It was the summer of 1964 – nearly 50 years ago – when about a thousand civil rights activists went down to Mississippi for Freedom Summer.

During Spring semester, Queens College students involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) were working to recruit volunteers. In an effort dubbed Freedom Week, they organized speakers and fundraisers with the goal of supporting a summer campaign to register African Americans to vote and teach classes in “Freedom Schools” in Mississippi, then one of the most disenfranchised states in the union.

|

The Summer’s Beginnings

Barbara Omolade, then a senior at Queens College, sat at one of the recruitment tables. She recalls Freedom Week as having a visible, but small presence on campus at the beginning – much like many organizing campaigns today. It was during this week in April 1964 that an anthropology student named Andrew Goodman signed up for Freedom Summer.

“He was a regular student and what he did was extra brave,” said Omolade, who years later was a faculty member at CCNY’s Center for Worker Education. “Everybody was aware that Mississippi was dangerous. People had been killed. Medgar Evers had been murdered [in Jackson, Mississippi] the year before.”

That June, at the beginning of the campaign, Goodman and two other civil rights workers, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, did not return from a trip to investigate a church burning. While federal officials searched for the three missing men, other volunteers continued the movement’s work. The bodies of the three men were not discovered until August; investigators learned they had been lynched by members of the Ku Klux Klan. James Chaney was an African American civil rights worker from Mississippi; New Yorker Michael Schwerner had been working in Mississippi as a CORE field worker since the beginning of 1964; his wife, Rita Schwerner, was a Queens College student.

From Apathy to Activism

Outside the Queens College Rosenthal Library, the Chaney-Goodman-Schwerner Clock Tower stands as a memorial to the lives and work of the three young activists. Inside the library, documents chronicling the movement and the summer of 1964 are part of the Queens College Civil Rights Movement Archive, now six years old. The collection includes many fragments of history, donated mainly by QC alumni: Essays of Freedom School students on “What does freedom mean to me?”; letters home about a civil rights workers’ daily routines; an activist sign-in sheet with Andrew Goodman’s signature.

Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were just three of the many thousands who took part in the civil rights movement’s campaigns despite threats of violence. Among the students who came from up north to support the fight waged by African Americans in the South, Queens College was well represented.

Longtime SNCC worker Dorothy Zellner graduated from Queens College in January 1960. Zellner was an editor at the campus paper, The Crown. Decades later, she returned to Queens to work on press and publications at the CUNY School of Law. Zellner recalls Queens College in her student years as pretty apathetic.

“Compared to City College, it was dead as a doornail,” said Zellner. “But there must have been things percolating.”

Months after graduation, she went down to Miami to participate in a sit-in organized by CORE. For her, that marked the start of nearly 20 years of living and working in the civil rights movement in the South. By 1964, through SNCC, Zellner was recruiting students from Northeastern colleges to go to Mississippi that summer. After organizing in the South for a couple of years – getting arrested, being pulled over and patted down by police for no reason, being knocked on the head by a cop – Zellner knew that this would not be just a summer trip.

“We were very concerned about divas and nutcases,” said Zellner. “We wanted people who had respect for the black community, who would not do something crazy like wearing shorts to church. We didn’t want prima donnas who said, ‘Oh okay, I’ll do this, but I won’t do that.’”

Mark Levy, Queens College ’64, remembers talking to Zellner about Freedom Summer while traveling on a commercial bus line between Massachusetts and New York. Levy had been reluctant to join other campaigns, but the way Zellner talked about Freedom Summer was different.

“[She] talked about it not as a bunch of white freedom riders going down South, but as a request by local Mississippians to ‘Come on down and help us,’” said Levy. “So we were not going down as missionaries. It was something that I could say ‘Yes’ to.”

The Queens College that Mark Levy attended was far from apathetic. In 1961, Levy recalls, the majority of students boycotted classes to protest a speaker ban that had blocked Communist Party Secretary Benjamin Davis, Malcolm X and William F. Buckley from addressing students.

