Trading with the Enemy Act, the Justice Department pursued no criminal prosecutions. Rather than insisting that bankers go to jail, the government settled for a $1.9 billion fine – five weeks of income for HSBC.

The prosecution of Swartz and his tragic death highlight the skewed priorities of our justice system and the pernicious effects of copyright regimes run amuck. For those of us who work in academia, it obliges us to consider the scandalous state of academic publishing.

Most research monographs and journal subscriptions are expensive; and rare is the academic who does not find that the hunt for a journal article online is blocked by a paywall. Though we inhabit a world in which the distribution and dissemination of information is easier by the day, some very old stumbling blocks remain.

Why is this archaic system of production and distribution still dominant? How does it work? It works because academics, ironically enough, underwrite it with our unpaid labor. We conspire to make things harder for ourselves in ways that are damaging to our universities. It works because academics collaborate with a system whose incentives and interests are not aligned with our own.

Consider, as an example, Elsevier, a publishing house known for “premier” journals like Cell and The Lancet. It is able to sell those journals at high prices because they include results of research conducted by university academics the world over, much of which is publicly funded. Elsevier does not pay for the research, it does not pay for the papers to be written. The editorial boards of Elsevier journals are staffed by unpaid academics, who then ask other academics to serve as unpaid reviewers. By “unpaid,” I mean of course that faculty are not compensated by Elsevier for their work on its journals – but this work also gets little or no recognition in academic workloads. (It is only tangentially acknowledged by promotion and tenure boards.)

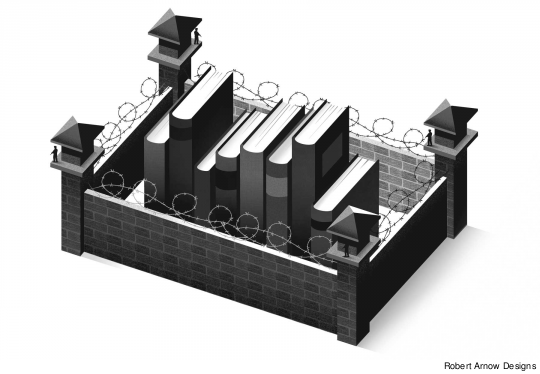

Paywalls

Once a research paper is accepted for publication, it is sent back to the author – who typesets it (using perhaps a style sheet provided by the publisher), prepares a camera-ready copy and sends it back for publishing. In return for this uncompensated labor, the publishing house makes authors sign forms handing over copyright, then prints the article in a journal that it sells for thousands of dollars per year to the very universities where its authors, reviewers and editors do their work. In effect, Elsevier sells academics’ unpaid work back to them, at an increasingly unaffordable cost.

Once published, the material is not open-access anymore; it is closed behind a paywall. If your library, at say, an underfunded public university like the City University of New York, is experiencing budget problems, you may be out of luck. If you are a taxpayer who funded this research, but don’t have access to a journal’s subscription, you are out of luck again.

Here’s what happened to Jonathan Eisen, an evolutionary biologist whose brother is a co-founder of Public Library of Science (PLOS), a prominent open-access scholarly journal: “Even with my brother starting PLOS…I didn’t understand why this was a big deal. And then we had a family medical emergency, and I was up at 3:00 [am]…next to my wife in the hospital room, surfing the web…trying to find information about a particular medical treatment. And I couldn’t get access to the damned papers!”

Eisen stresses that he is not a utopian: “Nobody is saying that publishing is free. What people are saying is that…taxpayers and the government are [already] paying for this. So why can’t we do it in a way where the knowledge is distributed broadly, as opposed to where the knowledge is restricted?”

Some open-access journals post any paper that meets very basic quality standards, relying on new forms of online peer review to identify the most important work. Others have editorial boards that serve as more restrictive gatekeepers, deciding what is worth publication. What all open-access journals have in common is that they do not charge for access to knowledge.

What can academics do to support this kind of change? Most straightforwardly, they can start by refusing to support the current system. On January 21, 2012, mathematician Timothy Gowers of Cambridge announced he would no longer publish in Elsevier’s journals or serve as an Elsevier editor or referee. This boycott has now been joined by thousands of other academics. (I don’t referee any more for Elsevier, though I have in the past, and I won’t send any papers to its journals.) Thanks to the furor created by three Fields Medal winners – Gowers, Terence Tao and Wendelin Werner – participating in the boycott, many are increasingly aware that academic publishing is a racket that relies on self-exploitation. Bear in mind that in 2010, Elsevier reported a 36% profit on revenues of $3.2 billion.

Not every publisher is an Elsevier. But others come close, and for-profit, closed-access publishers are all using the same dysfunctional model.

To disrupt this system requires work. The overarching problem is that in the academic world, traditional printing presses still command the greatest power and prestige. Online publication counts for little in institutional decisions, even as it increasingly becomes a forum for cutting-edge scholarship, even when PLOS is cited on the front page of The New York Times as routinely if it were Nature. The dissemination of research is changing, but the tenure and promotion process within universities is not. And unfortunately, so long as university promotion and tenure boards refuse to give due weight to open-access publication, academics will hesitate to publish in those forums – and this will act as a serious drag on the speed of change. As long as Elsevier, and closed-access presses like it, are seen as publishing the “prestigious” journals, the ones academics really want to be published in, the current dysfunctional system will hang on.

So, university promotion and tenure boards need to pay closer attention to open-access journals and presses. They need to acknowledge the new models for academic publishing and peer review now exist, and must be taken seriously. University administrations must act to bring academic publishing back within the control of the academy. Modern publishing’s production requirements can be financed by a consortium model, which would fund the work that professors and graduate students do on the editing, review and distribution of journal papers and research monographs. The work they do on these publications should be counted as part of their workload and should be reckoned with in their promotion and tenure decisions. Universities can provide institutional backing for open-access publication fees – and many already do.

But most pressingly, senior academics, especially those with full professorships and tenure, need to take the lead. The academy runs on the Matthew Principle: those that have, get more. If this present situation is to change, those that have the most need to give away the most. They need to lend their reputation and prestige to open-access journals and presses so that the profile of those journals can be raised, and articles they publish will start to receive appropriate weight in career decisions.

Moving Prestige

Change will come when those who have sufficient power, those who can easily get their fifth book published again by Cambridge University Press, will finally say, “I choose to make my book open-access and make it available online.”

Senior academics need to follow the call of Harvard’s Faculty Advisory Council, and “move prestige to open access.” This is a reputation economy, and those that are wealthy need to spread the joy, as it were. It is impractical to expect junior academics to take the lead in this regard.

Other reforms are possible: all federally funded research, not just some, should be subject to an open-access requirement; copyright law should be amended for academic research; and so on. But first and foremost, the university must reform itself. Stop collaborating with the traditional model, and by using and promoting open-access models of publishing, help them to become the norm.

______________________________

Samir Chopra is an associate professor at Brooklyn College. He studies the relationships between law, technology & philosophy.

What do you think about open access and the future of academic publishing? Clarion would like to hear your views. Send letters to the editor or proposals for op-ed articles to our editor, at [email protected].