|

On April 4, 1968, an assassin robbed us of one of the greatest prophetic voices of the 20th century. Although many people know that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., died in Memphis, many don’t know what he was doing there. They don’t know that he died in a struggle for the right of public workers to have a union.

Throughout his life, King stood up for union rights. His teachings about the rights of labor can serve us well in our own trying times, when those rights are under fresh assault.

One of King’s phrases that we rarely hear is this: “All labor has dignity.” King spoke these words to a mass meeting of over 10,000 people in Memphis on March 18, 1968, in the midst of a strike of 1,300 black sanitation workers. Some 40% of these workers were so poor they received welfare benefits even though they worked 60-hour weeks. Speaking of both sanitation workers in Memphis and the working poor across the country, King said, “You are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages.”

But the strike was not just about pay. “Let it be known everywhere,” King declared, “that along with wages and all of the other securities that you are struggling for, you are also struggling for the right to organize and be recognized.” The key issues for the Memphis strikers were their demands that the City of Memphis grant collective bargaining rights and the collection of union dues – the very two items that Gov. Scott Walker targeted in Wisconsin. Like city officials in Memphis, Walker knows that if you can say no to bargaining rights and dues collection, you can kill the union.

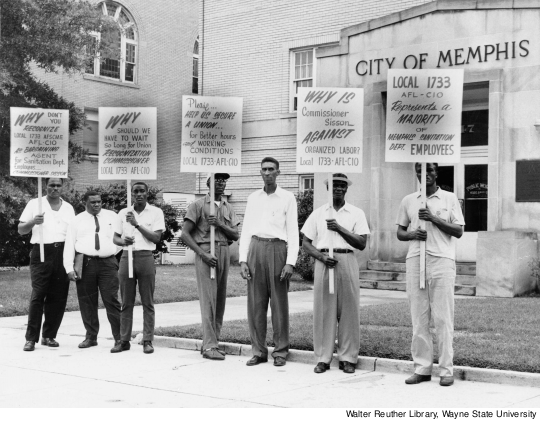

RACE & RIGHTS

The Memphis sanitation workers’ strike was part of the black freedom struggle. Jerry Wurf, national president of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), to which the sanitation workers’ Local 1733 belonged, defined Memphis as “a race conflict and a rights conflict” as well as a union conflict. But white municipal workers had also suffered from local government’s hostility to unions. While many of the city’s white craft workers got paid at union scale, they had no contract. And when white firefighters, teachers and police officers tried to organize unions, the city fired and blacklisted them; city officials did not want organized workers exercising any independence or raising the costs of their labor.

Opposition to public-employee unionism was a strong tradition in Memphis. Sounding like Fox News today, City Councilmember Gwen Awsumb warned in 1968 that the “ultimate destruction of the country could come through the municipal unions.”

Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb III came from a family of anti-union employers. Like Gov. Walker and other Republicans today, he held that public employees should not have the right to collectively bargain over their conditions of work, and said he would never sign a union contract. Like Walker, Loeb wanted to cut public jobs to help end an operating deficit: he wanted sanitation workers to do more work for less pay. If they didn’t like it, they could quit.

The AFSCME union insisted that workers had a moral and constitutional right to act together – to bargain collectively, not just individually. Field organizer P.J. Ciampa, sent in to help, reminded strikers of their rights under both the Thirteenth and First Amendments. “I don’t know of any law in Tennessee that says you have to subject yourself to indentured servitude,” Ciampa told striking sanitation workers. “As a free American citizen you are expressing yourself by saying: ‘I am not working for those stinking wages and conditions.’”

King, who was no stranger to confronting unjust laws and court injunctions, fully supported sanitation workers’ right to collective action. “We can get more organized together than we can apart,” King said in his March 18 speech. “And this is the way we gain power…. What is power? Walter Reuther said once that ‘power is the ability of a labor union like UAW to make the most powerful corporation in the world – General Motors – say yes when it wants to say no.’ And I want you to stick it out so that you will be able to make Mayor Loeb and others say yes, even when they want to say no.”

