|

When President Barack Obama announced a plan in 2013 to have the Department of Education rate colleges and universities by a “bang for the buck” measurement that was heavily weighted toward institutions with the lowest rate of tuition increase, the plan met with resistance from college administrators and faculty alike – especially those at public institutions of higher learning. The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) was a leading force of opposition to the proposed ratings system, due in part to the system’s failure to take into account the austerity measures that are taking their toll on public colleges and universities.

The PSC weighed in early against the Obama proposal. As one in a small group of AFT leaders, PSC President Barbara Bowen met with Secretary of Education Arne Duncan to voice those concerns. At the January 2014 meeting in Washington, DC, Bowen argued strongly against the proposed ranking system, which she described as a false solution to the real problem: systematic public disinvestment in higher education.

“Thirty percent of funding for public universities and colleges has been withdrawn over the last 25 years; the proposed ranking system pretends that the way to remedy the loss is to rate colleges on measures that are certain to disadvantage colleges already most disadvantaged,” she told the education secretary. “The only serious solution is to use federal influence and funding to restore state support.”

Now the president and his administration appear to be backing away from the original ratings plan, which would have rewarded, with federal aid, colleges best able to cap tuition increases and speed time to graduation – a scheme that clearly would have placed most public institutions at a disadvantage in the ratings. A new plan put forward by the Department of Education is designed to offer prospective students a range of tools for determining the best institution of higher learning for them.

Flawed Metrics

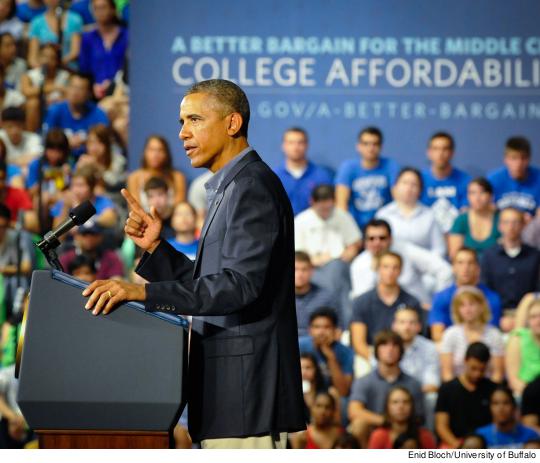

“Colleges that keep their tuition down and are providing high-quality education are the ones that are going to see their taxpayer money going up,” Obama told a packed arena at the University of Buffalo in 2013.

But opponents of the plan asked how public colleges can keep tuition down when state governments systematically reduce public funding. The AFT, PSC and many others opposed the plan because of its flawed metrics and failure to address public disinvestment in higher education. In particular, they objected to the proposal to grade institutions on the rate of tuition increases and the number of years students take to graduate, because of built-in limits on public institutions’ ability to change such outcomes.

Tuition costs at public colleges and universities are largely controlled by state and municipal budgets, not simply college administrators. Between 2008 and 2013, according to the Campaign for the Future of Higher Education, in which the PSC is active, “state funding for higher education as a percentage of state personal income declined by 22.6 percent.”

The criticism appears to have been effective. In June, the Washington Post reported that the administration abandoned its original ratings plan in favor of an approach that offered prospective students a range of tools for evaluating which college best fits their needs and interests. The department’s new plan for constructing metrics for evaluating college and universities aims to provide a larger array of data more relevant to informing student choices, as well as a more complex and inclusive rating scheme that it says will be built to describe schools’ levels of success or failure in meeting various goals set by the department.

Notably removed from the plan is a government-sanctioned listing of “best to worst” institutional classifications along the lines of the annual U.S. News & World Report “Best colleges” feature.

The administration’s original plan “use[d] a single metric – cost – to determine a college’s worth, ignoring important issues and factors, including intellectual and academic strength; cultural, ethnic and racial diversity; and student support services and commitment,” says Stephen Brier, professor in urban education at the CUNY Graduate Center. “This is especially important in schools that draw a heavily urban student population that may have real academic deficiencies because of poor public schooling.”

