It was the summer of 1975, and Gerald Meyer was spending his days in the reading room of the main branch of the New York Public Library, researching his dissertation on New York’s legendary left-wing congressman Vito Marcantonio. Taking a break one day, Meyer looked at the front page of The New York Times and read some news that would change his life.

|

In response to the City’s fiscal crisis, the Times reported, the Board of Higher Education planned to close two CUNY campuses. Though the colleges were not named, it was clear to Meyer that one would be Hostos Community College, the school where he worked.

When the PSC chapter at Hostos was formed in 1973, Meyer became its first chapter chair. Now quick action was needed, or he would also be its last.

SAVING HOSTOS

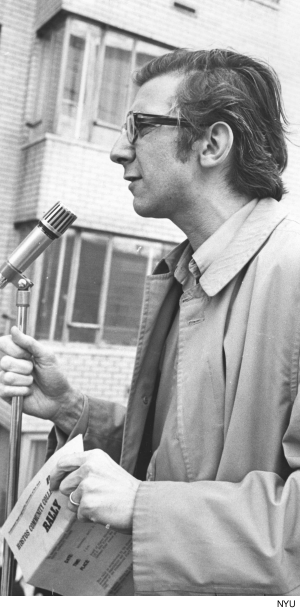

The then-assistant professor of history went to work, reactivating a faculty-student alliance he had helped organize to win additional building space for HCC. Over the next year the Save Hostos Committee petitioned and lobbied, registered new voters, held marches and rallies and sold buttons for $1 apiece to finance its activities. Students occupied the campus for 20 days in an action led by another group, the Community Coalition to Save Hostos. In the end, Hostos survived.

“It was an incredibly intense experience,” Meyer recalls. “People weren’t just fighting for buildings. They were fighting for a college that served the needs of the community.”

Meyer’s passion for Hostos and its students has continued in the decades since. He retired in 2002 but couldn’t stay away, returning in 2004 to teach as an adjunct. This year Meyer donated $25,000 to the college, money that can be used for everything from funding student travel abroad to the school’s lobbying in Albany. He was honored on April 25 when the college named a conference room in the school’s 500 Building after Vito Marcantonio, whose 1989 biography by Meyer is now in its fourth printing.

HISTORIAN

Meyer’s scholarship has been acclaimed for its close examination of an era in New York history that had been ignored after the onset of McCarthyism and the Cold War. “Professor Meyer has been a pioneer in unearthing the history of the vibrant New York political left of the 1930s and 1940s, especially the largely unknown Italian-American left,” Joshua Freeman, professor of history at Queens College and the Graduate Center, told Clarion. “In his work, the streets of East Harlem and the fierce battles over labor and politics come alive.”

Marcantonio was a complex politician with deep local roots, who counted both the Communist Party and the Republican Party among his bases of electoral support. By drawing on extensive correspondence between “Marc” and the voters he represented, Meyer’s biography reveals Marcantonio’s “deep passion for the welfare of his poverty-stricken Italian American, Puerto Rican, and African American constituents, a concern which made his office a model of constituent service and advocacy for the poor,” wrote Pennsylvania State Rep. Mark B. Cohen, a member of the Democratic Leadership Council.

|

Meyer, 72, is also co-editor with Philip Cannistraro of The Lost World of Italian American Radicalism. He has published more than 60 articles, and his historical research continues today. But at the April, 2012 celebration, he was also lauded for his work as a teacher and a mentor to several generations of Hostos students.

“He really is a hero. His heart is with the college,” said Saudy Tejada (HCC 2004), a former student of Meyer who works at a Bronx nonprofit and is an active Hostos alumna. “He understands the struggles of immigrants and other students who could be shut out of the system.”

Meyer grew up in a poor, working-class family that lived in a series of small towns around Hoboken, New Jersey; he was the only one of three brothers to complete high school. “I experienced a lot of deprivation and it was very scarring and really unforgettable,” Meyer said.

His first act of political protest occurred when he was 15. Attending a Catholic school during the McCarthy era, he was confronted by a nun who caught him with a copy of a book by an anti-McCarthy writer and warned the rest of her homeroom class not to speak with Meyer. He threw his books on the floor and walked out of the room, never again to return.

“That was very liberating,” Meyer says today.

