In this summer of protest, African Americans have taken to the streets with a simple but ambitious demand: “Treat us like human beings.”

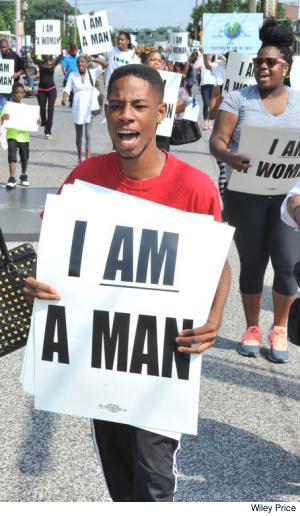

In Ferguson, Missouri, marchers held placards that reprised the 1960s slogan, “I AM a MAN” (now with the addition of “I AM a WOMAN”). In this town where police fired ten shots at an unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown and struck him six times, apparently while his hands were up, a homemade sign said, “Don’t shoot! Black men are people, too!” Others carried signs insisting that “Black lives matter.”

On Staten Island, those protesting the chokehold killing of Eric Garner by a white City cop voiced the same theme. “The reason I’m marching is because it’s time for people of color to be recognized as human beings,” 63-year-old Shirley Evans told the Daily News. “For years and years, we’ve been fighting for our rights. It’s time we’re seen as equals.”

|

A human being has the right to not be gunned down by the police for “blocking traffic,” and then be left in the rotting sun for four hours. A human being has the right to not be choked to death for “resisting arrest” for allegedly selling loose cigarettes – despite repeated pleas that he can’t breathe.

But other basic rights are also required to sustain human life – like access to water. When Detroit’s Dept. of Water and Sewage systematically shut off the water of more than 125,000 of its poorest residents – some of whom owed as little as $150 on their bills – the UN found that the shutoffs were a basic violation of human rights.

“These are my fellow human beings,” Detroiter Renla Session told the Detroit News. “If they threatened to cut off water to an animal shelter, you would see thousands of people out here. It’s senseless….They just treat people like their lives mean nothing here in Detroit, and I’m tired of it.”

Meanwhile, Detroit businesses still had access to clean water, despite the fact that 55% of those businesses have past-due water bills The corporate debtors included the Chrysler Group, real estate firms and a golf-course management company that owed nearly half a million dollars, but businesses were not included when the shut-offs began. This is in keeping with Mitt Romney’s famous comment – in an echo of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling – that “corporations are people.” But apparently not all people are people.

The denial of black humanity takes many forms. A police officer in a nearby town declared that the Ferguson protesters “should be put down like a rabid dog.” Another suburban cop, on duty in Ferguson during the protests, pointed his rifle in protesters’ faces and yelled, “I will fucking kill you.” After both incidents received news coverage, the two men were obliged to leave their jobs – but these and similar incidents raise questions about the institutional culture they reflect.

Certainly in Ferguson, those protesting Brown’s killing were treated by the police force as an inhumane entity en masse. The use of armored vehicles, tear gas, plastic bullets, threatening tactics and unconstitutional arrests sent a clear message: if you express your anger and your grief, you put your freedom – and maybe your life – at risk. The freedom of speech that the Supreme Court has guaranteed to corporations and the wealthy was not extended to them.

Ferguson’s black residents live in fear of the police in part because the police force has 50 white officers and three black ones, patrolling a community where 67% of the residents are black. Not surprisingly, blacks make up 86% of police stops, according to a racial profiling report from Missouri’s attorney general.

These inequalities highlight the fact that the Mike Brown or Eric Garner killings aren’t just caused by the individual bigotry or hot temper of one “bad apple” cop. They reflect structural inequities that run deep throughout US society and history.

Four miles south of Ferguson is the burial place of Dred Scott, the slave who in 1857 sued for his freedom and lost. He lies in Calvary Cemetery on West Florissant Avenue – the same street that, in Ferguson, has been the center of protests since Mike Brown was killed. In rejecting Scott’s claim to freedom, the US Supreme Court’s Chief Justice wrote, “A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a ‘citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States.” Lest we forget, African Americans’ slave ancestors were described in the US Constitution as “three-fifths” of a person.

One hundred fifty-seven years after Dred Scott lost his case, and 156 years after his death, the bruising effects of the country’s racist history are evident throughout the structures of American society. That history has shaped institutions that deprive black Americans of the political power to shape their future, or the resources they need to do so.