Contingent Aid

The U.S. News list ghettoizes certain institutions of higher education by marginalizing and stigmatizing schools that heavily enroll minority and low-income students. The Obama administration’s original plan threatened to exacerbate the existing stratification of colleges and universities. But this dynamic would be altered if the factors on which the original plan zeroed in are examined in context. Take, for example, the factor of the time a student takes to graduate from the date of enrollment. Low-income students, who comprise the majority who study at many public higher education institutions, are far more likely to have their education disrupted for economic and other reasons.

But Obama’s original plan wasn’t just any ranking system. It had the federal government’s imprimatur, with its ratings attached to its purse strings. The original plan, for instance, proposed tying the size of a student’s Pell grant to the rating given to the institution the student attended, regardless of whether the college’s rating was the result of diminished public funding.

Consumer Model

Equally important, the variables used to measure the effectiveness of an institution would have distorted the ratings by failing to assess, for example, the academic preparedness of its students. The plan also would have held educational institutions accountable for specific student outcomes without providing the public funding necessary to achieve such outcomes.

There is also the matter of whether higher education should be treated as simply another cash transaction, rated like a marketplace goods-and-services exchange. Even in its most benign form, this approach to higher ed contributes to the corporate model of education, which treats students more like customers than active learners.

Meanwhile, in public systems such as CUNY, faculty salaries stagnate, tenure-track positions disappear and underpaid, unprotected adjuncts pick up an increasing portion of the teaching workload, even as top-level administrators reap corporate-level payouts. These trends undermine the capacity of public higher education institutions to meet federally imposed goals.

The Campaign for the Future of Higher Education, a coalition of more than 60 academic unions (including the PSC), faculty associations and advocates for public education, was both direct and blunt regarding the capacity of the Obama plan to address the present crises of public higher education:

“President Obama’s plan endorses proposals that, at best, tinker around the edges of the problem and could have hugely negative consequences for students and for the future of higher education. In the absence of a mandate for increased investment, the president’s proposal to reduce time to graduation is likely to promote a cheapened curriculum. This is hardly a formula for increasing American competitiveness during an era of intensified global competition.”

Inviting Scrutiny

How the DOE plans to measure success in its revised plan will continue to invite scrutiny. Comparisons between elite colleges sitting on billion-dollar endowments and cash-strapped public universities are intrinsically unfair. Private colleges can often pick from the top of high school graduating classes; public institutions of higher education have statutory admission standards, which may include admitting students who enter college without adequate preparation.

To its credit, the DOE seemed to recognize the shortcomings of a ranking system in light of the many variables necessarily in play, even as it invited public comment on the president’s proposal. The new plan, according to the Department of Education website, will feature “easy-to-use tools that will provide students with more data than ever before to compare college costs and outcomes.” Some of the tools will feature data that has never before been published, promises Jamienne Studley, deputy under secretary of education and acting assistant secretary for postsecondary education, in a post on the department’s website.

The DOE also introduced its latest ratings system idea with a statement that suggests a greater appreciation for the complexity of assessing institutions of higher education: “For many reasons – including the desire for simplicity of the ratings system, institutional autonomy and differences, and lack of shared approaches and data – it seems preferable at this time to concentrate on the core data elements,” which it listed as “excel[ling] at enrolling students from all backgrounds, focus[ing] on maintaining affordability, and succeed[ing] at helping all students graduate.”

Still, the structure of the ratings system and its inherent fairness remains to be seen in the variables it chooses – relative to starved public institutions – to use or ignore. With no funding for increased maintenance costs, and the lack of a contract for faculty over the last six years, CUNY colleges could find themselves at a disadvantage in any ratings system, but still be the best bet for students coming from the working class, as its many successful graduates can attest.

Clarion contacted the Department of Education to address many of the issues surrounding the administration’s initial plan and the criticism leveled against the policy by faculty and administrators. A response was still pending as of press time.

______________________________

Dave Saldana is an award-winning journalist, attorney and labor activist, as well as a former university adjunct.