King’s support for the sanitation workers reflected his long-held concern for economic justice. With some 25 million unemployed and many more underemployed, with 50 million without health insurance and 44 million living in poverty, King’s prophetic words in Memphis ring true today: “Do you know that most of the poor people in our country are working every day? And they are making wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the mainstream of the economic life of our nation.”

ECONOMIC JUSTICE

The second phase of the civil rights movement, King said, would have to be the struggle for “economic equality.” To that end, he came to Memphis as part of his Poor People’s Campaign. He sought to organize a mass movement to demand that Congress shift its priorities from funding military buildup and war to funding jobs, housing, health care, and education. The richest country in the history of the world, he said, could easily afford to eliminate poverty. What it lacked was the will to do it.

In that regard, King reminded strikers and their supporters in Memphis of the story of Dives in the Bible, who went to hell because he passed by the suffering Lazarus every day without ever paying attention to his brother’s plight. “And I come by here to say that…if America does not use her vast resources of wealth to end poverty and make it possible for all God’s children to have the basic necessities of life, she, too, will go to hell.” Today our government and media seem incapable of grasping King’s moral vision – but King emphasized throughout his life that human rights include labor rights.

Republicans today have targeted the very union King helped to build in Memphis. Founded in Wisconsin, AFSCME flowered after King died in the successful fight for union rights in Memphis in 1968. AFSCME became one of the largest unions in the country, with King regarded as an honorary member and practically a founder of the union.

Racial justice is at issue in today’s attacks on public worker unions. Thanks to the destruction of manufacturing jobs and unions, the one toehold many black and minority workers (and especially women among them) still have in the economy is in unionized public employment. Now, the Republicans want to take that away.

The GOP not only wants to eliminate public employee unions but also to pass “right to work” (for less) laws that take away the requirement that workers in unionized jobs pay union dues or their equivalent. Just as it has done throughout the South, this type of law would undermine unions by starving them of funds, while, in King’s words, providing “no rights and no work.”

In King’s framework, killing public employee unions today would be immoral as well as foolish. He said the three evils facing humankind are war, racism and economic injustice. The purpose of a union is to overcome the latter evil, and without them, unions wages and living conditions will go down for a significant number of workers, especially women and workers of color.

UNION POWER

King always saw unionization as a moral as well as a political question. As he told organizers at the Highlander Folk School, “I never intend to adjust myself to the tragic inequalities of an economic system which takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes.”

King’s rhetoric spotlights the central question in today’s budget battles: Who should pay? Today’s public employees have won better wages and conditions than those faced by Memphis sanitation workers 43 years ago. But they still live fairly modest lives – and it was not teachers, firefighters or sanitation workers who caused our nation’s economic and fiscal collapse. Why, then, should they be asked to pay for its cost, instead of the private-sector profiteers who created a gambling casino on Wall Street and left the public to pay the bill? Is that economic justice?

King believed that power concedes nothing without a struggle, and for that reason he long supported union organizing. Indeed, he went beyond that to support other forms of direct action that may be increasingly appropriate today as Republicans try to break the last hold of public employees on a living wage.

In Memphis, King called for a general strike in support of the sanitation workers’ demands. “You may have to escalate the struggle a bit,” he told his audience. “If they keep refusing, and they will not recognize the union, and will not agree for the check-off for the collection of dues, I tell you what you ought to do, and you are together here enough to do it: in a few days you ought to get together and just have a general work stoppage in the city of Memphis.”

FIGHTING ON

King’s audience responded with thunderous applause and cheers, because they knew that African Americans did so much of the city’s work. If teachers, sanitation workers, students, and workers across the board went on strike they could definitely shut the city down.

King said, “All labor has dignity.” There is no more important time than the present for us to remember his words and to follow King’s lead in fighting for union rights as human rights. In the wake of the anti-union assault and pro-union protests in Wisconsin and other Midwestern states, let us reflect on where King would have stood in that fight were he alive today.

My bet is that he would be in the streets, fighting for the rights of workers.

______________________

Michael Honey, Haley Professor of Humanities at the University of Washington, Tacoma, is editor of All Labor Has Dignity (Beacon Press, 2011), a collection of King’s speeches on labor, and author of Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign (W.W. Norton, 2007).