The word comics brings up all kinds of associations. You might imagine a neighborhood comics store; walls lined to the ceiling with printed material depicting muscled women and men wearing outlandish costumes. You may think of the recent spate of blockbuster movies, featuring modern demigods like Captain America or the Incredible Hulk. Or maybe you’d think of independent comics artists such as Art Spiegelman or Adrian Tomine whose work is found on the cover of The New Yorker.

As comics art and graphic novels have become a stronger force in US culture in recent decades, they’ve increasingly become a subject for academic exploration. Works like Spiegelman’s Maus or Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home have been landmarks in gaining broader recognition for comics as an art form with aesthetic and intellectual ambition, and comics’ expanding influence in pop culture has drawn attention to the ways they have long provided a mirror – sometimes a fun-house mirror – for society as a whole.

Today CUNY faculty and staff are engaged with comics in a sometimes surprising variety of ways. This May 7 and 8, comics creators will take center stage at the CUNY Graduate Center, as the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies (CLAGS) hosts “Queers and Comics,” a conference bringing together LGBT comics writers, artists and scholars.

Keynote speakers at Queers and Comics will be Alison Bechdel and Howard Cruse. Bechdel’s success with Fun Home was preceded by more than 20 years of work on the alt-weekly comic strip “Dykes to Watch Out For.” A musical based on Fun Home, originally produced at the Public Theater in 2013, is about to open on Broadway. Cruse is best known for his graphic novel Stuck Rubber Baby, a tale of sexuality, homophobia, racism and resistance in the US South during the 1960s. Tony Kushner described the book as “deeply important and fortifying” and called Cruse “one of the most talented artists ever to work in the form” in his introduction to the book when it was first published in 1995.

CLAGS board member André Carrington, an organizer of the conference, says it will offer a forum for LGBT cartoonists, comics writers and artists to discuss their art, help document the past and present of queer comics, and provide a place for professional discussions.

“The idea for the conference came to CLAGS about two years ago from Jen Camper, who’s a cartoonist who’s worked on a number of comics,” Carrington told Clarion. Camper is the conference’s coordinator, and in that a role she draws on “the strength of her longtime connections with LGBT cartoonists,” he noted. There will be approximately 110 panelists, comprising about 25 to 30 panels. Topics to be covered include histories of queer comics, the visibility of transgender people in imagined worlds, and examinations of how queer comics reflect and critique queer culture, Carrington said.

In addition to Bechdel and Cruse, the conference will also feature queer comics creators Ginkoru Tagame, Jiro Ghianni and Ivan Velez, who was only the second Latino writer to have worked for Marvel Comics.

The conference is open to the public, and much of it, including the keynotes, will be live-streamed. “We want a broad audience, because this is a fantastic occasion for people to learn about the subject,” Carrington said.

Interest in comics as a medium for telling important stories is not limited to people like Spiegelman, Bechdel or Cruse who’d been making comics for years. When civil rights legend John Lewis, the former head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who has served in the House of Representatives since 1986, decided to write a memoir, he chose to do it as a graphic novel, titled March. Lewis has worked with cowriter Andrew Aydin and comics artist Nate Powell to develop his narrative in graphic form. The first volume (of three) was widely acclaimed and soon became a best-seller. The second volume has just been published, and the book is already in widespread classroom use.

March “is a good example of the central role that comic books have played historically in American culture,” says Ann Matsuuchi, an associate professor in the library department at LaGuardia Community College. Lewis chose to write his memoir as a comic, she says, in part because a 1958 comic book about Martin Luther King and the Montgomery bus boycott had “served to inspire him as a young man.”

Eight months ago, Matsuuchi was one of several organizers of a symposium at the Graduate Center, “Comics @ CUNY,” that explored comics as a subject for scholarship and a teaching tool.

“This is new territory for both teaching and scholarly research,” Matsuuchi told Clarion. “The varieties of comic books, graphic novels, manga/manhwa are wide-ranging and present narratives and imagery in so many innovative ways.”

Topics explored at the symposium included how comics have both shaped and reflected struggles over social power and cultural norms. “Mainstream and popular superhero characters such as Wonder Woman – who was originally created by a Harvard psychologist – can provide worthwhile insight into a history of American feminism. Several books about this character have been published in the last two years, including one from an academic press,” notes Matsuuchi, who has written about Wonder Woman herself.

