Replacing human workers?

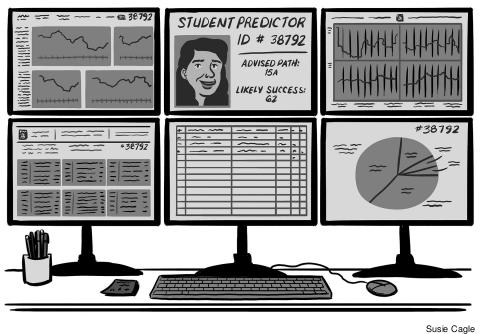

The CUNY Board of Trustees has authorized a five-year contract worth nearly $11 million with EAB (formerly Education Advisory Board) to provide new software for academic advising in CUNYs senior colleges – essentially a computer system that uses an individual student’s data, such as their grades and attendance, as a measurement for their success in higher education. Some education experts worry about the system’s effects, while others question whether the expense is justified when senior colleges are being hit with budget cuts.

DOWN SOUTH

Colleges and universities around the nation are using EAB software. At Georgia State University, which has a student population similar to CUNY’s in some ways (large numbers of low-income students who are the first in their families to attend college), the results have been widely celebrated. The number of degrees granted by GSU increased 30 percent during the first five years of the program. Even more dramatic, the number of black men graduating with STEM degrees went up 111 percent.

But in her 2018 book, Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police and Punish the Poor (St Martin’s Press), Virginia Eubanks shows that while technologies like these are often touted as a way to deliver services to the poor more efficiently, they can worsen economic and social inequality. More data, she argues, can’t substitute for a lack of resources.

In an interview with Clarion about CUNY’s new EAB contract, Eubanks pointed out that there has likely been much more to Georgia State’s success story than predictive analytics. Instead of using algorithms to do more with less, GSU “vastly increased its stock of resources” for academic advising. Inside Higher Ed reports that before the system was introduced, 1,000 meetings between students and academic advisors took place; last year, that number was 52,000. After launching the program in 2012, GSU hired 42 new academic advisors, at a cost of $2.5 million per year.

NEED RESOURCES

In short, Eubanks said, the Georgia State story is “the opposite” of the cases she writes about in her book, as the university was not seeking to use algorithms to deprive people of services, or as a substitute for resources. Rather, GSU is using the technology to answer a question rarely heard at CUNY. As Eubanks put it, “How do we make good use of our vastly expanded resources?”

The lack of resources at CUNY, by contrast, could set this experiment up for failure. Jennifer Harrington, assistant director of academic advisement at Baruch College’s Austin W. Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, points out that CUNY is “constantly crying poverty. They can’t give adjuncts a living wage. They can’t even get the mice out of some of the classrooms.” Harrington points out that most CUNY colleges also need more academic advisors, and questions the administration’s judgment when it comes to investments in technology: “Look at all the money they spent on CUNYfirst, and that doesn’t work very well!”

REMAKING COLLEGE

There are other concerns about using predictive analytics in higher education. Harrington worries that advising-by-algorithm could “take away the serendipity” of the college experience. “Learning from your mistakes, figuring it out as you go along,” she said, “that’s the best of college.”

Worse, as others predict, the numbers won’t tell the whole story about any given student. The numbers might, for example, point to a student who might be excelling in grades but needs help in other areas, and would then be ignored by the predictive system. As PSC Treasurer Sharon Persinger said, “As a numbers person, I think there’s more to students than numbers.” Persinger is an associate professor in the department of mathematics and computer science at Bronx Community College.

John Paul Narkunas, associate professor of English at John Jay College, asked a question posed by every faculty member and scholar interviewed for this article, “Who owns the [student] data?” Narkunas, author of Reified Life: Speculative Capital and the Ahuman Condition (Fordham University Press, 2018) wonders, “Is CUNY going to use the data sell it or even more insultingly, pay all this money to the company and let the company keep it?”

EAB, the company that will provide the analytics for CUNY, was acquired last year by private equity firm Vista Equity Partners. Private equity has been responsible for significant layoffs and union-busting in both the public and private sectors.

To Narkunas, whose book focuses on higher education and neoliberalism, the deal is yet another example of “financial capitalism trickling into our public institutions.” A contract like this puts significant tax dollars and enormous power in private hands, Narkunas says. “The contract is an opaque model for public accountability – private actors who don’t have to reveal anything.”

Indeed, Reuters reported in 2014 that major public pension funds had investments in Vista, the details of which were hidden by confidentiality agreements. According to the news agency, the agreements highlighted “how important aspects of the investment of public money in private equity are shrouded in secrecy.”

EAB said in a May 2018 blog post that predictive technologies are used not only by colleges for their enrolled students, but for prospective students – a “new market” that colleges can enter to seek potential enrollees. EAB wrote, “[M]any colleges are running basic analyses to identify pools of students who fit their desired profile, usually [focusing] on grade-point averages, proximity and the like. These analyses are typically based on historical enrollment data and basic student academic information. Though helpful, the view afforded by these analyses is still too limited to inform the decision to enter a new market, given the complexity, costs and trade-offs involved.”

EFFECTS OF AUSTERITY

CUNY’s communications office did not respond to Clarion’s request to interview a member of the administration about the EAB contract. However, a CUNY study on the use of technology for the years 2016 to 2020, “The Connected University CUNY Master Plan,” noted, “Through a cost-sharing agreement with CUNY’s system administration, CUNY’s 11 senior colleges are poised to join EAB’s (Education Advisory Board) Student Success Collaborative (SSC) in 2016 – a consortium of colleges that use EAB’s predictive model to improve retention and graduation rates.”

It continued, “There is no substitute for quality, in-person advising, but we live in an age when technology can reduce the effects of less than optimal numbers of counselors and advisors. As funding permits, the university will continue to hire well-trained professionals to provide the critical support that so many students need, but at the same time will monitor advances in technology that can assist a highly burdened advisement network in areas that can contribute to student success.”