This article is adapted from a November 7 presentation at “Somos El Futuro,” the annual New York Hispanic legislative conference.

______________________________________________

In this political moment – with economic crises, large budget deficits, political instability and calls for austerity measures – how can we shape policies to increase Hispanic access to college and success in completing a college degree?

One thing is clear: austerity policies are moving us in the wrong direction. Instead, we need public investment that will allow CUNY and SUNY to be “engines of equality.”

Social policies must respond to the stark reality of extreme income inequality in the US and in New York State, and the disparate impact of the Great Recession on communities of color and working-class New Yorkers as a whole.

New York State and City have experienced a decades-long trend toward greater income inequality. Not only are the rich getting richer, but the poor – especially during the Great Recession – are getting poorer faster. While Wall Street firms saw their profits skyrocket in 2009 to over $60 billion, the child poverty rate in Mott Haven and Hunts Point in the Bronx was 56%. New York City’s overall poverty rate was 22%, while NYC’s Hispanic poverty rate was nearly 29%.

EXTREME INEQUALITY

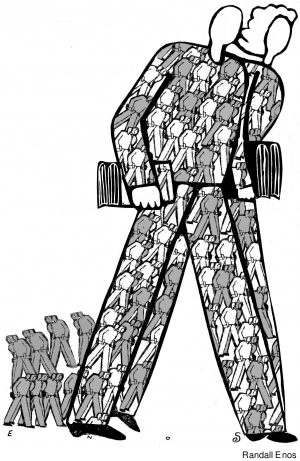

In a December 2010 study, the Fiscal Policy Institute (FPI) found that in 2009 New York State had the greatest degree of inequality among the 50 states and New York City had the greatest degree of inequality among the 25 largest US cities. Nationwide, in 2007 the share of total income in the US that went to the highest-earning 1% hit a historic high of 23.5% – last reached in 1928. But 2007 data for New York shows that here, the problem was even worse: in New York State, the richest 1% of households received 35% of total income, while in NYC, the top 1% got an incredible 44% of all earnings in the city.

Adopting policies to reverse these trends is the chief challenge we face in this political moment. The extreme income inequality of our society leads to broken lives, wasted resources, and social and political instability.  Government can be an instrument promoting greater equality or it can become an instrument to intensify inequality.

Government can be an instrument promoting greater equality or it can become an instrument to intensify inequality.

Economic challenges don’t have to lead to greater inequality. In the Great Depression, for example, New Deal policies favored greater equality, and this helped put our economy on a firm foundation.

HISPANIC ACCESS

Austerity budgets at this time move us in exactly the wrong direction. To provide greater access and assure greater success in college for the Hispanic population, public investment is required. The case is even clearer when we consider the large demographic wave of Hispanic students making their way through the K-12 school system or already in college.

- Hispanic students now comprise 28% of all CUNY undergraduate degree enrollments; 24% at the senior colleges and 36% at the community colleges.

- Hispanic students comprise 44% of all CUNY freshmen – a huge increase over the last five years.

A failure to help New York’s growing population of Hispanic students succeed in college would mean a huge cultural and economic loss for all of New York State. Conversely, investing in the education of our growing Hispanic population can be an important part of the solution to our current economic problems.

Unfortunately, New York has pursued a long-term policy of disinvestment in public higher education. In real dollars, State funding per full-time-equivalent (FTE) student has fallen for both SUNY and CUNY since 1990. Governor Spitzer’s Commission on Higher Education and the FPI have amply documented this long-term disinvestment and its destructive consequences.

New York is also one of the worst states when it comes to making an “effort” to publicly fund higher education. In 2008 and 2009 (even with stimulus money counted in) there were only 10 states that gave higher education less support than New York, per $1,000 of personal income. In other words, New York has devoted a smaller share of its wealth to higher education than 39 other states.

This long-term disinvestment particularly hurts those Hispanic and other students at CUNY:

- who are low-income – 38% of all CUNY undergraduates and 45% of all community college students come from households earning less than $20,000 per year.

- who are graduates of NYC public high schools (69%) and need remediation (50% of NYC HS graduates who entered CUNY in 2009).

- who are the first generation in their family to attend college – 43%.

- who speak a native language other than English – 45%.

- who have substantial family or work responsibilities.

Hispanic students, in particular, are likely to meet additional hurdles while attending CUNY. They are more likely to enter CUNY at the community college level where there are fewer full-time faculty for each student. (The full-time faculty to student ratio is 1:47.) They are also more likely to need developmental courses, including instruction in English as a Second Language, to make up for deficits in their high school preparation before beginning credit-bearing college courses.

