When the PSC bargaining team met with CUNY negotiators in May, the spotlight was on the demand for 5 percent annual salary increases in each year of the contract for all titles. Current contracts for public-sector workers in New York State have uniformly been settled with raises of 2 percent per year. While achieving higher raises and exceeding the “pattern” set by other contracts is rarely accomplished, PSC negotiators made a compelling case.

It is important to understand the history of how CUNY salaries became substantially lower than those at comparable institutions in and around New York City and other prestigious universities around the country.

FISCAL CRISIS

Flash back to 1971 (the year of the first PSC contract negotiations, ratified in 1973): CUNY full-time faculty salaries were the envy of those at peer institutions – CUNY pay was substantially higher than salaries even at Columbia University, New York City’s lone Ivy League institution. CUNY was made to be an inclusive institution, and having the opportunity to teach at such a place and to live with a decent salary in New York City was considered a coveted job in the academic job market.

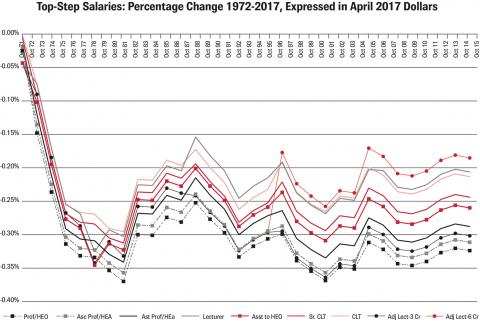

PSC research shows that, starting in 1971, salaries at CUNY began a precipitous drop in value, first because inflation was increasing faster than salary rates, and second, because of the New York City financial crisis of 1975. The chart above shows that inflation-adjusted top-step salaries for full- and part-time titles lost 25 percent to more than 30 percent of their value during the first half of the 1970s and then dropped even further during the second half of the decade.

CUNY suffered even more significantly from changes as a result of the 1975 financial crisis, when the city was at the brink of insolvency. Many remember the tension of the era – such as the Daily News headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead” – but sometimes forgotten is what happened to the city’s social democratic institutions, including CUNY. As a result, most notably, the state served disproportionate budget cuts to CUNY. Very few full-time faculty were hired – an entire generation of faculty was lost. A period of disinvestment in CUNY, which has persisted for decades, commenced.

The PSC has, indeed, won increases over the years, but those increases have been offset by the general decline in wages, in part thanks to inflation. The ongoing “salary erosion,” as Brooklyn College political scientist and PSC bargaining team member Steve London calls it, has occurred while CUNY wages are “trying to walk up a down escalator.”

FALLING BEHIND

The result today for CUNY is staggering. Look at the lists below – a Columbia University professor, on average, earns twice what a CUNY senior college professor earns, and often has subsidized Manhattan housing as part of the compensation package. Other public university systems in the region – Rutgers-Newark, University of Connecticut, SUNY-Stony Brook – offer more in salary on average than the CUNY senior colleges.

But that’s not even the whole story: public universities located in places where the cost of living is significantly lower than in New York still offer higher salaries. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill might pay “only” $33,000 more, on average, than the $126,500 offered at CUNY senior colleges, but factor in that it can be much easier, and cheaper, to move into a spacious house in the Triangle region than it is to find a one-bedroom in a walk-up within easy commuting distance of a CUNY campus.

ATTRACTING TALENT

The effect on CUNY – as the union has told the CUNY Board of Trustees, the City Council, the State Legislature and the press – has been that talented academics, despite being drawn to CUNY’s mission and its location in New York City, are often reluctant to accept full-time faculty jobs at CUNY. Why should one struggle paycheck to paycheck in New York City when one can live more comfortably and have a lower teaching load at, for instance, Penn State?

“This precipitous decline was due to the double impact of inflation and the New York City fiscal crisis,” London said. “The salary-steps’ real value decline hit bottom in 1982, and rebounded somewhat during the mid to late 1980s. But, the city and state austerity policies of the 1990s – along with tax cuts for the wealthy, under the first Governor Cuomo, Governor Pataki and Mayor Giuliani – led to five years of 0-percent increases over two contracts.”

As contract talks continue over the summer, the union’s bargaining team will continue to highlight this trend and press the need of correcting historic salary erosion.