At its June meeting the CUNY Board of Trustees will consider a resolution on “Creating an Efficient Transfer System,” the text of which can be found online at cuny.edu/pathways. That resolution is objectionable both substantively and procedurally: substantively, because it will drastically reduce the quality of general education at CUNY; and procedurally, because it will wrest control over curriculum away from faculty at the campuses and pull it up to 80th Street, where the faculty’s voice will be only one among many. There has been little or no rank-and-file faculty involvement in developing this proposal.

The Board intends to amend its bylaws in June as well, and one of the changes sheds light on who CUNY administration thinks should make decisions on curriculum. Section 8.6, which now states that “the faculty shall be responsible…for the formulation of policy relating to…curriculum,” would instead say that “the faculty makes policy recommendations” on curriculum and related matters.

Eightieth street is pushing the Board of Trustees to move rapidly to make CUNY a very different place. We write in the hope that faculty, once apprised of the Board’s intentions, will speak loudly and effectively in opposition. Nothing less than the future of our University is at stake.

NON SEQUITUR

Anyone who interacts with and cares about our students knows that we make life much too difficult for those who transfer. We need an efficient transfer system, and we needed it yesterday. Policies and procedures for transferring general education credits are among the many obstacles our transfer students face; by all means let us reform those policies and procedures, along with all of the others that make transferring too hard at CUNY. But let us make sure that any changes we adopt will actually help solve the problem, and will not undermine CUNY’s existing strengths.

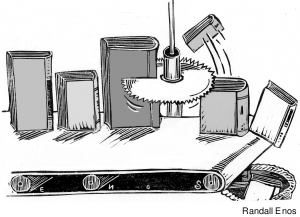

The second sentence of the resolution’s Rationale states the obvious truth that in order to “enhance [transfer] students’ progress, CUNY must insure that its transfer system operates smoothly and efficiently.” But then there appears a non sequitur that runs through the rest of the resolution, shifting its focus from outdated and unwieldy processes to curriculum. Under the inspiring banner of transfer reform, this resolution launches a focused attack on general education itself.

The proposal calls for the formation of a task force, to be charged with “creating a common general education framework for the undergraduate colleges of the University. The framework will set credit requirements in general education across broad disciplinary areas and will consist of a maximum of 36 credits of lower-division general education courses, with baccalaureate programs able to add up to six credits of lower- or upper-division credits at their option.”

The proposal calls for the formation of a task force, to be charged with “creating a common general education framework for the undergraduate colleges of the University. The framework will set credit requirements in general education across broad disciplinary areas and will consist of a maximum of 36 credits of lower-division general education courses, with baccalaureate programs able to add up to six credits of lower- or upper-division credits at their option.”

Such a reduction in the number of general education credits would require arbitrarily eliminating valuable and carefully developed courses, and thereby dilute academic standards.

For these reasons, resolutions in opposition to this proposal have already been adopted by governance bodies at Baruch, Brooklyn, City, College of Staten Island, and Lehman; by many departments at Brooklyn College; by several CUNY-wide discipline councils; and by student governance bodies at Baruch and Brooklyn. Another, even more disturbing, reason is that the homogeneity of this framework would sweep away many of the best features of the colleges’ general education programs, which have been carefully shaped by faculty in order to serve our students’ needs and aspirations. Unique and valuable initiatives developed by a college’s faculty to help their particular students, such as Brooklyn’s Core Curriculum or BMCC’s health education requirement, have no place in CUNY’s proposal.

RUSHED

We encourage everyone who reads this article to spend some time with the resolution itself, and the critiques of it by various faculty bodies. This framework will lead to deep and sweeping changes in general education curricula at all of our campuses. One would expect that a framework with such momentous implications would be formulated with most deliberate care. The task force to be created at the June Trustees meeting, however, is to deliver its report to the Chancellor by November 1, 2011. The blueprint for general education at CUNY is to be torn up and replaced in less than half a year. A process this rushed will not have a good outcome, and many of the faculty resolutions ask the administration to slow it down.

