SUNY Buffalo shut down its Shale Resources and Society Institute (SRSI) late last fall, after months of controversy over the Institute’s relationship to the gas and oil industry. “Research of such considerable societal importance cannot be effectively conducted with a cloud of uncertainty over its work,” wrote University President Satish Tripathi in a November 19 statement. It was the culmination of a dispute that raised questions about corporate influence on academic research in an era of deep cuts in state support for public higher education.

“The Institute was promoting itself as an independent, non-biased scholarly project, but it was acting as something entirely different,” said Martha McCluskey, a SUNY Buffalo law professor and a member of the UB Faculty Senate’s executive committee during 2011-2012.

|

The controversy unfolded against the backdrop of a nationwide boom in natural gas production, thanks to a new technique known as high-volume horizontal hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” Drillers inject millions of gallons of water, sand and an array of chemicals thousands of feet into the earth to unlock previously unreachable gas reserves. The fracking boom has been accompanied by growing concerns about its impact on underground water supplies and the health of impacted communities. While the chemicals used in fracking include a number of carcinogens, their exact composition has never been made public, thanks to an exemption to the Clean Water Act approved by Congress in 2005 at the urging of former Vice President Dick Cheney.

Fierce Debate

The debate over fracking has become especially fierce in New York, where trillions of cubic feet of natural gas are estimated to lie beneath the central and southern parts of the state in a geological formation known as the Marcellus Shale. This includes areas from which New York City obtains most of its fresh water supply. A moratorium on fracking is currently in force in New York State. Citing prospects for economic growth, supporters of the oil and gas industry are eager to see Governor Andrew Cuomo overturn this drilling ban, while many fracking critics would like to see it made permanent. Cuomo is expected to announce his position in mid- to late February.

In the spring of 2011, with debate on the issue heating up, SUNY Buffalo hosted an eight-part lecture series on fracking. It received $12,900 in sponsorships from the gas and oil industry and exclusively featured pro-fracking speakers.

Marcus Bursik, professor of geology and a former department chair, defended the lecture series. “The seminar series was mostly started…to give necessary information to geology students about how the oil and gas industry works,” Bursik told Clarion. He said about half of SUNY Buffalo’s geology majors go on to work in the oil and gas industry, while the other half go into environmental consulting.

Absence of industry critics from the series was not a problem, Bursik said: “If I teach a class in aeronautics…does that mean I am obliged to teach a class in how not to fly?”

The lecture series did not acknowledge its sponsors, noted Jim Holstun, a professor of English at SUNY Buffalo. “I had never seen anything like it,” he told Clarion.

The Shale Resources and Society Institute was launched in April of the following year. One of its two co-directors was Robert Jacobi, a professor of geology at SUNY Buffalo who is employed by the natural gas company EQT as its senior geology advisor. Last year EQT drilled 127 new wells in the Marcellus Shale areas of Pennsylvania and West Virginia; in 2013 it plans to drill 153 more.

The other co-director was consultant John Martin, a former New York state energy official, who was hired at $72,000 per year for a quarter-time schedule. His company, JPMartin Energy Strategy LLC, describes itself as providing “strategic planning [and] government/public relations services to the energy industry.”

McCluskey told Clarion that when the SUNY Buffalo administration established the Shale Institute, it circumvented the committee process in the College of Arts and Sciences as well as the Faculty Senate. “At every turn, it developed outside of the normal channels expected by faculty,” McCluskey said.

The Shale Institute’s first report, released on May 15, asserted that state regulations in Pennsylvania had made fracking less risky. The report contended that strict regulation in New York would protect local residents from any dangers posed by fracking. SUNY Buffalo sent out a widely circulated press release featuring the institute’s conclusions.

But later in May, the Buffalo-based Public Accountability Initiative (PAI) issued a critique of the Shale Institute report. Among PAI’s findings:

• While the report claimed that between 2008 and 2011 Pennsylvania had lowered the odds of major environmental impacts from fracking, its own data tables showed that the opposite is true. “The rate of incidence of major environmental events actually increased from 2008 to 2011, from 0.59%, or 5.9 per 1000 wells, to 0.8%, or 8 per 1000 wells,” concluded PAI.

• All four of the co-authors of the Shale Institute report had financial ties to the natural gas industry. Parts of the Shale Institute report were lifted almost word-for-word from an explicitly pro-fracking report issued by the right-wing Manhattan Institute in 2011. That report was written by three of the co-authors of the SRSI report.

• The original press release for the report stated that it had been peer-reviewed, a claim that was later retracted.

“It was an incredibly shoddy piece of work,” Holstun said of the Shale Institute report. “It makes eighth-grade arithmetic errors.”

Bursik told Clarion that criticisms of the report’s errors were overblown. “People make mistakes all the time in the sciences,” he said.

