|

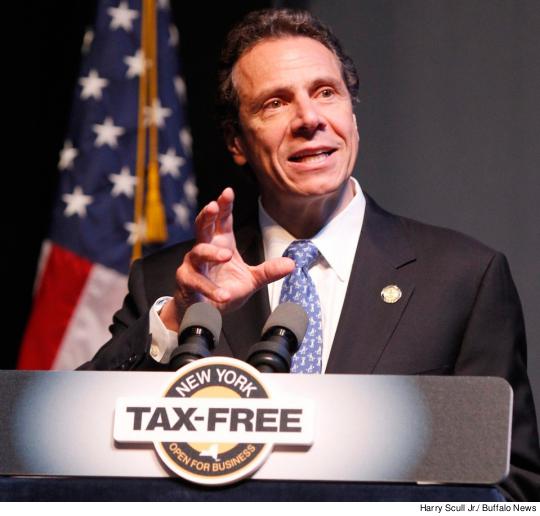

“Tax-Free New York” was the program’s original title when it was first proposed by Governor Andrew Cuomo a year ago. Soon rebranded as “START-UP NY,” its terms are extraordinarily generous. Using space at SUNY and CUNY college campuses, participating businesses would pay no state or local taxes at all for ten years – no payment of sales, business or property taxes. Their employees would pay no state or local income tax for five years, and for the next five years, individuals would pay no taxes on income of up to $200,000.

START-UP NY was approved by the Legislature last summer, and slick 30-second commercials promoting it were aired during the NFL playoffs. The TV ads showed hard-working people in high-tech jobs, from corporate offices to factory floors. But many economic development experts are skeptical about the program’s future results, and what it will mean for CUNY is only starting to be defined.

Marilyn Rubin, professor of public management at John Jay College, describes the tax breaks in START-UP NY as “sweeping” and “unusual.”

“I was very surprised when I saw ‘no taxes,’” said Rubin. “I haven’t seen anything quite as expansive anywhere, certainly not in such a wide geographic area.”

Unsupported by Research

Rubin is co-author of a report on business tax credits prepared for the New York State Tax Reform and Fairness Commission last November. There is “no conclusive evidence from research studies conducted since the mid-1950s to show that business tax incentives have an impact on net economic gains to the states,” the report concluded. “Nor is there conclusive evidence from the research that taxes, in general, have an impact on business location and expansion decisions…. Other costs of doing business generally take precedence over taxes in [these] decisions.”

“Any program that gives a 100% tax break is not a good idea,” says Josh Kellerman, a policy and research analyst with ALIGN (Alliance for a Greater New York). “It just seems overboard.” In business location decisions, factors like infrastructure quality or the education of the workforce are far more important than taxes, he told Clarion. “Those are funded through tax revenue,” he noted.

ALIGN is not against all tax credits, said Kellerman. “Strategically targeted, transparent subsidies” have a role to play, he said – but clear standards are key. [Last year ALIGN examined 15 New York incentive programs, and found that only three set any specific performance goals. “While ostensibly intended for job creation, the vast majority of programs do not require the creation of a single job,” it concluded.

START-UP NY rules do require new job creation and impose some penalties if job targets are not met. But the program’s outreach materials note that “there is no minimum requirement for the number of net new jobs that must be created.”

Leslie Whatley, a former Morgan Stanley executive whom Cuomo appointed to head START-UP NY in October, says the governor’s office hopes the program will create 10,000 new jobs per year, though she readily acknowledges that’s only an estimate. “We are taking land and space that is currently underutilized and trying to put business in it,” said Whatley. “So what we’re counting on is that we’re going to create an economic multiplier with excess capacity that’s in the system that creates a net positive.”

Joining campuses and startups together on business development and research can create “a very powerful economic engine,” Whatley says. “The fundamental of the knowledge economy is a partnership between business and academia.”

While the ads and press releases for START-UP NY emphasize high-tech employment, Whatley’s own past experience is not in the technology sector. “Ms. Whatley has had an accomplished career in real estate,” said the press release from the governor’s office announcing her appointment. “Most recently she served as Global Head of Corporate real estate at Morgan Stanley. Prior to that she was the Global Head of Corporate Real Estate at JPMorgan Chase.”

The governor’s office has estimated that the state will lose $323 million in tax revenue over the next three years thanks to companies that would have located in New York anyway, but which will now take advantage of the new tax-free zones; other experts say the amount of lost revenue may well be higher. Local governments will lose the associated property tax revenue that those businesses otherwise would have paid. The State will not reimburse them for this loss, which could affect some of the poorest school districts in the state.

“The governor’s START-UP NY program creates more loopholes at a time when the state can least afford it,” Andy Pallotta, executive vice president of NY State United Teachers, said last year. “It would greatly diminish much-needed revenues that could be going to schools, four-year campuses and community colleges. It is bad policy.”

Another criticism leveled at START-UP NY has been its potential to undercut existing employers in New York. It’s a legitimate concern, says Ron Deutsch of the progressive tax reform group New Yorkers for Fiscal Fairness: “You could have a local business that’s not expanding, but doing okay; then you have a competitor coming in from another state setting up a similar business. And not only do you now have to compete with someone who’s not paying any taxes, but you, as an existing business, are subsidizing them to pay no taxes.”

START-UP NY’s regulations say that businesses “that would compete with other businesses in the same community” cannot participate. However, nothing in the rules would keep a START-UP NY participant in Rochester from using its tax-free status to undercut an existing business in Syracuse, and the issue is hard to define with precision. More clear-cut are START-UP NY rules excluding businesses such as restaurants, medical practices or real estate brokers – types of businesses that, by their nature, must be locally based and cannot “run away.”

