|

Open Admissions at CUNY was born in the cauldron of grassroots protest. It came on the heels of a movement by blacks and Puerto Ricans for community control of local schools. In 1964 the police shooting of a black youth galvanized a march by 8,000 people, largely African Americans, in Harlem. In 1968, the nation was reeling from violent uprisings following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and it was also the year that a clash between teachers and the community school board in Ocean Hill-Brownsville led to a two-month teachers strike.

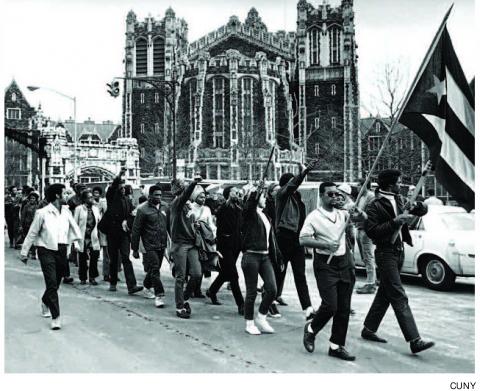

The specter of “cities burning” and the deepening split between the white establishment and aggrieved minorities stoked fears that New York City would suffer a similar fate. Then, in April 1969, over 200 black and Puerto Rican students padlocked the gates of City College of New York (CCNY) and renamed it the “University of Harlem.” Their major grievance was that African Americans and Puerto Ricans comprised 40 percent of high school students and 98 percent of Harlem residents, yet 91 percent of CCNY’s day students were white. In CUNY as a whole, whites comprised 87 percent of students in senior colleges and 68 percent in community colleges.

PROACTIVE CHANGE

As early as 1964, the Board of Higher Education (precursor to the Board of Trustees) expressed a commitment to “expand opportunities for poorer minority students” and established the CD College Discovery Program in community colleges and the SEEK Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge Program in senior colleges. In 1968 the board approved plans for the construction of York College, Medgar Evers College and Hostos Community College. It also conceived of an open admissions program that would guarantee every high school graduate a seat in a community college, to be phased in from 1971 to 1975.

However, the sheer force of the 1969 CCNY student strike led the Board to launch open admissions precipitously in the fall of 1970. Enrollment for first-time students leapfrogged from 19,959 in 1969 to 38,256 in 1972. Black students increased from 16,529 to 44,031; Puerto Ricans from 4,723 to 13,563. Notably, white students also increased from 106,523 in 1968 to 125,804 in 1972.

Unfortunately, open admissions was destined for a short life. The 1975 fiscal crisis pushed New York City to the verge of bankruptcy. Consistent with Naomi Klein’s concept of “disaster capitalism,” power brokers seized the opportunity to cut back open admissions and the SEEK Program. They also instituted tuition for the first time in 129 years.

MINORITY DECLINE

As PSC First Vice President Michael Fabricant and Professor Stephen Brier write in Austerity Blues: “While open admissions at CUNY remained in place, at least officially, the decision to charge tuition and tighten admissions standards, especially at the senior colleges, dramatically eroded the underpinnings of a truly open admissions policy… . CUNY suffered a decline of 62,000 students in its total enrollment by the end of the 1970s, with 50 percent fewer black and Latino freshmen among CUNY’s entering class than in 1980.”

The other shoe fell with the 1993 election of Rudolph Giuliani as mayor of New York City. In 1998, Herman Badillo, chair of the Board of Trustees, sponsored a resolution to phase out remedial courses at CUNY’s senior colleges. A few months later Giuliani impaneled a task force, led by Benno Schmidt, to undertake a sweeping review of CUNY. Within a year it issued “An Institution Adrift,” which described CUNY as “moribund” and in “a spiral of decline,” and it urged CUNY to “reinvent” open admissions with “…the placement of the remediation function in the community colleges.” Four years later, Schmidt declared that CUNY had made “stunning” progress and was now “the pride of the city.”

BAD RESULTS

The deleterious consequences of dismantling open admissions were brought to light in The Atlantic: “Since it went through an aggressive, system-wide overhaul that began in 2000, the City University of New York’s top five colleges – Baruch, Hunter, Brooklyn, Queens and City – have been raising admission standards and enrolling fewer freshmen from New York City high schools. Among the results has been the emergence of a progressively starker two-tier system: CUNY’s most prestigious colleges now increasingly favor Asian and white freshmen, while the system’s black and Latino students end up more and more in its overcrowded two-year community colleges.”

The Atlantic wrote: “This race disparity within the CUNY system widened most noticeably after the 2008 recession, when CUNY’s bargain tuition rates began drawing more middle-class families. Applications surged. That same year, CUNY increased its math SAT admission requirement 20 to 30 points for the five highly selective colleges. Department of Education records show that by 2012, the number of black public high school students enrolled as freshmen into the system’s top five colleges had decreased by 42 percent. Latinos dropped by 26 percent.”

WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

Not only have recurrent increases in tuition and SAT scores cut into minority enrollment in the top five senior colleges, but also since 1992, the SEEK Program has been cut in half. For decades SEEK offered racial minorities a doorway to senior colleges, but that door, too, has been steadily closed.

African Americans and Latinos now make up 72 percent of public school students. Their gross under-representation in CUNY’s senior colleges is a patent case of institutionalized racism and cries for redress.

What can PSC do to address the inequities that are baked into the system and result in a two-tier system, whereby the top five senior colleges are populated primarily by white and Asian students and the community colleges by black, Latino and other minority students? We have a responsibility and the power within our own domain to influence policy and enact change.

Stephen Steinberg is a distinguished professor of urban studies at Queens College and the Graduate Center. He thanks Dean Savage, a professor of sociology at Queens College, for his insights for this article.