|

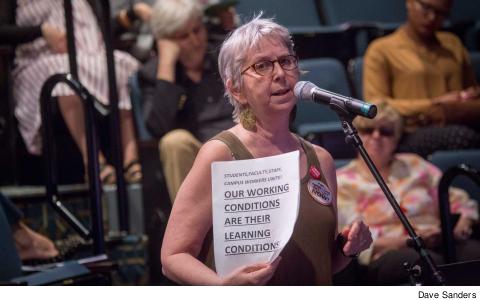

CUNY faculty members and PSC officers attended a CUNY Board of Trustees hearing on June 18 at Hostos Community College to testify about the need for more state investment in CUNY. Members raised the issue of staggeringly low adjunct pay and the need for the recently passed “maintenance of effort” bill.

The PSC action at the BOT in June is just the latest in several union demonstrations regarding the underfunding of CUNY. In April dozens of adjuncts, as well as full-time PSC members, went to Albany to demand that lawmakers support the call for $7K, the campaign to increase adjunct pay to $7,000 per course, and PSC members also testified on the issue before the City Council and at previous BOT hearings. For the PSC, bringing adjunct pay at CUNY in line with what adjuncts earn at other peer institutions is not just an economic necessity for part-time PSC members, but a critical correction to the underpayment of adjuncts that shortchanges students and undermines CUNY’s educational mission.

Below are statements from PSC member testimonies in June.

A ZERO SUM?

CUNY seems to always accept the terms imposed by the state of a zero – sum game. A win in one area means a loss in another. Despite claims to care deeply about the students, the board and the chancellery seem to care more deeply about whether they will offend Governor Cuomo, who has never expressed a deep understanding or concern about CUNY. He has consistently opposed the union’s efforts to support a maintenance of effort bill and increase the amount of state investment to hire many more full-time faculty.

The PSC’s vision was one that would have included adequate funding for full-time replacement lines, some of which would go to qualified long-serving adjuncts. Instead, provosts and presidents are having to make choices that diminish rather than expand academic services: the availability of computers, space, and courses for students and the investment in professional development for faculty and staff are just some of the cuts that are being considered. Hints are given to the chairs that maybe there will be less money available for sabbaticals or travel money.

The university boasts about its reputation as a center for research, yet faculty who had been awarded time to do research now find that reassigned time received in the past is being challenged by administrators. Rather than using the three-credit reduction to enhance time to do research, it is being used to reduce it. Similarly, there is an expectation that time given out for departmental and college responsibilities will also be reduced. I hope that the BOT is clear that we will recommend that faculty not perform these responsibilities if their reassigned time is withdrawn.

Lorraine Cohen

LaGuardia Community College

HIGH RENT, LOW PAY

Let’s just look at rents. The average monthly rent for a one-bedroom in Staten Island is $1,500; Bronx is $1,600; Queens is $2,100; Brooklyn is $2,400; Manhattan is $3,100. The average monthly rent for the five boroughs for a one-bedroom is $2,140.

Contrast these rents with four upstate New York cities where there are SUNY colleges. The average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Binghamton is $700; in Albany it is $1,000; in Buffalo and New Paltz it is $1,100. The rent in those four cities for a one-bedroom apartment averages out to $975 per month. Over a one-year period, the difference in average rent for a one-bedroom between upstate and New York City amounts to $14,560.

Or New York City rents for a one-bedroom are 120 percent higher on average than upstate.

Mayor Ed Koch once said that one week’s salary for one month’s rent is what New Yorkers ought to be paying – or 25 percent of one’s earnings. Right now, a CUNY adjunct teaching three CUNY courses pays two-thirds of her salary on rent for a one-bedroom apartment. Often, to compensate for the nine-credit limit at any one campus, CUNY adjuncts also teach at other colleges and universities in the New York City area. This promotes a lessening of identification of CUNY adjuncts with any one college.

If we don’t achieve our contract demand for $7,000 a course, the stressful financial and psychological circumstances that many of CUNY’s over 14,000 adjuncts endure will deepen as rents in New York City continue to rise at a rate faster than adjunct salaries.

