In The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, Jeanne Theoharis, professor of political science at Brooklyn College, takes a closer look at a legendary figure. The book “argues that the romanticized, children’s-book story of a meek seamstress with aching feet who just happened into history in a moment of uncalculated resistance is pure mythology,” wrote New York Times columnist Charles Blow.

While scholars may know that Parks was already an activist at the time of the Montgomery bus boycott, the political roots of her early life, and her long years of political activity in Detroit, have received less attention. In the discussion below, Theoharis talks about the long life of Rosa Parks.

__________________________

|

Q: A large proportion of Parks’ personal papers have not been made available to scholars. How did that affect your work on this book?

A: Parks gave a portion of her papers to Wayne State’s Reuther Library in the late 1970s but the rest of her papers have sat in a storage facility here in New York for the past five years, unseen by scholars or students. Guernsey’s Auctioneers, charged by the Michigan Probate Court to sell Rosa Parks’ effects (her papers along with material effects such as dresses, hats, eyeglasses, her sewing basket, etc.), has not allowed any scholar to evaluate the papers in that archive. This is a significant loss, not only to my research, but to scholars and students more broadly. It’s hard to imagine auctioning a portion of Martin Luther King’s papers without a scholar assessing what was there.

To work around this restriction, I scoured other archives – Parks’ papers at Wayne State; the NAACP Papers at the Library of Congress; the Highlander Folk School Papers; James Haskins’ notes and interviews with Parks for her autobiography; research by Preston Valien, a Fisk sociologist who sent an interracial team of researchers to Montgomery in the first months of the bus boycott; and many more collections. I read dozens of interviews and oral histories, combed the black press and conducted scores of my own interviews with her friends, family and political comrades. These varied threads helped me piece together a fuller account of her political beliefs and activities.

Q: It’s a shock to learn that before your book, there was no full-length scholarly monograph on Parks, despite the many children’s books about her. Was it this omission that led you to write the book?

A: I found it shocking; I still do. It seemed like a tremendous oversight – and reflective of the very myths I critique in the book. Rosa Parks is one of the most famous Americans of the twentieth century – yet she is treated not as a substantive political figure, but as a character in a children’s book. The only book about her for adults was Douglas Brinkley’s small, un-footnoted Penguin Lives biography. I think people mistakenly assume we knew all there is to know about her.

For me, as a scholar of the civil rights movement in the North, her life in Detroit was particularly compelling. While some historians have started to examine Parks’ political life before the boycott, and the rich story of the origins and maintenance of the Montgomery bus boycott itself, the Detroit part of her history – this half-century of activism in Motown – was completely overlooked.

Q: The title of one of your chapters refers to “The Suffering of Rosa Parks” – her economic struggles, the constant hate attacks, her endurance of hardship in the wake of the bus boycott. Was it difficult to write about those years?

A: Yes, this is a very painful chapter. Despite the fact that Parks has been celebrated for her courage and service, the impact her arrest had on her family and the decade of suffering that ensued is not usually part of the story. She didn’t like to talk about it – and the economic retaliation that civil rights activists faced has often gone unrecognized.

Parks’ arrest had grave consequences for her family’s health and economic well-being. After her arrest, the Parks home received a steady stream of hate calls and death threats, such that her mother talked on the phone for hours to keep the line busy. Parks and her husband lost their jobs and didn’t find economic stability for nearly ten years. Even as she made fundraising appearances for the movement across the country, Parks and her family were at times nearly destitute. She developed painful stomach ulcers and a heart condition, and suffered from chronic insomnia. Her husband, Raymond, unnerved by the relentless harassment and death threats, began drinking heavily and suffered a nervous breakdown.

Eight months after the boycott ended, they left Montgomery for Detroit, but things did not get much better. Prompted by pushes from Parks’ friends and allies, the black press eventually exposed the depth of Parks’ financial need, culminating in JET magazine’s July 1960 story on “the bus boycott’s forgotten woman,” leading civil rights groups to finally provide some assistance.

Interestingly, we also haven’t grappled with how much and how long civil rights activists like Rosa Parks were red-baited and demonized, in the South and the North. In 1957 the Georgia Commission on Education published a broadside, titled Highlander Folk School: Communist Training School, filled with photos of civil rights activists who attended conferences at Highlander, which offered workshops for union and community activists. Five of the pictures show Rosa Parks, who is identified as “the central figure in the agitation which resulted in the Montgomery Bus Boycott.” Over a million copies of the pamphlet were circulated by 1959. One of these photos, featuring Martin Luther King with Parks plainly visible at his side, was plastered on billboards throughout the South, under the screaming headline, “Martin Luther King At Communist Training School.” When John Conyers hired Parks in 1965, the office received a lot of hate mail and threatening calls: writers warned that she “hovered with top communists,” called her a “dastardly” traitor, and told Parks and her new employer that she was not wanted in the North.