Campus Activity

Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Queens College ’63, was one of the students who participated in the strike, which according to the college’s student newspaper involved 70% of the student body.

“I’ll never forget. My speech teacher was going to have a test that day and I thought, ‘Oh well, I’ll fail this,’” said Terborg-Penn. But she did not join the walkout alone. “It turns out that for a class of 35 students, only three students showed up.”

Terborg-Penn, who was one of the roughly hundred African-American students on campus at the time, recalls that there were no black professors when she first came to the college in 1959. When she graduated in 1963, there were three. Today Terborg-Penn, professor emerita of history at Morgan State, is a leading scholar of African American women’s history.

Terborg-Penn was a member of the campus chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In the early ’60s, the group organized an ongoing picket outside of a Manhattan Woolworth’s in solidarity with Southern sit-ins against segregation. In August 1963, the group traveled to DC for the March on Washington on a bus chartered by QC’s student government.

In the months before the historic march, close to 20 Queens College students traveled south to Prince Edward County in Virginia, where schools had been shut down in defiance of Brown v. Board of Education, to support the work of black churches in organizing their own classes.

“A lot of them did have the idea of saving black students in Virginia,” Terborg-Penn told Clarion. “I raised the question in the [NAACP] meeting. You’re going to send all these people, and they’re going to be in culture shock if they don’t live in a diverse community. They’re going to have problems.”

As training for the Virginia project, Terborg-Penn helped organize a tutoring program at her family’s church, St. Albans Congregational Church in Jamaica, Queens. The following year, a number of activists from Queens College took part in Freedom Summer.

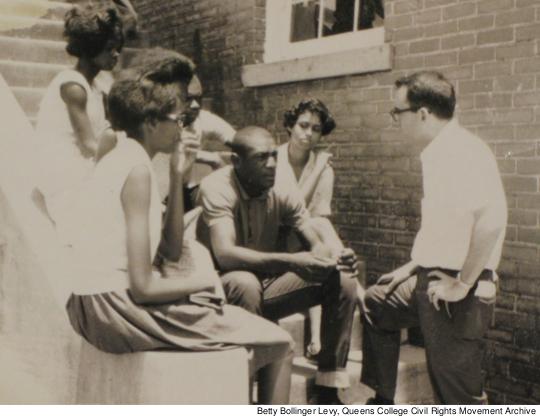

In the summer of 1964, Mark Levy and his former wife Betty Bollinger were among about ten current or former Queens College students who volunteered for the campaign in Mississippi. Their assignment was to teach at a Freedom School set up in a Baptist seminary in Meridian, Mississippi.

“The essence of the school was to ask questions…. What’s this world we want to make? And how do we go about changing the world?” said Levy. “None of us had absolute answers. We were discussing those questions with six-year-olds, eight-year-olds, 16-year-olds, and then 80-year-olds. It was very exciting.”

While Levy and Bollinger were in training in Ohio, the news broke that James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner had gone missing on June 21. Those still training, Levy recalls, felt strongly that they had “to keep on, keep on,” despite the risks.

Michael Schwerner’s brother, Steven Schwerner, was working in the Queens College counseling department at the time. “After the news came out, everybody I knew and people that I didn’t know rallied around me at Queens College,” Schwerner said. Their support was welcome, he recalls: “I felt like I wasn’t walking alone and being stared at. I was walking on campus and people were concerned.”

National Action

Rita Schwerner, Michael’s wife, was a Queens College student. In a statement to the press when the three men’s bodies were discovered, she put their deaths in sharp perspective: “It is only because my husband and Andrew Goodman were white that the national alarm has been sounded.”

Her words were born out by federal investigators: the search for Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman also unearthed the bodies of eight black Mississippians. They included Charles Eddie Moore, a student who had been expelled from college for taking part in civil rights protests, and 14-year-old Herbert Oarsby, who had been wearing a CORE T-shirt. None of eight men’s disappearances had attracted more than local attention. “The people who killed them have never been prosecuted,” Steven Schwerner noted in 2005.