Anthony Gronowicz

Borough of Manhattan Community College

|

CUNY: STAY TRUE

I spent many years of my life working as an organizer and advocate for low-wage workers who struggled to make ends meet and often joined together with their coworkers for a living wage and just working conditions.

I am presently a doctoral student in sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center, have taught as an adjunct lecturer at the Murphy Institute and Hunter College, and will begin as a Humanities Alliance Teaching Fellow at LaGuardia Community College in the Fall. I, like other talented, dedicated, hardworking adjunct faculty at CUNY, am now also a low-wage worker joining together with my coworkers for a living wage and just working conditions.

The annual pay for the average adjunct lecturer teaching a full load of eight courses at CUNY is $28,000. This is about $20,000 less than the yearly income of $48,000 required for a modest-yet-adequate standard of living for even a single person without children in my borough of Brooklyn, according to the Economic Policy Institute. CUNY’s low adjunct pay is even 50 percent less than comparable public university systems in our neighboring states of New Jersey and Connecticut. This is unconscionable.

I call on the Board of Trustees to do everything in its power to fulfill the stated mission espoused on its website and subway advertising to foster upward mobility while serving the children of the whole people within the city of New York. It cannot be true to this mission while providing poverty-level compensation to the dedicated faculty teaching the majority of its undergraduate courses.

Lynne Turner

Murphy Institute, Hunter College

TAKING ON OTHER JOBS

These bags of paper represent the workload an adjunct carries day to day. And as the semester progresses, the workload gets heavier. Not only paper grading – the list of job duties is multifarious: answering emails, creating lesson plans, completing student progress reporting, posting material on Facebook, posting grades on Facebook, posting grades on CUNYfirst, writing recommendation letters, organizing class trips outside of campus, attending class trips outside of campus, studying approaches to pedagogy, solving student dilemmas, volunteering time to help students prepare for big project or big tests – the list goes on! Adjuncts deserve 7K for the work they do.

Imagine going to a job where you know 10-20 hours of your hard work and effort is not being compensated, and yet you still do the job without any qualms. In fact, you put more effort into this job because you know that there are 30 or more people depending on your efforts, and yet you struggle to make end meet. You are two months late on paying your rent and you earn – as I did in 2017 – around $19,000. I have held various jobs in my life, from construction to sales, restaurant work to working on the set of Law and Order SVU. Never have I worked as hard as when I have been an adjunct professor – and yet never have I been compensated so meagerly.

We should ask ourselves if it is really fair to work and not be paid for the work you do, and does underpaying adjuncts have a negative impact on our students’ quality of education?

Last year, when one of my classes was cut at the last minute, I had to find other employment. I worked at a non-profit where I manage a building used for artistic events. I had to clean bathrooms, change toilet paper, empty garbage and mop floors. One day I saw a former student, she saw me mopping a floor. For a moment, I saw a perplexed look on her face, and while I shouldn’t have felt embarrassed because work is work, I did.

She looked at my mop, she looked at the shiny floor, and my sweaty face and she said, “Professor?”

Camillo Almonacid

Hostos Community College

CAN’T SURVIVE

As an adjunct, I typically work for at least three colleges simultaneously. It is the only way I can make ends meet and even then it is difficult, especially in the face of rising costs for everything else. When I get the amount of classes I need, I am in a continuous state of exhaustion. It is practically impossible to stay up to date on the grading, incorporate new teaching methods, and keep up to date in my field. I simply have little to no time to work with students who are struggling. I love teaching and I love working with the students. It devastates me when I can’t give the time needed to students who need me the most.

Summer time is an especially difficult period. I have little to no income from CUNY and the other school for which I teach simply does not pay enough to make up the difference. I end up having to live on credit cards and so go deeper into debt with every passing year. This is a time when I should be working on my own research and writing, but instead I battle daily with depression and despair. Currently, I cannot pay my bills or my rent. It is exceedingly difficult to focus on intellectual pursuits when I’m worrying about how I can afford to live. By the time the fall semester starts, I will be in a state of desperation. It is very difficult keeping that out of the classroom.

Marga Ryersbach

Queensborough Community College