This task force represents a radical change of approach, not just to general education, but also to faculty governance and, in particular, faculty control over curriculum. One might expect that the scale of the changes in curriculum and in faculty governance that this resolution would usher in, and the precipitate haste with which they will be enacted, would have very compelling justifications. But those offered to date fall far short of the appropriate standard of proof.

The actions proposed in this resolution find their main justifications in a report issued by CUNY in October 2010, entitled “Improving Student Transfer at CUNY.” This 30-page report (excluding appendices) purports to be a close, data-driven analysis of the challenges facing the transfer system(s) at CUNY. But as an analysis by Baruch Professor of Finance Terrence Martell shows, much of the data cited in the report is not what it seems, and very little of it lends any support whatsoever to the proposition of a University-wide overhaul of general education.

CUNY’s report seems largely motivated by the claim that “excess” credits – those earned by students beyond the 120-credit minimum for graduation with a baccalaureate degree – represent a cost to the University of $72.6 million. But as Professor Martell points out, at most, $20.9 million of that might be attributable to problems with CUNY’s transfer system. Either way, we vigorously reject the suggestion that general education is a luxury we cannot afford to give our students.

Another source of data for CUNY’s report is a set of three focus groups of transfer students who graduated with more than 120 credits. These students suggested a number of reasons for having earned more than the required number of credits, according to the report: “having changed majors…needing to take more courses to bring up their GPA’s…extra courses so they could maintain full-time status to remain eligible for [health insurance or financial aid],” in addition to problems with transfer and course evaluation. But the lesson CUNY’s report draws is that “students had not acquired these credits through a simple desire to explore academic byways.” Instead, it concludes that “when they changed majors, it was usually because they had trouble meeting requirements – especially math requirements – in their first [majors].”

As Professor Martell says, “The Report strongly suggests that all our transfer students change majors because they cannot succeed at their initial choice! This is not our experience and it demeans our transfer students.” Indeed, CUNY’s report imagines a status quo in which none of our students (transfer or otherwise) ever experience intellectual growth or curiosity. This flies in the face both of the mission of any university and of the daily experiences of CUNY’s faculty and students.

STUDENT VOICES

The students in these focus groups identify a number of problems with which all of us are familiar – the need for students to maintain full-time status; the insufficient offering of required courses; gaps in academic preparation. But the recommendations made in the report appear not to engage these problems at all – and may even exacerbate them. CUNY’s modest proposal to reduce the amount of general education we can offer our students may indeed make graduation arrive more quickly and easily for many of our students. But what of the value of their diplomas, their ability to contribute to the economic growth of the city, and their prospects for a fulfilling life?

Anyone who has worked with transfer students at CUNY knows that the transfer system is not just inefficient, but in many respects simply broken. A task force comprising students, faculty and administrators is an excellent mechanism for identifying and cutting through the many administrative and operational knots that constitute this complex problem. Put the focus of the resolution on transfer, where it belongs, and not on general education, and the overall approach is not a bad one. Our objection is not to a task force in which these groups collaborate, and certainly not to the aggressive pursuit of a solution to the very real problems our transfer students face. It is only when such a task force intervenes in curricular matters that it becomes objectionable.

TIME TO ACT

When we recall that in June the Board will be asked to amend the bylaws so that faculty no longer set, but only recommend, policy on curriculum, we see that the resolution on general education is part of a larger assault on faculty governance, and a major step in the creation of a more top-down university, with much reduced academic standards. If you agree, the time to act is now. If your department, and the governance body at your college, have not yet adopted a resolution in opposition to this proposal, urge them to do so right away, and to forward it to the University Faculty Senate, which is collecting such resolutions and passing them on to the administration. Add your own name to the online petition.

The administration would like us to believe that these damaging changes are inevitable. They are not, unless we allow them to be.

______________________________

Matthew Moore and Scott Dexter are faculty members at Brooklyn College. Moore is chair of the philosophy department; Dexter is a professor of computer and information science and director of BC’s Core Curriculum.

______________________________

TO CLARION READERS: What Do You Think?