“We have many reasons to be skeptical, because past economic development programs have been spotty in terms of what they’ve delivered to the public,” comments Elizabeth Bird, a research analyst with Good Jobs New York. “Generally the research shows that it’s a much better investment to use government resources to strengthen infrastructure, educate the workforce and invest in quality services.”

Many economic development specialists say that there are strong arguments for colleges and universities to play host to “business incubators,” that can help locally based small businesses get off the ground. Young companies can tap faculty expertise, they say, while students get real-world experience and connections for future employment. “Campus incubators are growing,” The New York Times reported in 2012. “New data from the National Business Incubation Association show that about one-third of the 1,250 business incubators in the United States are at universities [in 2012], up from one-fifth in 2006.”

But when experts list the factors that make a business incubator succeed or fail, the key elements they cite are mentorship, access to capital and shared services. Tax incentives don’t tend to come up. A 2013 Forbes profile of “The 10 Hottest Startup Incubators” notes that they are “typically attached to universities,” but does not mention tax incentives once. A list of “best practices” from the National Business Incubator Association also says nothing about taxes.

“Business incubators are especially good for businesses that are just trying to get off the ground,” says ALIGN’s Kellerman. “Low-cost rent, shared space – these are great ideas.” By making it easier for a business to pay its initial start-up costs, he said, they allow the fledgling company to put more of its capital toward production. In contrast, with START-UP NY the companies operating on the largest scale – the ones with the largest profits, or that make the most purchases – will reap the biggest financial rewards from their tax-free status. Most of START-UP NY’s cost to the public may thus be spent helping companies that are already well-established.

On CUNY Campuses

START-UP NY actually stands for SUNY Tax-free Areas to Revitalize and Transform Upstate NY – and as the name suggests, it was designed primarily with SUNY in mind. But it also includes one CUNY school in each borough: Bronx Community College, City College, Medgar Evers College, York College and the College of Staten Island.

To participate in START-UP NY, each CUNY college must submit an overall plan for approval by the State. These campus plans must include: a description of the space or land “proposed for designation as a Tax-Free NY Area”; the type of businesses that could be included; how this plan serves the academic mission of the school; and the process that will be used to select businesses for participation. Companies that then apply must be approved by both the college and the State.

In January, Bronx Community College President Carole Berotte Joseph noted that BCC offers a degree program in biotechnology, “and yet we don’t have a lot of biotech companies in the Bronx. We have students who are going through this program who will need internships, who will need jobs, so it would be an excellent match.”

But while the SUNY schools that were the original target of START-UP NY often have open land or space, CUNY campuses are more often bursting at the seams. When Berotte Joseph made an announcement about START-UP NY at a College Senate meeting this semester, Sharon Persinger, BCC’s PSC chapter chair, says the lack of available space was raised as an issue. “We’re pretty much filled to capacity. We continue to use classrooms in basements without windows,” said Persinger. “I don’t know how a company that needs be here from 9 to 5 will fit in.”

No Funding

Joseph says her school has been “looking at spaces adjacent to the college”; the Medgar Evers College administration said earlier this year it hopes to rent the vacant Bedford Union Armory, slated for redevelopment, to provide startup space. While START-UP NY includes no funding for rented space, colleges could try to cover such costs by the rent they charge to participating businesses. This would make it more difficult, however, to offer the kind of low-cost rent that business incubators often provide.

START-UP NY rules state that “no academic programs, administrative programs, offices, housing facilities, dining facilities, athletic facilities, or any other facility, space or program that actively serves students, faculty or staff may be closed or relocated in order to create vacant land or space to be utilized for this program.”

City College is still considering what spaces on campus it might use for the program. PSC Chapter Chair Alan Feigenberg says the college administration is expected to have a proposed plan ready for review in May. The proposal will be presented to CCNY’s Faculty Senate, the campus PSC chapter, student government, community groups and local officials – all of whom will have a chance to review and comment before the proposal is forwarded goes to CUNY central administration.

The process hasn’t been as transparent at York College. Delegate Assembly Member Scott Sheidlower said York College President Marcia Keizs announced at a recent College Senate meeting that York’s application has been sent to Empire State Development, without any review from the college community. START-UP NY regulations require sharing the campus plan with a college’s faculty senate, union representatives and student government at least 30 days before it is submitted to the state.

“Telling us about it is not consulting us,” said Sheidlower, who raised this concern at a heated labor-management meeting in May. “Consulting is taking a program and asking for feedback, not notifying us.”

When asked by Clarion about the lack of notice, York officials said the plan had not been officially submitted, but only shared with the State to seek guidance. The same day that Clarion inquired, York’s administration shared its draft plan with the college’s Faculty Caucus for the first time. It did not share the plan with the union, as START-UP NY regulations equally require.

In an emailed statement, York’s administration said it is working with its partners on finalizing a proposal. “Once the York College final draft is ready,” the email stated, “we will submit it to our stakeholder groups for the requisite 30-day review.”

At the College of Staten Island, PSC Chapter Chair George Sanchez recommended that the college include a PSC representative on its START-UP NY advisory committee.

“START-UP NY is bad policy for New York State,” said PSC First Vice President Steve London. “Instead of handing so much revenue over to private interests and hoping for the best, it would make much more sense to invest those funds in the public services that can strengthen New York’s economy in lasting ways.”

At the campus level, London said, it’s essential that any plan, and any application by individual businesses, receive thorough, transparent discussion by the entire college community. “No enterprise that wants to offer real benefits to students, faculty and staff should fear such scrutiny,” London said.

______________________________

Some portions of this article previously published in Neil deMause’s article “Launch Sequence,” in the January 8 Village Voice.