|

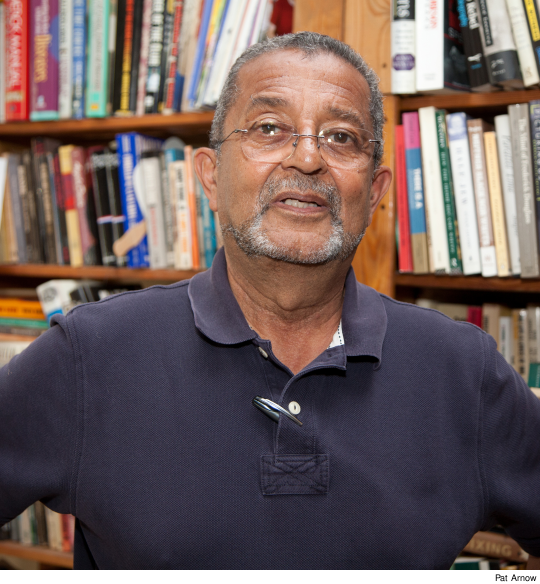

Larry Rushing, a professor of psychology at LaGuardia Community College, was attending a symposium in Cooperstown, New York, on May 31, 2012, in which he suddenly found himself disoriented and unable to remember his own thoughts. Later that night, he suffered chills and shivering for an hour while resting in his motel room. The following day he had no appetite. Two days later, he fainted while walking his dog.

“I didn’t know what was going on,” Rushing said of his unexpected malady. “But that’s when I knew this was something serious.”

HOSPITALIZED

Rushing, 74, landed in the hospital for four days where he received a pneumonia diagnosis and was successfully treated with antibiotics. Two weeks after leaving the hospital, the New York City Department of Health (DOH) contacted Rushing and told him that his mystery illness had in fact been Legionnaires’ disease, a severe form of pneumonia that can be lethal for people who are older or have compromised immune systems. About a month after he fell ill, the building where Rushing worked was identified as a possible source of his infection.

Legionnaires’ disease is contracted by breathing water mist containing legionella bacteria. These bacteria are not uncommon in the environment, and most exposure to the bacteria does not result in illness. A majority of cases of the disease originate from man-made water systems such as hot water tanks, large plumbing systems, cooling towers and evaporative condensers of large air-conditioning systems, where warm (77-108° F), stagnant water provides optimal conditions for the growth of the bacteria in high concentrations. Legionnaires’ disease, however, cannot be passed from one person to another.

The disease gained its name from a deadly outbreak that followed a 1976 American Legion convention in Philadelphia hosted in a hotel with a contaminated air conditioning system. Each year, 8,000 to 18,000 people are hospitalized annually in the US with the disease, though many infections each year remain undiagnosed and unreported. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration says that about 15% of cases are fatal.

SECOND CASE

DOH investigators determined that Rushing was the second LaGuardia employee in the campus’s C Building to have contracted Legionnaires’ disease in the past year and notified the college on June 26, 2012 of the possible contamination. Members of the college’s PSC chapter told Clarion that the administration took prompt action in response to the information from the DOH, but was slow in informing the union.

LaGuardia’s first move was to hire Olmstead Environmental Services to investigate. Olmstead took samples at the C Building on July 1, 2012. The results showed that domestic hot water collected from a fourth floor sink had “significant levels” of the legionella bacteria. The PSC has previously worked with the company’s owner, Edward Olmstead, and Jean Grassman, co-chair of the PSC’s Environmental Health & Safety Watchdogs, said she was pleased with the college’s decision to hire his company.

“They brought in someone that everyone agrees is a trustworthy consultant,” Grassman said “He’s very good at getting to the bottom line – what you need to do to change conditions.”

Olmstead’s report was completed July 22, 2012. The college immediately shut off the hot water systems in the C Building and subsequently “super-heated” the domestic hot water system serving the C Building to temperatures above 160 degrees Fahrenheit for more than four hours. Each hot water outlet was flushed with boiling water, an operation that had to be done when the building was closed.

Olmstead did a second round of testing of the hot water systems on August 2, 2012, this time in the B, E and M Buildings. Results showed elevated levels of legionella bacteria in the B and M Buildings that were anywhere from two to six times greater than what had been found in the C Building test samples. Though no contamination was found in the E building’s hot water system, the college had all three buildings decontaminated.

The college did not notify the union about the possible risk of legionella at LaGuardia until July 23, the day after Olmstead submitted his report, when Vice President of Administration Richard Elliott sent an e-mail to PSC Chapter Chair Lorraine Cohen describing the situation.

IN THE DARK

Danny Lynch, vice chair of LaGuardia’s PSC chapter, praised the administration for taking “reasonable” steps to address the crisis. Still, he added, “I don’t understand the rationale for not informing the union until a month after the report from DOH.” “There has to be a sense of transparency in the operations of the University, especially when it comes to health,” Lynch told Clarion. “We’re supposed to be partners in the workplace.”

|

Rushing said he was also disappointed that the college was not more forthcoming about the DOH report: “It would have been advisable to notify people that two individuals had contracted Legionnaires’ and that we’re testing for it on the campus,” he said. “Why not do it?”

“We couldn’t tell the college community that these two individuals had Legionnaires’ disease until it was confirmed that the disease had come from here,” said LaGuardia spokesperson Susan Lyddon. “As soon as it was appropriate, we notified the entire college community.”

Once apprised of the situation, the PSC chapter leadership stayed in close touch with Grassman and other members of the PSC Health & Safety Watchdogs. “The Health and Safety Watchdogs are a terrific resource,” commented Lynch. “They caught us up so we could ask detailed, specific questions about what occurred and what was to be done as far as the remedial treatment of the water supply.”

RECOMMENDATIONS

In addition to Olmstead’s recommendations for how to deal with the immediate crisis, his report also recommended:

• Repeating the super-heating process on a monthly basis;

• conducting periodic sampling of the system to verify that regrowth of the legionella bacteria is not occurring;

• and in the longer term, installing an ultraviolet disinfection and filtration system.

Lyddon told Clarion that the college now intends to super-heat the hot water systems in all four buildings twice a year and that it will test for Legionella in those same buildings on an annual basis. She also said that the college is currently trying to figure out the best place in the water lines to put the disinfection and filtration system recommended by Olmstead, though there is no timeline for completing the project.

Lynch said the union will be vigilant going forward: “We have to become our own watchdogs and make sure the University follows through on Mr. Olmstead’s recommendations.” Labor-management meetings, he said, can provide a venue for those discussions.

Grassman told Clarion that the outbreak at LaGuardia should serve as a wake-up call to the CUNY administration as the University has aging buildings on many campuses that could be susceptible to legionella outbreaks.

“They need to have a regular maintenance program for legionella, or this will happen again,” Grassman said.