Enrolled in a public high school in Weehawken, Meyer volunteered with the 1956 Adlai Stevenson presidential campaign, spoke out against McCarthyism and collected petition signatures from his fellow students calling for the racial integration of their all-white school. Though he is no longer religious, Meyer says his activism was inspired in part by Catholic teachings on social justice and the moral responsibility of the individual to stand for what is right regardless of the consequences. “I think I look upon Left politics as good works,” he says. In the years that followed, Meyer worked on an Israeli kibbutz, took part in Civil Rights-era freedom rides, and organized protests against the Vietnam War, while working and going to school – first as an undergrad at Rutgers, then as a graduate student at City College.

DISENCHANTED

As the 1960s unfolded, Meyer became disenchanted with the countercultural aspects of the New Left and a movement culture that was increasingly alienating to many working-class people. “It just seemed so childlike and counter-productive,” he told Clarion.

Instead, Meyer found himself drawn to the ethos of the Old Left that had flourished in the 1930s and ’40s and that helped elect Marcantonio to seven terms in Congress. In particular, Meyer admired the earlier generation’s commitment to building enduring working-class institutions.

“I had an impulse towards building things, creating structures of some sort or other,” Meyer says.

Meyer found an outlet for his organizing energies when he arrived at Hostos in 1972, following four years teaching as an adjunct (including stints at QCC and KCC in the CUNY system). Hostos had opened in 1970, just after CUNY’s move to open admissions, and was primarily intended to serve New York’s growing Puerto Rican community. It was founded as CUNY’s only bilingual college, and much of the faculty and the student body were politically conscious and socially active.

HOME

“I really had the sense I was home,” Meyer said. “I felt very welcome there from the administration on down. They were very interested in building something that worked, and I was eager and willing to participate in that from the very beginning.”

At the time, the entire college was housed in a refurbished tire factory. The five-story building was crammed with students and faculty and lacked an auditorium, a bookstore, a daycare center or adequate lab space . During the “heroic years” of 1973 to 1978 (as Meyer refers to them), the campus community repeatedly mobilized to procure the resources it needed and to defend its gains.

These days, Meyer laments that Hostos is in danger of being “homogenized into a general CUNY culture” – a trend, he says, that is being exacerbated by the Pathways Initiative. Still, he remains devoted to Hostos and its largely working-class students.

CIRCLE OF 100

In 2006 Meyer helped start the Hostos Circle of 100 Scholarship & Emergency Fund. The Fund has raised almost $200,000 since its founding, distributing both $1,000 scholarships and $500 emergency grants to standout students who are close to graduating but need a final boost.

Meyer sees no contradiction between these charitable donations and being a committed leftist who advocates a reversal of the deep cuts to CUNY’s public funding.

“We need a political solution,” Meyer told Clarion. “But in the meantime you have a student who’s burned out of an apartment, what do you do?” he asks. “You can’t just preach that the system is evil and that at some point there will be a transformation of society.”

“These scholarships are validating experiences for students,” said Tejada, who co-chairs the Hostos Circle of 100 with Meyer. “It increases their confidence to hear people saying, ‘we believe in you.’”

Meyer has also remained active over the years with the PSC chapter. “He has kept practicing the same approach that he and others used when they were able to save Hostos,” says PSC Chapter Chair Lizette Colón. She points to Meyer’s emphasis on coalition-building, both on- and off-campus, as key to the chapter’s effectiveness today. “Jerry’s wise advice has helped me enormously in my role as chapter chair,” says Colón. PSC members also know Meyer for his sense of humor and his attention to “the thoughtful little details which count so much,” she adds.

STILL WORKING

“I get up in the morning, I still have to work,” says Meyer – though he has now been a pensioner for a decade. “He stays very busy,” comments Luis Romero, Meyer’s partner of 34 years. The two registered as domestic partners in 1993, and Romero says that “retirement” has not slowed Jerry down: “He’s not in a rocking chair looking at a sunset.”

Besides his work with the Circle of 100, Meyer teaches a writing intensive course on world history to the year 1500, co-chairs the Behavior Social Science Writer’s Group at Hostos, continues his research on the the culture and history of the Left in America, is active in the campus PSC chapter and is organizing his own extensive files, which he has donated to the Hostos Community College Archives.

“We’re fortunate that Professor Meyer had the good sense as a historian to save this material,” says Matt Flaherty, a reference librarian at Hostos and its assistant archivist. “It’s the cornerstone of our collection. It’s what we build on.”