On October 17, the CUNY Board of Trustees held its first in-person hearing since the pandemic began. At this hearing at the Graduate Center, PSC members addressed issues being raised in the union’s upcoming contract campaign.

Speaking directly to the trustees and the chancellor, members spoke about low pay and high workloads for part-time and graduate student instructors, highlighting how this exploitative employment is detrimental to undergraduate education. Full-time faculty spoke about how the historic underfunding of CUNY has led to a shortage of faculty for core college courses and an inability to hire enough full-time tenure-track faculty.

UNIFIED MESSAGE

While the union has had numerous in-person demonstrations and marches since the pandemic began, members have not, until this October, had the chance to address the chancellor and the trustees face-to-face – literally – to tell them how CUNY is falling short in its mission and what the university can do to change that.

Union members delivered a unified message stating that the Board of Trustees and CUNY Central both have a responsibility to push for the full funding of CUNY in the upcoming state and city budget negotiations. The push would be a win for students and their education. More money could be used to upgrade campus infrastructure and full funding for CUNY would raise the prospects of securing a contract with CUNY that includes fair raises for faculty and staff.

Below are excerpts from some of the testimonies delivered at the meeting. They have been edited for print publication.

Grads exploited

So much of CUNY’s functioning hinges on graduate students, who are, by and large, some of the system’s most precarious workers. During their careers, Graduate Center [GC] workers like me are sent out to CUNY’s various campuses to teach students and assist professors. We are the lifeblood that circulates through the entire system, ensuring its functioning and interconnection. Often in our teaching assignments, we are the first educators

Zoe Hu, PSC chapter chair at the Graduate Center, testifies about the exploitation

of graduate workers. (Credit: Erik McGregor)

that under graduates encounter, because the majority of our students are freshmen and sophomores. For these students, we are the face of CUNY and what CUNY has to offer them.

And yet we are unable to do our work because our livelihoods are deteriorating. A recent study of graduate student wages and stipends found that, adjusted for cost of living, the GC’s English department, where I study, ranks second to bottom in income. This ranking is within the entire United States, meaning that compared to all other English PhDs in the country, the English department at GC is the second-to-worst department in terms of an attendee’s standard of living. Added together, my stipend and wages are around $28,000 a year, pretax. The average rent in Brooklyn right now is $3,000. It is a simple fact of math that one cannot survive in New York City on GC pay alone, even as one performs full-time Graduate Center work.

Furthermore, as an English PhD student I am lucky, because English is the rare department within the GC where all graduate students are fully funded. Other GC PhDs have no stipend funding at all and are taking on two or three part-time jobs in addition to their teaching loads. It is easy to imagine what all of this does to our work as educators and researchers.

Many graduate workers try extremely hard for their students, but they are still too overtaxed, too tired and not paid nearly enough. They are teaching 50 students in a room and being paid nothing for some of that work, because nonteaching hours – during which we grade, offer feedback and do some of the most important aspects of educational labor – are often unremunerated. The work suffers, and so do the students.

Meanwhile, next door at NYU and Columbia, where graduate students recently went on strike, graduate workers make an average of $45,000 a year. The salary at Rutgers, a public university in a state where cost of living is lower, is $43,000. That CUNY pays its grad workers what it does is an embarrassment. It is an embarrassment for what is supposed to be one of the greatest public university systems in the country. And it means that prospective graduate students, many of whom do get accepted to the schools I mentioned, are no longer even considering CUNY as an option.

I went to CUNY because, as I said, I believe in its values and mission. But everywhere I look, it feels as if my colleagues are barely able to sustain themselves. They are taking seven, eight years to complete their PhDs. They are juggling multiple jobs. They are grading on subways. And the entire university is greatly disadvantaged because of it. As graduate workers, we deserve not just a livable wage but a fair wage. It is time that CUNY leadership does the right thing, not just for us, but for the system as a whole.

Zoe Hu

PSC Chapter Chair

The Graduate Center

Hiring crisis

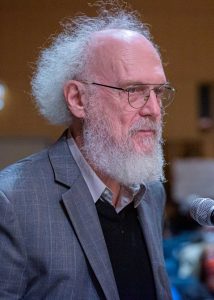

There is a crisis in faculty hiring. Although I have been retired for four years, I was asked as an adjunct to teach physical chemistry, the third-to-fourth year course I had taught for most of the 52 years I taught at City College [CCNY]. Another course for seniors and master’s students, inorganic chemistry, is still not assigned; a faculty member could be assigned, at the cost of finding someone else for the more difficult task of teaching the

Michael Green, retired CCNY professor (Credit: Erik McGregor)

introductory course, and an adjunct is being sought at this time.

