Larissa Swedell, left, and Michael Newman initiated a department chair letter against the CUNY directives. (Credit: Erik McGregor)

The directives from CUNY Central were sudden, extreme and would hurt CUNY workers across titles. In early February, Central administration announced a hiring freeze, cuts to college budgets by 5 to 7% and the reestablishment of a CUNY Central Vacancy Review Board (VRB) to oversee almost all hiring decisions. The administration also singled out adjunct budgets for the chopping block.

Department chairs across CUNY organized. Many PSC members gave powerful accounts at a March 20 Board of Trustees (BOT) meeting on how the looming cuts would affect their campuses. “The savings plans and VRB are destabilizing and disrespectful. They should not be implemented,” PSC President James Davis told the CUNY Board. “They should not have been announced to begin with, because the message they send is that CUNY can absorb additional cuts. We cannot.”

SOME CHANGES

Two days after those testimonies, CUNY administration partially reversed course. On March 22, Chancellor Félix Matos Rodríguez sent a letter to college presidents and deans, saying that the CUNY Central VRB will not be required to review “budget neutral” or “cost savings” positions, which would instead be subject to an internal college process, including approval by a college-level VRB. In short, Central would refrain from interfering in searches already authorized by colleges that did not add to the college’s budget. Hires that result in a cost increase would still require Central approval.

The backpedaling was the result of union organizing and department chair pressure around Central administration’s overreach in college and departmental matters. And while the union considers that a victory, it continues to pressure the administration to withdraw the savings plans that were drafted by colleges and suspend all VRBs. To add your name to that letter, go to tinyurl.com/against-CUNY-cuts-letter.

“CUNY colleges have lost hundreds of full-time faculty and staff in recent years. Our students do not have the support they need, and the remaining workforce is overstretched in every direction. Unmet needs abound,” states the union letter to Matos Rodríguez and CUNY BOT Chair Bill Thompson. “Our students deserve greater investment, not accommodation to austerity.”

DEPARTMENT CHAIR LETTER

A March 12 letter signed by 110 department chairs across CUNY protested the measures “undermining the search process” and “micromanaging the hiring process.” The letter was sent to Matos Rodríguez, Thompson and BOT Vice Chair Sandra Wilkin. By April, 170 department chairs, more than a third of all the department chairs at CUNY, had signed the letter.

“It came out of outrage and frustration,” said Michael Newman, a professor and chair of linguistics and communications disorders at Queens College and one of the chairs who drafted the statement. Newman objected to the suddenness of the cuts and CUNY Central’s micromanagement from afar. “They were deciding for our college what areas they needed to cut, which hires were not going to go through, after they had authorized all these hires. They suddenly took over as if the colleges were incompetent to make cuts on their own.”

Department chairs noted that vital, hard-won positions were now in limbo, at a time when there is nothing left to cut in their departments. They wondered if CUNY Central was also subject to cuts.

“They’re basically running out the clock on searches that are underway and guaranteeing that they are failing,” said Larissa Swedell, professor and chair of anthropology at Queens College, who co-drafted the statement with Newman. “[For] searches [that] are at the end of the process, they’ve already had their interviews, they’ve chosen a candidate and they’re not allowed to make an offer because they’re waiting for two to four weeks for VRB approval,” said Newman.

While more local control in hiring matters is welcome, the budget cuts and hiring freeze still stand. And they are significant. Hector Batista, CUNY’s executive vice chancellor and chief operating officer, announced the cuts in a February 3 memo to college presidents and deans, giving colleges six weeks to come up with a savings plan for fiscal year 2024 (from July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2024).

In short: more cuts on top of cuts already required in fiscal year 2023. Batista didn’t offer a reason for the increased squeeze. However, he stated that CUNY will be monitoring enrollment data and funding from the state and city. A union analysis of CUNY data shows that enrollment is down CUNY-wide by around 20% from Fall 2018 to Fall 2022. Batista directed one specific area to cut: adjunct budgets.

“[Do] an in-depth analysis of adjunct costs considering the University’s declining enrollment and hiring of 595 new full-time faculty by the Fall 2023 semester,” stated the memo.

Lynne Turner, PSC vice president for part-time personnel. (Credit: Erik McGregor)

ADJUNCT CUTS

Adjuncts across CUNY are fearing for their jobs. At some campuses, there were rumors of limiting adjuncts on three-year appointments, a contractual provision won by the union in 2016. The union is organizing against this prospect and to resist any of these job cuts or layoffs. Appointment letters come on or before May 15.

“Batista’s memo places a bull’s-eye directly upon the livelihoods of the more than 13,000 part-time faculty and staff that our union represents,” said Lynne Turner, the PSC vice president of part-time personnel. “These austerity cuts will, if implemented, deepen the vicious cycle of layoffs, under-enrollment, class cancellations, larger class sizes and further cuts and job loss with dire consequences for CUNY students and all our members.”