Ferguson and Detroit are both places where a largely black community is run by a white power structure. In Detroit, Republican Governor Rick Snyder appointed Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr to replace elected officials; a new white mayor, Mike Duggan, now runs the city with an emphasis on what sociologist Thomas Sugrue calls “trickle-down urbanism,” a focus on selective gentrification that excludes jobs for working-class residents.

In Ferguson, the police chief is white, the mayor is white, and five of the six city council members are white. Moreover, the district where Michael Brown attended high school, in which students are almost entirely black, is controlled by a white out-of-state Republican.

Unequal political power perpetuates unequal access to resources. The largely poor and black residents of Ferguson and Detroit both contend with shrinking city services that impede daily life, abysmal job prospects, punitive social-welfare policies, and under-funded school systems. An acute example is the fact that the high school Michael Brown graduated from had only two cap-and-gowns sets for its graduates, who had to take turns wearing them to pose for graduation pictures.

Detroit has been subject to public disinvestment for decades. The water shutoff this summer was the culmination of decades of statewide cuts in public spending, a consequence of anti-tax politics that were significantly fueled by racial animus. From Reagan’s fables about “welfare queens” and Cadillacs to Lee Atwater’s infamous “Willie Horton” ad, white resentments and fear have been used for decades to consolidate a policy of shrinking the public budget. As was dramatically clear when Katrina hit New Orleans, it’s a policy that hurts African Americans the most, even as it injures the public as a whole.

As Missouri’s public budget shrinks, the black majority in Ferguson has been obliged to pay for its own oppression. Newsweek has reported that despite Ferguson’s relative poverty, the town’s second-largest revenue source is fines and court fees. Its court issued 24,532 warrants last year, or about three warrants per household. Essentially, the town has been bankrolling itself vis-à-vis racial profiling and harassing black residents with costly tickets, warrants and court fees for such crimes as “driving while black,” so-called jaywalking (as Mike Brown was stopped for) and other trumped-up violations.

The reason communities like Ferguson or Detroit lack the funds to pay for basic needs is not because there is no money. Millions of dollars in Federal resources have been allocated to equip local police forces across the country with military combat gear, often to police largely black communities – a reality on ugly display during Ferguson’s street protests. Yet Detroit’s 688,000 residents have received no Federal aid to avert or recover from its historic bankruptcy filing. As one man on Twitter, who identifies as @YoungMelanin95, tweeted: “They have the money to bring military-grade weapons to a civilian protest, but not enough money to give Detroit access to clean water.”

The attacks on unions in Detroit, public and private, have attacked the ability of black workers to maintain a middle-class income. When I grew up in Detroit in the 1960’s and 1970s, the UAW was still a vigorous union whose strength insured robust wages and benefits for its members. As a result, my father and cousins and uncles made salaries that enabled them to live well – to own homes, support their families, send their children to college, retire without worry. Concessions demanded of the autoworkers’ union disproportionately hurt Detroit’s black residents, and more recent attacks on the wages and pensions of public workers have their own racial edge. Nationally, black workers are 30% more likely to hold public-sector jobs. In majority-black Detroit, the figure is much higher. This year Detroit teachers faced a 10% pay cut until public outcry prompted its emergency manager to reverse course days before the start of the school year.

And so the basic rights of more than ten million underprivileged African Americans are undermined by the limited resources allocated to them: those deemed worthy by a racist society receive the most, those deemed unworthy receive the least – and have the most exacted from them.

That is the backdrop against which, this summer, water was withheld in one place, a life gunned down in the other. No wonder that out of frustration and necessity, people in both Detroit and Ferguson – and in solidarity protests across the country – have taken to the streets to demand that their humanity be recognized.

Denial of common humanity has always been fundamental to white supremacy, throughout history. We can draw a direct line from the anti-slavery slogan, “Am I Not A Man And A Brother?” in the 19th century to this summer’s protests (“I AM a Man”) to see the pattern.

A life can be taken by the fast, brutal violence of a police bullet or a chokehold. But there is also the slower violence that can kill you just as dead, more gradually and in pieces – through poor health care, unemployment and bad housing, through denying you the resources you need to live.

From Ferguson to Detroit to Staten Island, this summer’s protests have been a source of hope. But if protesters are to ultimately succeed, we have to remember this: without attacking the systemic racism that has been the feeding ground for dehumanizing black life, we will be here again.

_____________________________

Bridgett Davis is a Detroit native and professor of journalism and creative writing at Baruch College. Her new novel, Into The Go-Slow (Feminist Press, Fall 2014), is set in Lagos and Detroit.