On the erroneous claim that the report has been peer-reviewed, Bursik said, this “wasn’t anything sinister.” Co-director John Martin, he explained, thought that running his work by trusted friends and colleagues was the same as peer review. Noting that Martin has a PhD in urban and environmental studies, Bursik asked, “Who could have predicted that he wouldn’t know what peer review means?”

Ronald Bishop, a lecturer in chemistry and biochemistry at SUNY Oneonta, told Clarion that Pennsylvania has failed to protect its residents from fracking’s negative effects. Bishop said that people living near these wells have experienced rashes from exposure to warm water while washing dishes or taking a shower, as well as increases in respiratory and pulmonary ailments from airborne particulates. Increases in some chronic diseases may not appear for another 15 to 20 years, Bishop said.

In June, SUNY Buffalo officials said that critics of the Shale Institute were trying to “dictate the position taken by…faculty members,” a charge Holstun rejects. “Academic freedom doesn’t mean imperviousness to debate or to correction of mistakes,” he said.

The SUNY Buffalo administration has denied that money from the natural gas industry funded the Shale Institute. But in the press release that announced the Institute’s formation, co-director John Martin states that the Shale Institute “plans to seek funding from sources including industry and individuals.” Minutes of a May 15 meeting discussing Institute fundraising noted that “funding is still slow and sponsors have not committed yet.”

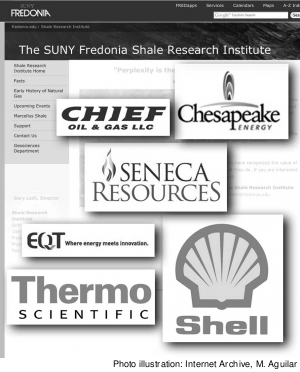

A smaller Shale Research Institute at SUNY Fredonia, established three years earlier, received funding from a half-dozen companies in the oil and gas industry, and it featured their logos on the “Support” page of its website (see image above). “When a corporation gives you a gift, you want to say thank you,” a SUNY Fredonia spokesperson explained to The New York Times in June.

Business Council

The Business Council of New York State had welcomed the founding of the SUNY Fredonia institute in 2009: “This type of academic and industry partnership…can balance the often inaccurate and outdated information that opponents of development feed to the media,” wrote Business Council blogger Jennifer Levine.

A SUNY Fredonia spokesperson told the Buffalo weekly Artvoice that all funding for its Shale Research Institute was channeled through the private Fredonia College Foundation. Critics of SUNY Buffalo’s Shale Resources and Society Institute suspect that it may have similarly received industry donations routed through the University of Buffalo Foundation, which was covering John Martin’s salary as Shale Institute co-director. The privately run UB Foundation has a $736.3 million endowment, by far the largest of any SUNY school, which Holstun refers to as a “secret pot of money that can be used for laundering corporate contributions.” Officially private-sector entities, the UB Foundation and the Fredonia College Foundation are both exempt from New York’s Freedom of Information Law (FOIL). Proposals to extend FOIL to cover college foundations have stalled in the State Legislature in recent years.

UB Clear

As criticism of SUNY Buffalo’s Shale Institute mounted, a group of faculty, students and community allies founded the University of Buffalo Coalition for Leading Ethically in Academic Research (UB CLEAR) to rally opposition to the Institute. “It has damaged UB’s hard-won reputation and credibility as a major research university,” the group said in a June 2012 press release. That same month, after the Times article appeared, the website of SUNY Fredonia’s Shale Research Institute went offline.

Over the summer, UB CLEAR led a campaign to pressure the SUNY Board of Trustees to intervene, sponsoring a faculty petition that called for greater transparency in the Shale Institute’s operations. Meanwhile the Shale Institute controversy was gaining national attention: an online petition campaign by CREDO Action garnered more than 11,000 signatures calling for the Buffalo institute to be shut down.

On September 12, the SUNY Board unanimously passed a resolution calling on SUNY Buffalo to explain the Shale Institute’s origins and the role of natural gas companies in its workings. The Buffalo administration responded with a 162-page reply defending its past actions, but the controversy refused to die down.

Seven weeks later, SUNY Buffalo finally changed course, and the Shale Resources and Society Institute closed its doors. Its smaller predecessor at SUNY Fredonia is apparently out of business as well: in January 2013, a Fredonia spokesperson told Clarion that its Shale Research Institute has gone “on hiatus,” with no plans to reopen.

“This is an important chapter in a much larger fight for academic integrity and transparency,” the Public Accountability Initiative declared after SUNY Buffalo’s decision was announced, and SUNY Buffalo professor Martha McCluskey agreed.

“If we don’t maintain our academic core and purpose, what’s the point?” she told Clarion. “Industry can pay for its own public relations.”