MEETING THE CHALLENGE

Given these obstacles, it is not surprising that Hispanic students take longer than white students to graduate with either an associate or baccalaureate degree. After six years, the graduation rate of all CUNY community college students with an associate’s degree is 24.3%. But white students do better. After six years, 32.2% of white students earn an AA degree, compared to only 22.9% for Hispanic students. This racial inequity diminishes over a longer period, but even at eight years, the graduation rate of Hispanic students is only 30%. (The situation facing African American students is similar.)

So, what must be done to improve opportunities for Hispanic students and others?

First and foremost, more resources are desperately needed to give Hispanic students the support they deserve. Amid record-high admissions to CUNY, unfortunately, we have experienced cuts to the senior and community college budgets, followed by additional midyear cuts, with results that are seen in the poor physical plant, higher class size and weakened student support.

TAPPED OUT

These additional resources need to come from greater investment of public funds. The gap between current funding levels and what CUNY and SUNY need to create the conditions for Hispanic access and success is so large that relying on tuition increases for additional resources is simply unrealistic; our students are too poor to provide the system with that much money.

New York’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) and Federal PELL Grants assist many students, but they do not adequately cover all, especially those enrolled part-time or who are financially independent without dependents. Thus, TAP does not protect many of our students from the impact of higher tuition. In addition, much financial aid involves the student assuming debt, and research has shown that many poorer students are reluctant to take out educational loans.

The PSC commends the legislative leadership for rejecting the Public Higher Education Empowerment and Initiative Act (PHEEIA), because such privatization proposals move us in the wrong direction. As a proposal, PHEEIA was accompanied by cuts in public funding. At its core, PHEEIA would force public higher education funding to rely more and more on tuition increases and unaccountable public authority-like frameworks. (See Clarion, Sept. 2010.) To provide accessible, quality public higher education, there is no substitute for public investment.

New York can raise additional public funds by adopting progressive revenue measures and closing corporate tax loopholes. (See page 11.) Two decades of tax cuts favoring the wealthy are an important part of the story of increasing income inequality in New York State. If we truly believe that all students deserve equal access to a quality public college education, we need to reverse these tax policies that favor the well-to-do.

WHAT WE NEED

What must CUNY and SUNY do with greater resources?

- Most immediately, we need to hire more full-time faculty so they will have the time to meet with and mentor students – and we need more full-time faculty who are themselves Hispanic. In 1975, CUNY had 11,500 full-time faculty and 250,000 students. Now, with more students who need more educational and support services, we have only 7,000 full-time faculty. The deficit is made up of thousands of adjunct faculty who are very dedicated and excellent teachers, but are underpaid, treated as contingent labor, and not hired to perform many of the duties and student support activities of full-time faculty. For all these reasons, current research demonstrates greater student success when taught by full-time faculty.

- TAP must be reformed to make it more equitable. New York needs TAP support for part-time students, and increased support for financially independent students without dependents. If tuition continues to rise, the cap on TAP grants also needs to increase.

- Additional financial aid counselors are needed to support students applying for financial aid – including simply filling out federal FAFSA forms. Too many immigrant and Hispanic students don’t receive Pell and TAP grants even though they are eligible. More academic counselors and better coordination with high school advising are also needed.

- Expansion of “College Now” and similar programs can play an important role. Many studies on Hispanic college success have underscored the importance of making sure students have rigorous college-track courses in high school so that they gain the skills they need and know what to expect when they enter college. This can be true for all students, but is especially true for Hispanic students who are the first generation of their family to go to college.

- Resource-rich academic, career and mental health counseling services are needed – especially for incoming freshmen. For example, the new ASAP program has succeeded in raising retention and graduation rates among a representative sample of community college students. But each program has two to four college advisors carrying an average caseload of 60 students, a career and employment specialist to help students find paid internships while going to school, and three clerical staff. Outside ASAP, the ratio of mental health counselors to CUNY students alone is less than one to 2,000.

Continued cutbacks for CUNY and SUNY would mean a future of increasing inequality for New York State, with growing exclusion from the chance to earn a college education. If we believe in inclusion, if we believe that Hispanic community leaders are right to say, “Somos el futuro!” then more public investment in higher education is a necessity.

Supporting CUNY as an engine of equality will benefit the Hispanic community – and everyone in New York.