The irony of these cuts was not lost on members. Some of CUNY’s most vulnerable and lowest-paid workers were facing the threat of job loss, while Hector Batista, the CUNY administrator who wrote the memo, received a 27% pay increase to his salary late last year, from $330,000 to $420,000; a raise that goes retroactive to December 31, 2021. Batista “also gets a car and is driven by various university peace officers,” an insider told the New York Post.

JOB SECURITY

While top-level administrators secured exorbitant raises, the future of many adjuncts remains unknown. At Bronx Community College (BCC) there have been some efforts for shared governance around the cuts, but it’s unknown how the cuts will play out, said Kathleen Urda, who serves as co-chair of the Council of Chairs at BCC.

CUNY’s cuts undermine recruitment efforts. (Credit: Ari Paul)

“I feel like I’m in limbo right now, and there is anxiety and low morale on campus because it’s unclear what the upshot will be,” said Urda, a professor and chair of the English language and literature department. “I have faculty asking me whether they’re going to be hired back, and I have to say, ‘I really don’t know right now.’”

Holly Clarke, a long-serving adjunct in the public management department at John Jay College, testified to the BOT that she’s afraid of losing her job. She’s been teaching at the college since the late 1980s.

“Many of the adjunct faculty, who will lose courses and income or be laid off altogether, (likely 500 to 1,000 faculty), have taught for years in their departments. They have experience with our CUNY students and often teach introductory and lower-level courses, courses that are key to student retention,” Clarke, an adjunct lecturer, told the BOT. “They are not disposable or easily replaceable.”

In mid-April, PSC President James Davis sent guidance to all CUNY department chairs on the directive to cut the adjunct budgets, saying that adjuncts should not be treated as “interchangeable” and “disposable.”

“The entire adjunct budget of all the colleges combined is only 8.2% of CUNY’s $4+ billion total operating budget. There are other ways to meet the current fiscal challenges without harming faculty members or impairing the student experience,” Davis said.

He outlined a list of recommended priorities to department chairs, including avoiding assigning teaching overloads to full-time faculty members; reappointing adjuncts currently on three-year contracts; appointing adjuncts eligible for three-year appointments who have been reviewed satisfactorily, along with adjuncts who rely on CUNY for their health insurance; communicating with other departments and programs across the university to help find positions for adjuncts they are not able to appoint; and convening discussions with full-time faculty to see if they’re willing to teach an underload that can be made up later.

VACANCY REVIEW BOARDS

The union also plans to turn out members to the May 8 BOT hearing in Queens to protest the cuts, especially at the adjunct level. (See page 12 for details.)

The CUNY Central plan still requires the colleges to vet revenue-neutral positions with their own newly created VRBs. Most of the boards at CUNY campuses consist of only CUNY administration, but at Brooklyn College (BC) there are faculty and staff on the local VRB. Carolina Bank Muñoz, the PSC chapter chair for Brooklyn College, is one of the five voting members on the board. It’s thanks to the BC chapter’s persistent organizing work that they have a seat at the table.

Carolina Bank Muñoz, PSC chapter chair at Brooklyn College (Credit: Dave Sanders)

With the latest directive from Matos Rodríguez, it’s unclear how it will play out on the campus level because in order to establish something as “revenue neutral” or “cost savings,” it needs to align with the college’s proposed budget cuts submitted to CUNY Central, Bank Muñoz said. At the latest BC VRB at the end of March, 16 positions were approved, and half of those positions could stay at the college level and await final approval. By the end of March, the BC VRB approved around 50 positions, and fewer than 10 have been officially approved.

Bank Muñoz told Clarion that faculty and staff are very demoralized on campus, and feel they can’t continue to absorb more cuts.

“I want to be clear these are political choices they are making with people’s lives,” Bank Muñoz said.

For instance, short-staffed and relying on college assistants to do the work of HEOs who had left. Now it’s those college assistant positions – and in some cases their extended hours – that are on the chopping block.

“It’s going to lead to speedup, which is already a huge issue on the campus,” she said, referring to the fact that staff will being doing more work in less time.

The Baruch PSC chapter leadership wrote to their president in mid-March, demanding management share the savings plan, open up the campus VRB from being a management-only board and participate in a university-wide town hall on the budget cuts. At this point, there has been no movement from administration on these fronts.

At Hunter, Brooklyn, Borough of Manhattan Community College and perhaps other colleges, administrations are seeking to help achieve their savings targets by increasing revenue, or by addressing what Batista calls in his memo “historically low student collection rates.” One source of revenue at Hunter is the resumption of the practice of sending “delinquent” student accounts to collections.

