Over the last decade and more, many artists have been concerned about a broad array of social issues. Commitment to social commentary and criticism through artworks is viewed as a move beyond the art-for-art’s-sake limitations of liberal modernism: the artist as social isolate. But is this move toward the social really all that substantial? I think it depends upon how we come to view the role of the artist. My commitment has long been that the concerns and exhibition of social art be connected in some way to organized efforts towards the same ends; art that intends to challenge the social world has its best chance in tandem with social/political organizations and their allies.

– Fred Lonidier

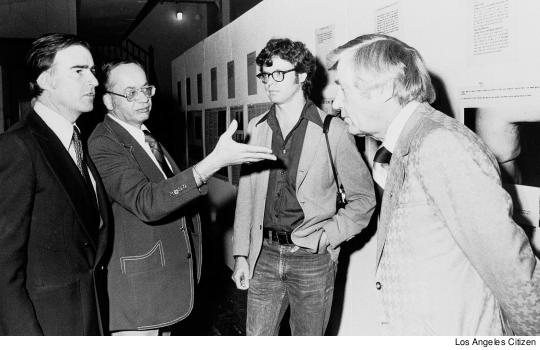

Fred Lonidier is a San Diego-based artist whose work is among those featured in this year’s Whitney Biennial. He’s likely the only participant who’s also a union activist. A founding member and past president of American Federation of Teachers Local 2034 at the University of California-San Diego, Lonidier has put labor struggles at the center of his art for nearly four decades.

Lonidier’s unionist pedigree, questioning of art world practices, and history of showing work in union halls and labor-friendly spaces all inform the quality of his work, which engages with class, not only in its themes, but in how, where and to who it is presented. These characteristics make Fred Lonidier a possibility model for politically minded artists in the age of Occupy.

“It wasn’t just the politically provocative photographs that got Fred Lonidier’s exhibit at Tijuana’s public university taken down,” reported CorpWatch in 1999. “It was the fact that he had the audacity to leaflet maquiladora workers outside the factory gates and invite them to the gallery that got his show yanked.”

Like much of Lonidier’s recent work, the Tijuana exhibit focused on worker exploitation and resistance in Mexico in the NAFTA era. Administrators at the Autonomous University of Baja California ordered the show to close, explaining in an email that there had been complaints from “some members of the industrial community” about the factory flyer distribution. “The leaflet brought the show down,” Lonidier commented later. “If I hadn’t leafleted, they would have kept it up.”

Not Easily Deterred

But Lonidier is not easily deterred. He was back in 2003 with an exhibit titled “‘NAFTA…’ Returns to Tijuana/‘TLC…’ Regresa a Tijuana,” a “traveling exhibition” in the most literal sense: the work was mounted inside a semi-trailer truck similar to those that carry maquiladora products over the border every day. It was a venue that, while expensive, made censorship more difficult. In addition to touring maquiladora zones near Tijuana, the truck made stops north of the border at University of California, San Diego (UCSD), where Lonidier worked, and at San Diego City College, where Enrique Davalos, who helped organize the rolling show, is a professor of Chicano studies.

At times like these, Lonidier’s documentary photo/text/video installations can bridge the divide between the art world and union struggles. Or start to: it is not always an easy bridge to cross. “Union members and workers generally are going to engage with my [artworks] in relation to the familiar work and struggle worlds they know, but I have received back a general recognition that my installations are sort of like and not like anything else with which they are familiar,” Lonidier told Clarion.

“They know that modern art often takes unusual forms,” Lonidier wrote in a 1992 essay, “Working With Unions II.” While this in itself “is not a satisfactory understanding of what I do,” he said, it can be a starting point for a dialogue, an exchange from which both parties can learn.

|

“I always look for the submerged, missed, or forgotten labor issue – or for an issue that is about to emerge,” Lonidier explains in his 1992 essay. “I look to the absences, inadequacies or invisibilities of the available discourse. In fact, much of what I have to say is already known and discussed or suspected by workers themselves. It may only be a question of legitimizing or distilling and organizing certain ideas rather than teaching in the one-way sense.”

