Issues in retention and recruitment

|

CUNY top officials say that they’re addressing a reported lack of full-time black faculty members across the university. Have they had success? That depends on whom you ask.

At a hearing of the New York City Council’s Higher Education Committee on September 27, lawmakers examined what many believe to be a dearth of full-time black faculty at the university. From CUNY’s perspective – as delivered in testimony from the interim chancellor, Vita Rabinowitz – it has successfully filled half of the campus presidency positions with blacks or Latinos, and professional development programs meant to promote and retain minority faculty members are thriving.

POOR REPRESENTATION

But for the council’s Higher Education Committee members and, indeed, the many full-time CUNY faculty members who testified in September, the numbers tell a much different story. “Though minorities comprised 36 percent of CUNY staff, between Fall 2010 and Fall 2017, the number of black faculty inched from 933 to 941, making up 12.3 percent of CUNY’s workforce. And though 44 percent of the staff hired during the 2016-2017 school year were non-white, just 15 percent were black,” the Chief newspaper reported.

PSC President Barbara Bowen said, “Racial justice is a labor issue, especially in this country. The PSC is firmly committed to increasing the racial and ethnic diversity of the faculty. One of the primary reasons for the difficulty in recruiting and retaining black faculty at CUNY is CUNY’s substandard salaries and inordinately heavy teaching load. When you add those issues to the other, less tangible issues faced disproportionately by black faculty, it is not hard to see why there are fewer black faculty than there should be.” She continued: “CUNY has also lost 4,000 full-time faculty lines since the 1970s. A huge opportunity for hiring a more diverse full-time faculty is being lost – just when the number of people of color earning PhDs has increased.”

She added, “It’s time the City and State woke up to the consequences of their failure to fund CUNY at a level that allows for sufficient numbers of full-time faculty, competitive pay and good working conditions. Any effort to increase the representation of black faculty will be hollow if a job at CUNY still means economic and professional sacrifice, even self-sabotage.”

According to faculty members who addressed the issue at the hearing, the problem is particularly troubling for CUNY, a system that overwhelmingly serves communities of color.

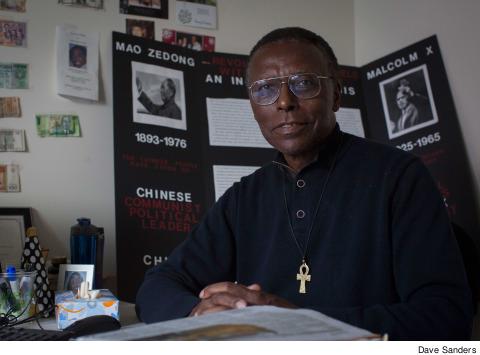

“I am especially pained to see the distressingly low representation at Brooklyn College, where I’ve been teaching since 2009,” said Ron Howell, an associate professor of English at Brooklyn College. “In the English department…I’m the only black male out of almost 40 full-time professors. This is in a borough with 900,000 black residents.”

Worse, a higher education committee report specifically prepared for the hearing noted dismal results from a study across CUNY campuses that examined several equity factors, including a ratio of black students to black faculty: “The College of Staten Island, for instance, received a grade of F for a black-student-to-black-faculty ratio of 94-to-1, while Brooklyn College received a grade of D for its 52-to-1 ratio.” York College, Lehman College and John Jay College received C grades, the report went on to note. Baruch College, City College, Hunter College and Queens College all earned B grades.

“The report cautions, however, that even high grades, such as A’s and B’s, are not necessarily indicators of exceptional performance, but instead are markers of equity between comparison groups,” the city council report said.

One theme faculty members addressed in testimony to the council was that the problem wasn’t solely about the lack of black faculty in general, but also the college administration’s lackluster commitment to hiring full-time faculty members.