Presenters at Comics @ CUNY included Jonathan Gray, associate professor of English at John Jay. Gray recently founded the Journal of Comics & Culture with Pace University Press; the first issue is due out this fall.

Author of Civil Rights in the White Literary Imagination, Gray is working on a book project for Columbia University Press titled Illustrating the Race, which examines representations of blackness in US comics since the first appearance of the Marvel character Black Panther in 1966.

In a presentation last year at the New School, Gray discussed how blackness is often portrayed as alien, and explored why black superheroes are often depicted as cybernetic hybrids, half human and half machine. “Given that people of African descent were often linked to primitivism, in the cultural imagination in general and in comic strips and early comic books in particular, do these post-human black heroes induce us to understand both race and heroism differently?” Gray wrote.

Depicting Race

“It’s a fairly common trope – there’s Cyborg, there’s Deathlok, there’s Hardware, who was part of the Milestone comic line as well, and Misty Knight,” Gray said in an interview this April. “I’m still working through why this is so common. This is actually the most common heroic trope for black people” in US comics.

One black superhero who doesn’t fit into that template is Luke Cage, a Marvel character Gray says has changed over time – and not for the better. “The original Luke Cage has been badly misunderstood. People say he’s an imitation of Shaft, but that’s because [Shaft] was the big cultural thing at the moment” that the Luke Cage character first saw print, in 1972. “More accurately, Luke Cage is based on Attica.”

“The No. 1 thing in the news [at the time] was the Attica prison riots and the death of George Jackson,” Gray told Clarion. “Attica was front page news for months in New York. The original Luke Cage is, in part, a response to the Attica prison riots, as seen through this ridiculous cartoon glass that is Marvel Comics.” Cage acquires his superpowers while imprisoned for a crime he did not commit; his name puts an unsubtle spotlight on that origin story.

By the 21st century, Gray says, Luke Cage “has been updated and rehabilitated…in a way that I find sadly predictable,” with a cleaned-up Cage now a leader of the Marvel superhero group the Avengers. “So he’s a leader, sure,” says Gray, “but he’s not a transgressive figure, the way he was in the ’70s, when he was an ex-con who was fighting to clear his name and contesting the state.”

Crime, the courts and justice are themes that Staci Strobl and Nickie Phillips explore in their magisterial work, Comic Book Crime: Truth, Justice, and the American Way. Published in 2013, the book illustrates how comic books have presented crime since the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Strobl, an associate professor of law and police science at John Jay, and Phillips, associate professor of sociology and criminal justice at St. Francis College, analyzed around 200 comic books that appeared from 2001 to 2010 in their research.

Crime and Justice

Crime is of course a perennial subject in comics and graphic novels; Phillips wrote last year that their book examines “how stories in comic books frequently explore ideas of authority and power post-9/11, as well as how cultural notions of retributive justice resonate in the books.” A close look at “how mainstream comic books envision heroes and villains” illuminates “powerful ideological messages about what motivates crime,” Phillips contends.

While there are important exceptions, Strobl said in an interview this April, overall the comics industry “follows some very steadfast conventions that have led to the most prevalent portrayals of crimefighters being white males who protect women and children against massively apocalyptic threats, with or without aliens and zombies, that necessitate some pretty extreme responses and retributive rhetoric.” Comics, and the books and TV shows based upon them, are an important source of American ideological identity, Strobl says. The messages they reproduce, she adds, suggest that “the political problem of a punitive criminal justice system is also potentially a problem of the imagination.”

“Nickie and I began this work as graduate students in criminal justice at CUNY,” Strobl recalls. “We had trouble finding a research advisor, and a couple of professors told us that we should probably stay away from this type of pursuit as intellectually dubious. So we became our own advisors and began presenting at conferences. Luckily we were discovered by sociologists Jeff Ferrell and Mark Hamm, who saw something in what we were doing and encouraged us to aim higher and write a book.”