The central problem is obvious: The CCNY chemistry department has not been allowed to hire since 2015. There have been several retirements since then, including mine. The faculty shortage has become critical. If for some reason it were only this department, then it should be possible to cure the problem with a couple of hires. However, as far as I know, the problem is more general. If the problem is as general as it appears to be, the entire college, at least, and possibly the entire university, is at risk.

While I am not aware of the reason for the hiring block, as far as I can see, the college, and perhaps the university, is being strangled. It no longer matters what the reason is, but there must be a cure quickly. It is not appropriate to be seeking adjuncts at the last moment for advanced courses. In such a case, it is impossible to guarantee the quality of the instruction. I understand CCNY is to be allowed a grand total of eight tenure-track hires, which probably does not cover retirements for a year. Lecturers are [an insufficient] answer, as they do not fully participate in the department.

Michael Green

Professor, Chemistry, retired

The City College of New York

Capital needs

We are excited about the life science hub that will house the Hunter College School of Nursing and the Hunter College School of Health Professions and look forward to the many opportunities created by bringing together multiple institutions. However, our concern is that many faculty, staff and students are barely hanging on in crumbling and dangerous working and learning conditions. At Hunter College, my alma mater, the biology and chemistry departments have a challenging time retaining faculty because of the state of their facilities. Some of our colleagues have left. For years, the faculty and staff have been hoping construction would resume at the building on 74th Street as set out in CUNY’s master plan. Again, we were hopeful after fighting hard to get more resources from Albany.

Brooklyn College is another campus with severe infrastructure needs. Poorly maintained labs have negatively affected the recruitment of grad students in the biology department, and it was reported that a professor wears a helmet in case tiles fall from the ceiling in Boylan Hall. I, too, share my colleague’s fear, because while teaching at the Brooklyn Educational Opportunity Center [BEOC], a projector screen came loose and it hit my hand. Luckily, I was not seriously injured.

Another issue I would like to bring to your attention is the mold found on campuses. Bronx Community College, City Tech and the BEOC are three campuses where mold was found. This is unacceptable. I find that the administration does not remediate the issue properly because why is the mold reappearing? Also, there needs to be transparency on how the issue is being remediated.

I am here to say that our teaching conditions and students’ learning conditions are in dire need of repairs. The state of CUNY’s infrastructure sends a message that we are not valued. Faculty, staff and students do not feel safe. Look at the many social media feeds that document the crumbling infrastructure of CUNY.

Increasing CUNY’s capital budget in next year’s budget request is essential to mediate the backlog of major repairs needed at our university’s buildings, many of which are more than 50 years old. More funding is essential to retaining and recruiting future faculty, staff and students to the people’s university.

Felicia Wharton

PSC Treasurer

Professors needed

The rate at which the university is hiring lecturers at the expense of professors is alarming. The proportions established this year, with the $53 million in new funds for full-time faculty, are not sustainable. CUNY’s budget request indicated an intention to hire 500 professors, 500 lecturers and 75 nonteaching research professors. But, in fact, only 30% of the funding designated for full-time faculty went to professorial hires, $16 million out of $53 million. That decision permitted the university to authorize only 120 professorial searches, as compared with 475 lecturer searches. If the university continues to appoint only one professor for every four lecturers, CUNY will not maintain a research-active faculty, which is critical for serving our students, our disciplines and the public.

CUNY lost 383 full-time faculty to retirement and attrition over the past five semesters, the vast majority of them professors. The 120 new professorial appointments won’t begin to backfill that loss, not to mention the massive deficit in professorial lines that occurred over the previous decade, dating back to the recession of 2008.

There is an important place for lecturers, and the PSC supports lecturer searches as a path for our highly qualified adjuncts to full-time employment. At the current rate, however, CUNY will give the appearance of addressing the full-time faculty shortage, but will eviscerate the scholarly and research capacity of academic departments. With $53 million in recurring annual funds, the university should have hired more than 120 professors universitywide. It must do better going forward.

James Davis

PSC President

Published: November 21, 2022 | Last Modified: November 30, 2022