|

Join the Demonstration!

Sunday, May 1, 2011 at 1:00 PM

Foley Square (Between Centre and Lafayette Streets), NYC

PSC will meet on SE corner of Foley Square at 12:45 pm

|

May Day is a celebration of international solidarity with roots in the United States. The international workers’ holiday commemorates the day in 1886, when laborers, immigrants, artisans and merchants in Chicago waged a general strike to win the eight-hour work day. It’s a day that recalls both our own immigrant histories and the ongoing struggle for the rights of working people everywhere.

Last year, for the first time in a generation, the New York City labor movement united with immigrants’ rights organizations to organize a demonstration on May Day. This year, a broad coalition of groups is continuing the fight.

Our demand today—for the rights of workers in the face of a rising tide of austerity and anti-immigrant rhetoric—is as urgent and transformative as our predecessors’ demand for the eight-hour day.

The general anti-austerity theme of May Day complements the more specific call of the PSC contract/budget rally on Thursday, May 5th for an end to economic austerity for CUNY, and a restoration of CUNY’s public funding. Join us for both rallies.

Contact Jim Perlstein, chair of PSC’s Solidarity Committee, to let us know you’re coming.

The History of May Day

May Day, the international workers’ holiday, began in the U.S.A. Its roots go back to Chicago, in 1886.

|

After the Civil War, the nation’s factories and mines were growing fast. They employed hundreds of thousands of new immigrants – German, Irish, Mexican, Chinese, and eastern Europeans – and tens of thousands of African Americans who had just won their freedom. Workers toiled 12, 14, and even 16 hours a day, for miserable wages and in dangerous conditions. During frighteningly long depressions, thousands of working-class families couldn’t find work and often starved.

But business owners and the mainstream press blamed this widespread poverty on individual failure – and on the growing number of immigrant and black workers, who they claimed didn’t share traditional “American values.” Unions had to fight this tide of prejudice, racism and mindless worship of “free markets” as they organized workers.

The emerging labor movement united around a demand to shorten the working day to eight hours. One national labor organization called for a nationwide general strike on May 1st, 1886, if Congress did not act to establish an eight-hour day.

1886 was a year of strikes and militant labor action across the country. People called it “the Great Upheaval” – and Chicago was a center of protest. The city was home to a powerful anarchist movement that included Texas-born Albert Parsons, Lucy Parsons (who historians think had both African American and Mexican ancestors) and August Spies (a German immigrant). With thousands of other workers, they prepared to strike for the eight-hour day.

When May 1st dawned, 60,000 Chicago workers went out on strike. Two days later, with the strike gaining momentum, the Chicago police shot two strikers and wounded dozens more at the giant McCormick Reaper Works.

The anarchists organized a demonstration to protest the shootings, on May 4th in Chicago’s Haymarket Square. As that rally neared its end, 200 police entered the square and demanded that the remaining protesters disperse. From the darkness someone (whose identity has never been determined) threw a dynamite bomb, killing one policeman and wounding 70 others.

In the chaos and hysteria that followed, the authorities smashed Chicago’s labor movement. The Chicago police arrested anarchist leaders Albert Parsons and August Spies and six others and charged them with murder – even though there was no real evidence against them. They were convicted anyway, and four of them, including Parsons, were hanged in Nov. 1887.

After 1886, workers and labor radicals around the world began celebrating May 1stas a day of international working-class solidarity to demand the eight-hour day. In 1890, huge May Day demonstrations in the U.S., across Europe, and even in Australia and Cuba demanded eight hours. The international labor movement denounced the frame-up of “the Haymarket martyrs” and demanded that those still in prison be freed. (They were pardoned by a pro-labor governor in 1893.)

American business leaders and the mainstream press wanted to distance the U.S. from May Day, because of its radical roots. With business support, in 1894 President Cleveland officially declared the first Monday in September as Labor Day.

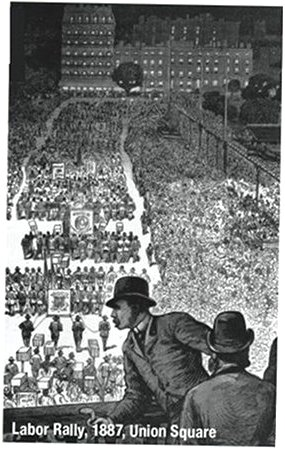

Around the world, workers continued to celebrate May Day as International Workers Day. In the United States, especially after the Russian Revolution, this made-in-U.S.A. holiday was denounced as “un-American.” Regular celebrations of May Day continued anyway, notably in New York’s Union Square. But after the 1930s, the left in the labor movement came under sharper attack, and U.S. May Day celebrations grew smaller and smaller.

Today May Day is coming back to the country where it began. Millions of immigrant workers from Latin America, Asia and Africa have come to the United States, bringing their own experience in union struggles. They have always known that May Day is the workers’ day.

As more immigrants join the U.S. working class and organize for their rights, immigration laws have increasingly been used to fire union members and break up union drives . In response, the labor movement started speaking out in support of immigrants’ rights. In 1999 the AFL-CIO called for repealing the anti-immigrant law that makes work a crime. Instead, it called for legal status for the undocumented, reuniting immigrant families, and protecting organizing rights for everyone.

On May 1st, 2006, millions of immigrant workers poured into the streets in the Great American Boycott, walking off the job and marching against anti-immigrant legislation then being considered by Congress. Many unions supported this May Day protest, and others in the years that followed.

Today May Day belongs to us all. We march to demand equal labor rights and jobs for all. We march to carry forward the May Day tradition that began in 1886, and renew it for our new century.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 153.42 KB |