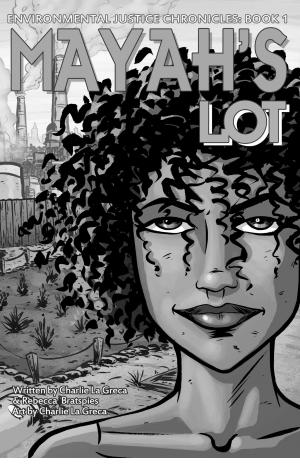

CUNY faculty are exploring comics not only as an object of study, but also as a pedagogical tool. Rebecca Bratspies is a professor at the CUNY School of Law and founding director of the CUNY Center for Urban Environmental Reform (CUER). As part of CUER’s work in youth education on environmental justice, Bratspies wrote a comic book, Mayah’s Lot, in collaboration with famed comic book artist Charlie La Greca, who also did the book’s art. Mayah’s Lot tells the fictional story of a local resident – Mayah – as she discovers that a private company (Green Solutions) is planning to turn a local lot into a toxic waste facility. The comic goes into plenty of detail and paints a vivid picture of local organizing on environmental justice issues.

Mayah’s Lot is envisioned as the first in a series. “We’re in the final stages of the second comic,” Bratspies said in an interview. “It’ll be released over the summer.” Like the first book, she says, “it serves as a how-to guide for people who want to organize on these issues.”

Bratspies says she’s pleased by the reception the first book’s received. In use in public-school classrooms and distributed through state environmental agencies, she says it’s proven a valuable teaching tool. “When I teach it in New York City public schools, I ask students if they live in an environment; lots of times they say no, because they don’t see [the term] as being about themselves and their lives. That’s what we’re trying to change.”

Steve Ovadia, a professor in the library department at LaGuardia who was an organizer of the Comics @ CUNY symposium, says that meeting sparked his own interest in comics’ pedagogical possibilities. “I’ve become more interested in them as a teaching tool,” said Ovadia. “My LaGuardia colleague Stafford Gregoire spoke extensively about this during our event and it was an aspect I hadn’t really considered prior to his talk.”

Explaining Tech

Ovadia writes the blog My Linux Rig, a personal project on a topic that is close to his heart – and he thinks comics have some untapped potential for teaching about computers. “Comics are definitely an intriguing way to introduce computer science and technological concepts,” he said. “One of the most famous Ruby programming manuals is a comic – Why’s (Poignant) Guide to Ruby. And for Linux, a solid comic might make it more accessible to less technically inclined users. The strength of comics is that it presents visual ideas with text, and that’s a fairly standard way of teaching technical concepts.”

Douglas Rushkoff, a professor of media studies at Queens College, is known for writing deep theory about computer-based media. He’s also written comic books.

Rushkoff, who joined the CUNY faculty late last year, has written three comics: Testament, A.D.D., and Club Zero-G. Science fiction writer and journalist Cory Doctorow, co-editor of the tech culture blog Boing Boing, describes A.D.D. as a “tight, action-packed comic wrapped around a serious, thought-provoking critique of the commodification of youth culture.”

Theory and History

“I write each thing I do very specifically for a particular medium,” Rushkoff told Clarion this spring. “I usually start with an idea that is specific to a form. Testament, my graphic novel about the Bible as a kind of narrative time machine, was invented for comics.” In contrast, he says, his book Present Shock “is a literary nonfiction treatment of time. It’s an extended meditation that would not be particularly friendly to sequential narrative.”

Rapid changes in how we communicate are changing the kinds of stories that are told, Rushkoff says: “I am teaching a course in narrative – Interactive Narrative Lab. And there, we look at how traditional narrative is threatened – appropriately! – by interactive media from comics to apps, and how that changes power relationships and politics.”

Rushkoff says that comics can be an effective vehicle not only for telling stories, but also for considering theory: “Brooke Gladstone’s book on propaganda, The Influencing Machine, is quite effective and a great classroom comic book. It’s not necessarily any easier than reading an essay, but students are often fooled into thinking comics are easier…so I use it.”

One of the best analyses of the specific power of the comics form is itself a comic, he adds, citing Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud. “Understanding Comics is pretty profound all by itself,” he told Clarion. “You can’t come to recognize the deep functioning of one medium without applying those insights to all the others. I think people who read that comic are changed forever.”

For Josh Brown, executive director of the American Social History Project at the Graduate Center, his relationship to comics has particularly personal roots. “My father was an artist. He made his living as a cartoonist, and he was not always thrilled about it. When I was a kid, he was doing crime comics, before the comics code. I certainly was thrilled that he was doing this kind of work!”

