A reporter digs into the divide

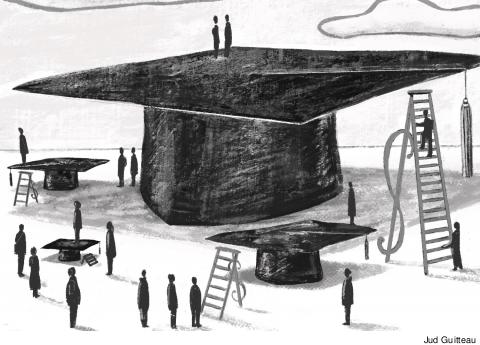

At the end of 2019, Chronicle of Higher Education senior reporter Karin Fischer wrote a lengthy report about how higher education in the United States maintains social stratification and remains largely unaffordable for large segments of the population. She asserts that American higher education is at a do-or-die moment: either we fix this problem now, or higher education “could be completely broken.”

It is a complex historical tale Fischer weaves, and she sees some signs of hope, including CUNY’s ASAP initiative, which despite being a popular and beneficial program, is sorely underfunded.

Fischer’s piece, “The Barriers to Mobility: Why Higher Ed’s Promise Remains Unfulfilled,” appeared on December 31. She recently spoke to Clarion editor Ari Paul.

The main takeaway of your piece is that “Instead of acting as a leveler, higher education magnifies economic differences and reinforces them.” Who’s to blame for this? Colleges, government?

The answer is everyone. The federal government’s spending on student aid programs hasn’t kept pace with mounting costs. State and local governments have failed to invest in public colleges, leading to rising tuition. Universities can make curricular choices, like remedial education, that frequently disadvantage lower-income students. The K-12 system often doesn’t adequately prepare students to succeed in college. You can even go back to community investments in infant and maternal health and early childhood education and see the long-term consequences for poor Americans. Because there are so many culprits, it’s hard to see a single fix, be it governmental policy on an institutional shift, that is a game-changer.

What made you interested in this story and how did you start doing the research?

The genesis of this particular article – which is the first in a longer series – was a collaboration between the Chronicle of Higher Education and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, but I’ve been writing about the socioeconomic divide in higher education and its consequences for more than a decade.

Over the years, I’ve written about everything from how geography can be destiny in educational attainment to community-wide efforts to attack educational inequities to the connection between education and poor health and early death. In terms of what drew me to the topic, I grew up in Newfoundland, Canada and Northern Maine – two poor regions where college-going is low – so I saw the difference education makes firsthand.

As far as research goes, it was a little like drinking from a firehose – there is a growing amount of data that illuminates education inequities, their causes and their consequences. The goal of this piece, as the first in a series, was to look at the post-World War II promise of college as a ladder to the middle class and where that promise broke down. It’s a lot to synthesize, and one of the biggest problems my editor and I faced was just how much research was out there.

You mention CUNY ASAP as offering “some lessons on what colleges can do to help low-income students succeed.” Do you think it could be a model around the country?

The CUNY ASAP model has already been adopted in other college systems and states, so we know it can be done. But that’s not to say it’s easy. It’s an approach that demands a lot of investment in time and money. Colleges have to offer dedicated advising, wraparound financial aid and be highly attuned to all the nonacademic hurdles that so often trip up students. I know CUNY spent about $16,000 more on each ASAP student than for his or her classmates. CUNY leaders, of course, argue that ASAP’s strong outcomes justify the spending. Still, will colleges – and the people who fund them – be willing to invest in such intensive interventions? Given that falling taxpayer support for higher education is one of the factors in the growing educational divide, I’m not sure how optimistic to be about ASAP catching on widely.

Having reported this story, what policy fixes – either at the state or federal level – do you think are necessary to make higher education a “leveler”?

There’s a need for multiple fixes. Take the national level: families, particularly those that are first generation, routinely get tripped up by the complexity of federal financial-aid forms. The value of the Pell Grant hasn’t kept up with inflation or rising tuition, so it now barely covers a third of the costs of college. Congress increased funding, but not nearly enough. Many of the experts I spoke with said the federal government has to do more to ensure that colleges serve low-income students, such as conditioning participation in the financial-aid system on enrolling a minimum percentage of Pell Grant recipients. On the state level, we know that during the recession, increasing tuition priced too many low-income students out of college, and legislatures hold public college purse strings. Over the past couple of decades, a number of states have moved toward grant programs based on merit, not need – or the programs have been more focused on middle-income students than tailored to aid the neediest. States can incentivize colleges to enact curricular reforms that could help low-income, first-gen and minority students access college and earn a degree. And these are just some of the policy levers.

You cover higher education internationally. Can the United States learn lessons from overseas about how to make college more accessible?

Unfortunately, ensuring educational equity is a problem overseas, too. When you look at countries that have enacted some variation of free college – that buzzword of the presidential primaries! – the way they’ve typically been able to do it is by limiting the number of spaces at public universities. And that ends up creating some weird dynamics. In Brazil, for example, almost everyone who benefits from free college at top-ranked public universities got there because they went to private high schools and could afford the kind of preparation that helps them gain admission. Germany, too, has free college, but it’s a very stratified system, where certain students get tracked into higher education and others don’t. One of the particular challenges of the American higher-ed system is that we really elevate the idea of equity of opportunity, and that makes other countries’ solutions hard to adapt.