More than 200 people attended the October 25 PSC forum, “Defending the Social Safety Net.” The article below is adapted from the keynote by Dean Baker, an economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington. The panel also included Kim Phillips-Fein of NYU, James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute, and CUNY’s Frances Fox Piven. (See here for more information.)

The forum took place as Congress’s so-called “Super Committee” considered trillions of dollars in budget cuts, including cuts in Social Security and other safety net programs. The Super Committee’s report is due on November 23; click here and you can send a letter opposing cuts to the safety net.

The PSC’s Social Safety Net Working Group has prepared a brochure about what is at stake in these debates. If you’d like to find out more about the Working Group, contact John Hyland at [email protected].

______________________________

You often hear people in Washington say we need to raise the age for Social Security retirement benefits. We’ve already raised the age for full benefits to 67 – although lot of people don’t know that – and you have politicians and pundits saying, “Let’s raise it to 70.” Most of them are working at desk jobs, and their attitude is, “I love my job, I’m in good shape, I want to work until I’m 70.”

For a lot of people, though, that’s not a reasonable thing to expect. That includes factory workers and construction workers, and also people who are the custodians at CUNY, people who are working in restaurants, or working as a nurse’s assistant or a nurse. Most jobs in this economy, in fact, are not that easy for someone who is well into their 60s.

RICH GET SOFTER

The federal Labor Department keeps statistics on the percentage of people working in physically demanding jobs or difficult working conditions. Not surprisingly, the percentage of people in these jobs varies hugely by income. In the bottom fifth, close to 60% are working in these demanding, difficult jobs. But even in the top fifth, it’s almost 20%.

This is worth remembering in relation to life expectancy. You often hear pundits say, “People are living longer, so let’s raise the retirement age.” But life expectancy also varies by income – and that’s more true today than it was 20 or 30 years ago. As the Congressional Budget Office noted in 2008, “Low-income and low-education groups have seen little gain in life expectancy” in the United States.

So is it fair that someone who debones chickens or cleans floors all day should be forced to work longer because lawyers or Senators have longer lives, and still enjoy their jobs?

We get a lot of misleading talk about budget deficits, how entitlements are supposedly breaking the bank. For the most part this talk is very dishonest, because that is not the real story.

People are being particularly dishonest if they paint this as a Social Security problem, or some general problem of out-of-control public spending. The problem isn’t Social Security, or even “Social Security and Medicare” – the problem is our broken health care system. Fix health care, and you can fix the deficits.

We pay more than twice as much per person as in any other wealthy country. Take your pick – Canada, Germany, whomever you like – we’re paying more than twice as much per person. And we don’t have anything much to show for it: we have the shortest life expectancy of the wealthy countries.

So what would our budget deficits look like if we paid the same amount per person for health care as Canada or Britain? The answer is that we wouldn’t have these huge budget deficits – in fact, we’d start having budget surpluses.

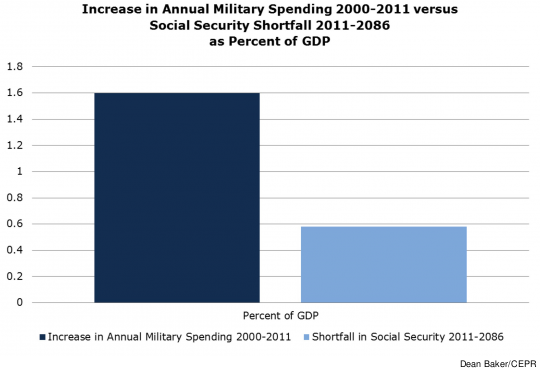

Of course, military spending has also been a big contributor to the deficit. In comparison to recent increases in military spending, the amounts at issue for Social Security are not that large.

|

You hear pundits and politicians yelling that there’s a huge Social Security shortfall – they talk about something like $5 trillion over its 75-year planning horizon. People in Washington like to use trillions of dollars over long periods because they know that sounds really scary, even if no one has any clue what it means.

I had a conversation with an economist once where I asked, “Why are you expressing this as trillions of dollars when you know no one knows what it means? Why don’t you express it as a share of GDP [Gross Domestic Product], because we can all understand percents.” And he said, “If I express it as a share of GDP it doesn’t sound big but we know it is big.” I told him just to flap his arms when he says it. [Laughter]

Now, if you look at the Social Security shortfall as a share of GDP over the next 75 years, it’s a bit less than 6/10ths of a percent of GDP. For comparison, how much did we increase military spending between 2000 and the present as a share of GDP? The answer to that is 1.6%.

MILITARY INCREASE

I’m not talking about the whole military budget, this is just the increase in military spending from 2000 to 2011. It’s almost three times the size of the shortfall in Social Security. That doesn’t mean it’s a small number, so I’m not going to say it’s trivial – but it didn’t bankrupt the economy. Neither would an amount that’s just 1/3rd as large. What I’m saying is that if we solved the projected shortfall in Social Security totally by raising revenue, it would not have a devastating economic impact.

I don’t know how many times I’ve heard people around Washington say, “It’s going to be a long time before jobs come back, we’re just gonna have to tough it out.” Or when they say we should cut Social Security and call it “tough medicine.” Well, the “we” in this sentence is never the people who are going to be unemployed. It’s never the people who will have their income slashed when benefits are cut. The people who say this are doing fine. And they’re not so tough. Let’s keep that in mind when the Super Committee comes out with its report.