Crime comics were a prime target of the 1950s psychologist and anti-comics crusader Fredric Wertham, who warned that these lurid tales would warp young minds. In a kind of natural experiment, albeit with a very limited data set, Josh Brown does not seem to have suffered much from this youthful exposure.

As a child, Brown says, “I ended up always drawing.” A native New Yorker, he went to Music & Art High School (now LaGuardia High School of the Arts), and in graduate school he paid his bills doing fabric design, as well as freelance mural painting and illustration. He also did posters, buttons and leaflet illustrations for antiwar movements. But all this was entirely separate from his academic work as a doctoral student in history.

“When I was in grad school I didn’t talk about cartooning,” he said in a recent interview. “It probably would have been the kiss of death at Columbia at the time.” And it was some time into his development as a social historian before he became interested in visual culture as an academic subject. “My early work was on working-class gangs in New York in the 19th century, as well as those in Philadelphia and Baltimore. But I didn’t use any visual evidence at all.”

It was only when he began working on a documentary film project at the American Social History Project that his frame of reference changed. “I began looking at the illustrated press of the 19th century, and realized there was a lot more there. That eventually became my dissertation and a book.”

Since then the visual culture of the 1800s has become the main focus of Brown’s scholarship. With support from a Guggenheim fellowship, Brown has been working on his next book, The Divided Eye, which examines the visual culture of the US Civil War.

Over the years Brown had worked on various comics projects, mainly personal efforts he did on the side. These included an independent comic on Ed Koch and a long-running blog of political cartoons, Life During Wartime, that was a way to speak out during the Iraq War. He did a short graphic novel, Robeson in Spain, as a project with the Archives of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and contributed a chapter to a comics history of SDS.

With a recent project, a 2013 online graphic novel titled Ithaca, Brown’s comics work and his historical scholarship came together in a new way. It’s a tale of a murder, set during the sharp conflicts of Reconstruction in the wake of the Civil War. “I always thought that Reconstruction was an era ripe for telling dramatic stories,” said Brown, “and they could be told well in a graphic form.” (This and other comics by Brown can be found through his website.)

Somewhat to his own surprise, Brown says, “I’m finding that my cartooning and scholarship seem to be merging more than I might’ve thought possible. So I definitely want to explore this some more.”

It’s not what he would have expected when he began his doctoral studies, Brown says with a laugh. “It’s still somewhat amazing to me that now you can enroll in an art program and major in graphic novels.”

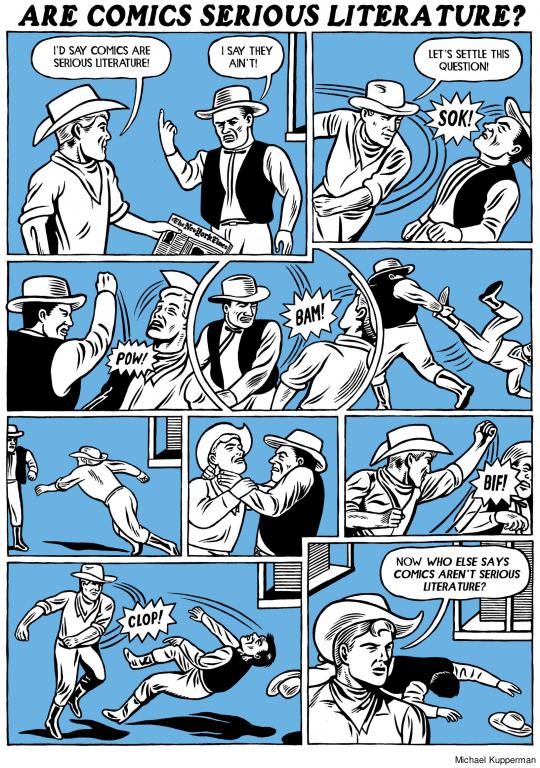

As Brown implies, the idea of comics having a place in the academy still encounters some reflexive resistance. Comic books? is the implicit or explicit question. Do you really think that comic books deserve serious discussion in a university classroom? Of course, in 1860 most college professors might’ve said the same thing about Charles Dickens.

It’s hard to say what role comics may play in the university in another 10 or 20 years. What seems clear is that academics are more engaged with comics than ever before, and that shift does not seem likely to end any time soon.