LOW MORALE

City College of New York (CCNY) faculty who teach four-workload-hour composition courses were informed that beginning in the summer, those courses would be three hours. The English department is pushing back, and the union immediately filed a grievance. The fourth workload hour has been in practice for three decades and it’s similarly used for many CCNY math and science courses. City reported that at City College, “16 adjuncts and six full-time faculty members, all of whom teach composition, held a ‘grade-in,’ sitting in the hallway in front of the dean’s office grading student papers,” along with “the support of close to a dozen undergraduate students.”

At City Tech, where there has been a low HEO-to-student ratio, there is an acute need for more staff, especially in financial aid, billing, registration, counseling and academic advisement.

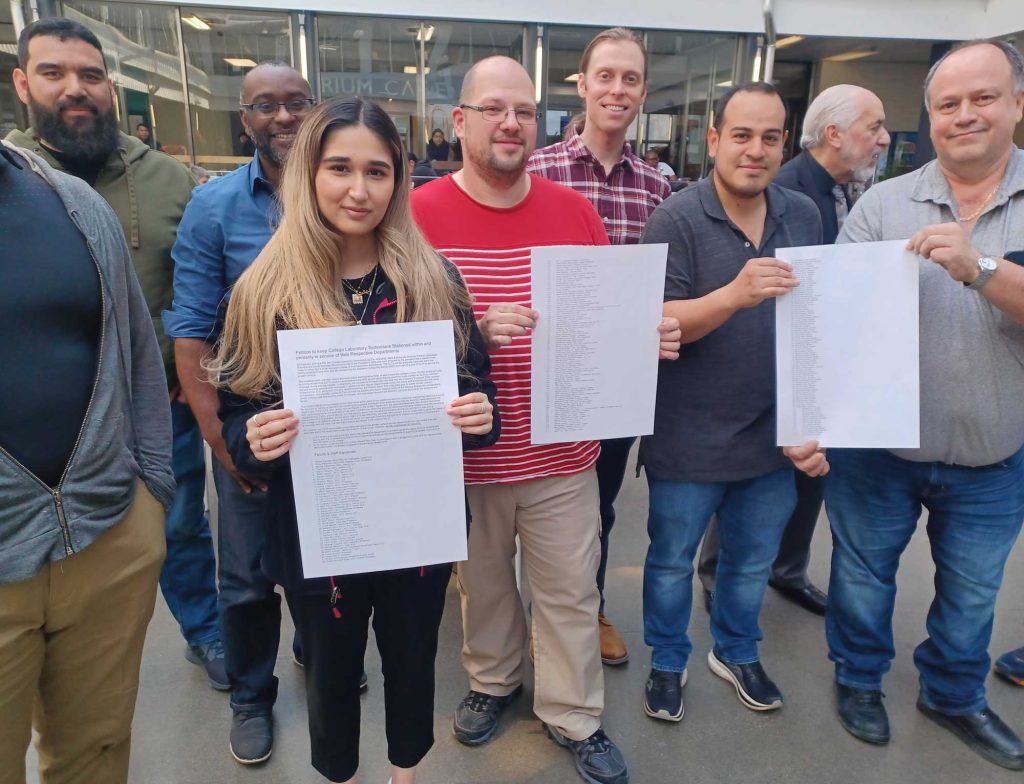

CLTs at Queensborough Community College gathered petition signatures. (Credit: Sam Rasiotis)

“Students struggle to make appointments in counseling or financial aid as those offices are understaffed. Personnel work excessive workloads and hours because someone has left a position and is not replaced. Weary faculty advise randomly assigned students from a wide range of majors with complicated requirements because of a lack of advisors on campus,” Carole Harris, PSC chapter chair at City Tech, told the BOT.

A common theme on all campuses is discontent and overwork, with little sign of shared sacrifice from administration.

“Morale has definitely been impacted. The austerity measures of budget cuts and a hiring freeze make it that much harder for us to do our jobs effectively,” said Carlos Parker, assistant director of admissions at City College. He said now there’s about half the number of full-time staff, as compared to when he started working in the office in 2008. “Members are starting to lose hope for relief, and that’s bad for everyone, our students most of all.”

CLT ISSUES

At Queensborough Community College, adjunct CLTs and nonteaching adjuncts face the threat of non-reappointment, while administration plans to unilaterally relocate eight long-serving CLTs from their home departments to a new technology support and service center housed within the existing academic computing center, where there is a shortage of staff. In April, members presented to their college administration a petition with hundreds of signatures denouncing the move.

“For a long time, CLT staffing levels have been operating at the bone. These recent budget cuts cut into the bone and deep into the marrow,” said Amy Jeu, a cross campus officer on the PSC Executive Council and a CLT at Hunter College. “

Published: April 26, 2023