But the national attention did help build the movement, spurring others to take action across the country. In one of many examples, seven Queens College students went on a fast on campus during the July 4 weekend, to raise awareness and money for the movement in Mississippi. That same week, the national reaction to the murders was seen as a significant factor in passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Levy came back to Queens College to teach in the SEEK program, from 1968-73. Like many Freedom Summer volunteers, he went on to become a lifelong activist, in his case working in the labor movement. Over the years, he says, he kept running into people connected to Queens College who had been active in the civil rights struggle. In 2008, he donated things he had saved from the movement to the college library, and that donation became a push to establish the school’s civil rights archives. The archives now include around 35 collections, about 20 of them donated by alumni.

The QC volunteers saved things from daily life, often things that might have been thrown away by someone living in Mississippi. The student essays, the letters home, the incident reports, the Polaroids give a glimpse of their everyday experiences, while also revealing interior lives during a period of intensive self-reflection.

Ben Alexander, head of QC’s special collections and archives, says the materials capture “what happened when the television cameras were off and no one was looking.”

The archive has grown to include donations from others with little prior connection to Queens College. The family of SNCC activist James Forman donated his books and other documents, in part because they wanted them to have a home at a public university. (Forman’s personal papers are at the Library of Congress.) Another Freedom Summer volunteer, Susan Nichols, recently donated items that had been hidden in her closet in Montana. These included phone logs of various movement field offices in the hours immediately after Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner had disappeared. (These documents and other documents can be viewed in the QC library this fall.)

Coming Together

|

Norka Blackman-Richards, assistant director of Queens College’s SEEK Program, uses the archive in teaching her English 162 class. She says students get excited by what they learn.

“They had no clue about Freedom Summer. They had no clue that students around their age went down South into these dangerous conditions,” Blackman-Richards said. “They’re completely floored by the races coming together for this cause.”

Dean Savage, a professor of sociology at QC, has also donated materials to the archive. Savage went to Orangeburg, South Carolina, in 1965 to register black voters. At the time, he was busy with his graduate studies at Columbia University. “Even though I didn’t have time,” he said, “once there was an invitation, I felt that I had to go.”

Savage’s materials recreate certain moments from his time in the South: transcripts of speeches given by civil rights leaders in Atlanta; press clippings about arrests in an Orangeburg sit-in; a snapshot of a Klansman walking past a burning cross at an openly announced Klan rally.

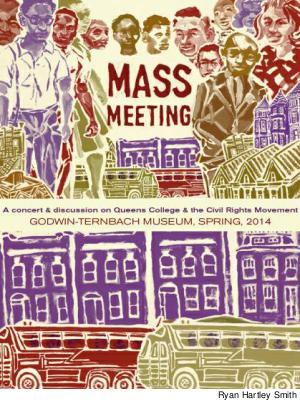

Ryan Hartley Smith, an adjunct lecturer at QC in graphic design, asks his students to take these pamphlets, buttons and photos from the past and relate them to today. In one of his classes, students went to the archive to choose an image or a slogan from the 1960s to relate to a current issue.

Smith’s students showcased their work in an event billed as a “Mass Meeting,” this spring. The students’ images were projected on a screen, people sang freedom songs and students listened to a panel discussion of activists involved in current and past struggles for equal rights.

The event was one of a series at QC this year, coordinated by Levy as part of a Civil Rights Anniversary Initiative sponsored by the college president’s office, and which included discussions on how to teach about the civil rights movement and a special advance screening of the PBS documentary Freedom Summer, which airs nationally on June 24.

Deeper Understanding

At the “Mass Meeting” event, one of Smith’s former students, Richard Ortega, moderated the panel discussion. Ortega, a graphic design major, has also spent time working with the archive. He says he’s gained a fuller understanding of the movement. “It’s not just something in the history books,” he said. “It feels real.”

“In our own way, at Queens College, we try to make a difference,” added Ortega, who is involved in organizing for LGBT and immigrant rights. “What I learned from talking to all these activists is that nothing happens overnight.”