Lonidier’s work and his path in the art world go back to his hiring by UCSD, his alma mater, where he earned his MFA in photography and is now professor emeritus. An early center for conceptual art, Lonidier’s department was the kind of place that could welcome an artist with a bachelor’s degree in sociology.

The 2014 Whitney Biennial (March 7-May 25) will feature “‘NAFTA.…’ Returns to Tijuana/‘TLC…’ Regresa a Tijuana” and “GAF Snapshirts,” a 1976 installation of 32 custom photo T-shirts. Lonidier describes the latter as a “sort of political pop art” that preceded his turn toward “artworks by, for and about class struggle.”

The first of these more labor-centered works, “The Health & Safety Game” (1977), is being exhibited from February 27 through March 30 at Essex Street, a gallery on NYC’s Lower East Side, in conjunction with the biennial. Originally shown at the Whitney and at AFSCME District Council 37 in 1977, in what was billed as a joint show, it is an installation of a large number of photo/text panels and a 20-minute black and white video. It includes close-up, documentary photographs of anonymous workers’ injuries (titled “Steel Worker’s Lungs”, “Dental Technician’s Back” and so on), panels arranged in the case-study style of corporate reports offer brief descriptions of workers’ conditions, treatments and how they are fighting back, as well as displays of “management strategies” used to avoid paying for workers’ care and compensation.

“It is a representation of the political economy of occupational health that is unfortunately as current today as when it was created,” says Lonidier. Essex Street will follow up in June with a show of Lonidier’s more recent works, including his maquiladora-focused art.

The Art World and the Union Hall

While taking class conflict as his subject matter, Lonidier also challenges art-world rules: How should documentary photographs be presented, what place does a photo-journalistic aesthetic have in high art, how can common symbols and pieces of working-class life be utilized within art – while giving viewers a lot to chew on?

“He [can] present workers’ injuries as a zero-sum game or other rational calculus for employers while simultaneously tweaking the sensibilities of lovers of cutting-edge art,” said artist Martha Rosler, who studied and worked with Lonidier in the 1970s at UCSD. “In addition, he chose to present textual material in three formats – short and simple, slightly longer, and more detailed – thus allowing audiences to take in as much of the text as they desired.”

Artist and critic Allan Sekula wrote that Lonidier’s “The Health and Safety Game” lays bare the “systemic character of everyday violence in the workplace.” One could imagine a panel called “Fulfillment Center Worker’s Legs” in this era of online shopping mega-warehouses.

“Including Fred’s work in the Whitney Biennial represents an embrace of an artistic and political practice that stems from documentary, but works with a different sort of activist approach,” said Rosler. “It recognizes the place of Lonidier’s work in the long tradition of documentation of working-class jobs, often those held by men in industrial settings – but not only.” Lonidier’s artwork does not portray workers as “other,” which, according to Rosler, is part of why it hasn’t been as widely acknowledged by the mainstream art world. But that may be starting to change.

“At its best, his work is free of the self-righteousness so often attached to social responsibility and gives voice to people who need it, often in contexts that rarely permit it,” wrote Natalie Haddad in a 2011 review in Frieze.

The biennial’s high profile in the art world certainly gives Lonidier a boost in those circles. Lonidier is optimistic that it can also be used as a way to connect with at least some union members. “New York is a more art-conscious town than almost any other in the US,” he told Clarion. “Certainly a lot more union members will know about the show than would be the case for anything similar in San Diego.” To build on those chance connections, Lonidier is working on outreach to union audiences for public discussions he is planning in New York.

At the Whitney

The evening of Friday, March 7, which is a pay-what-you-wish night at the Whitney, Lonidier will join the crowd at the biennial, near his work, to talk with interested visitors between 6:00 and 9:00 pm.

On Sunday, March 9, at 2:00 there will be an in-depth discussion with the artist at Essex Street on the Lower East Side, where Lonidier will show more of his labor artwork in June.

“What I hope to achieve is what I have long done: bridge my work within the field to the labor movement,” Lonidier says.