“From Fall 2010 to Fall 2016, Baruch College had 119 full-time faculty. Three of them were black (2.5 percent), the lowest number and percentage of black hires of all CUNY colleges,” said Arthur Lewin, a professor of black and Latino studies at Baruch, in his testimony. “Baruch College’s own 2017 Affirmative Action Report admits that, if the college were to rehire proportional to the available pool of candidates, its 505 full-time faculty would have 35 more black professors. In recognition of this dismal fact, the administration, in its 2013 Strategic Diversity Plan, pledged that it would have periodic meetings with black and Latino staff to uncover the problems they face in getting reappointed, tenured and promoted. Five years later, the first such meeting has yet to occur.”

ATTRITION

Lewin added that his own department has been reduced to just three professors and that his college’s administration won’t make new hires to replace the people who leave, something he called the “slow, deliberate destruction of the black and Latino studies department through unaddressed attrition.”

James Blake, the president of the Borough of Manhattan Community College Black Faculty and Staff Association, looked at his campus from a historical perspective in his testimony, noting that when he joined the faculty in the 1970s, it was on the heels of sit-ins and demonstrations by black and Latino students throughout CUNY demanding a more diverse full-time faculty.

He lamented that the more things change, the more things stay the same, saying, “Unfortunately, among the faculty represented at CUNY, diversity remains an issue. I surveyed the academic departments at the college in terms of qualifying the population of black full-time faculty. What I discovered was disturbing. For example: modern language department, 27 full-time faculty, none of them are black; science department, 58 full-time faculty, none of them are black; computer science department, 16 full-time faculty, none of them are black.”

Many of the faculty members who testified noted there was a correlation between the lack of black full-time faculty and what they saw as lack of CUNY’s investment in much-needed departments and programs focused on African American studies. “Although nearly 25 percent of students in CUNY are black, the institutional support for programs reflecting black studies has been reduced over the last three years,” said Brenda Greene, the executive director of the Center for Black Literature at Medgar Evers College. “Colleges have failed to replace faculty who have retired or resigned, thereby affecting program growth and the number of black studies majors.”

Departing faculty have cited a lack of support from the administration as a rationale for resignation. In some colleges, there are no full-time or part-time faculty directly connected to a black studies program. There are also high attrition rates for directors and coordinators of black studies programs. In one college, there have been five coordinators of black studies in 10 years.

And PSC members also recognized that there have been past practices to increase diversity that could shape future policy.

Anthony Browne, chair of the Africana and Puerto Rican/Latino studies department at Hunter College, for example, testified, “Recruitment of black faculty can be a challenge particularly in departments with an uneven history of tenured black faulty. A strategy that has been successfully utilized by both public and private universities to address faculty diversity is cluster hiring. A cluster hire would involve hiring a critical mass of black faculty members based on shared, interdisciplinary research interests. These hires could be in a single department of a cross-disciplinary research area that would provide the new hires with a community of scholars that would reduce feelings of isolation and marginalization.”

TOWARD PROGRESS

And John Gallagher, a higher education officer delegate at Borough of Manhattan Community College, told Clarion, “On the HEO side of the house at BMCC we had a long-tenured vice president who insisted on rigorous affirmative action searches for staff titles. Everyone was hired from a nationally advertised search using a diverse search committee that didn’t include the immediate supervisor. We managed to get an incredibly diverse staff in just about every definable category with great acceptance by the overall community. We regularly met or exceeded our diversity goals, filling well-paid positions with a diverse group of talented, dedicated professionals.”

BEST PRACTICES

Several years ago, in the course of examining the issue of diversity among instructional staff at CUNY, PSC talked at length to several (now former) department chairs of color about their successful practices for achieving diversity among full-time faculty in their departments. These chairs spent a great deal of time ensuring that qualified faculty of color applied and were considered for faculty positions. They also worked with all untenured faculty and faculty interested in promotion to identify opportunities for funding and release time for research and scholarship. Recruitment and retention of faculty of color were successful in these departments.

Bowen added, “The racial composition of the faculty is not only an economic or labor issue; it is an intellectual issue. Whole fields of knowledge have been transformed by the work of black scholars together with the contributions of other faculty of color, working-class faculty and women of all races. Their work has immeasurably expanded what it is possible to know. CUNY students, above all, should be the beneficiaries of – and participants in – this transformation.”