Q: Your book examines gender inequities within the civil rights movement. Do you think this is the main reason that Parks’ contributions were downplayed?

A: I think it’s a combination of gender, class and personality. At the first mass meeting in Montgomery, Parks does not speak – despite a standing ovation and calls for her to do so. At the 1963 March on Washington, women were very much relegated to the background. No women got to speak. Parks was dismayed by the treatment of women at the March. Indeed, at the March itself, Lena Horne and Gloria Richardson took reporters aside, telling them that the real story was Rosa Parks and they should be interviewing her. The two got sent back to their hotel before the March was over – and Richardson attributes this to their outspokenness.

Parks also never got to go to college, and many civil rights organizations only wanted to hire college-educated people. Finally, she was a shy person who did not seek out the limelight. With all the attention paid to her role in the Montgomery bus boycott, she actively sought to keep the spotlight off herself in the following decades.

Q: What was her relationship to the labor movement?

A: Parks had a longstanding relationship to labor justice. In the 1940s and 1950s, she assisted her friend and fellow activist E.D. Nixon in his work with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. During the boycott, she came to Detroit on the invitation of Local 600, a militant UAW local, over the objections of UAW president Walter Reuther. She corresponded with the National Negro Labor Council that year and many other labor militants over the course of her life. Once she moved to Detroit, she continued this relationship with Local 600 and other grassroots labor activists – and these allies were some of her most vociferous advocates and supporters when the Parks family hit hard times in 1959-1960. Parks took part in many strike rallies and picket lines throughout her life, from striking Greyhound workers in DC to sanitation workers in Memphis to newspaper workers in Detroit.

Q: You talk about her “rebellious life.” Why has Rosa Parks so rarely been seen as a lifelong rebel and activist?

A: Rosa Parks’ politics were far more expansive and progressive than most people understand. Her political roots began with her grandfather, who was a supporter of Marcus Garvey, as he sits out on their porch with his shotgun ready to protect their family from the Klan violence that had escalated after World War I. (“I wanted to see him kill a Ku Kluxer,” Parks said years later.) Her adult political life begins as a newlywed with her husband Raymond Parks (who she describes as “the first real activist I ever met”), who is working to free the nine Scottsboro boys.

The fable of Rosa Parks is fundamentally a Southern story – and so it becomes hard to see the actual Rosa Parks who spent more than half of her political life fighting the racism of the Jim Crow North. In the 1960s, she is living, as she puts it, in the ‘heart of the ghetto’ – and describes Detroit as the “promised land that wasn’t.” And so, as she had in Montgomery, she set about to challenge the racial caste system in jobs, housing, schools and policing that beset her new hometown.

Parks’ political life demonstrates the connections and overlap activists made between the civil rights and Black Power movements. By the late 1960s, her longstanding commitments to self defense, black history, criminal justice, independent black political power and economic justice intersected with the growing Black Power movement, and she took part in many events and mobilizations. She attended the Black Political Convention in Gary and the Black Power conference in Philadelphia. Helping to run Detroit Friends of SNCC, she journeyed to Lowndes County, Alabama, to support the movement there, spoke at the Poor People’s Campaign, helped organize support committees on behalf of black political prisoners and paid a visit of support to the Black Panther school in Oakland, CA. But our vision of militancy often doesn’t include reserved middle-aged women activists, and so, in many ways, Rosa Parks was hidden in plain sight during the Black Power era.

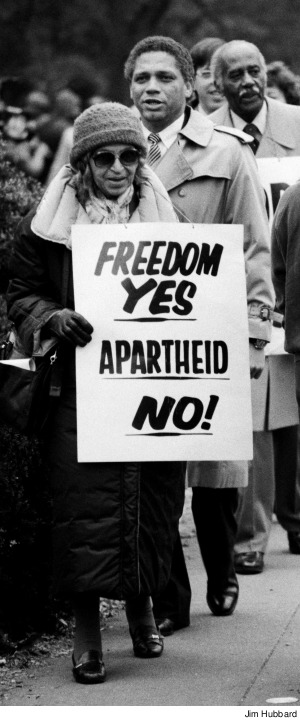

Internationalist in her vision, Rosa Parks’ vision of justice was a global one. She was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam. In the 1980s, she protested South African apartheid and U.S. complicity, joining a picket outside the South African embassy. And eight days after 9/11, she joined other activists in a letter calling on the United States to work with the international community and urging no retaliation or war. Rosa Parks is often celebrated for her long-ago contribution to history – and yet her political work continued to take on the justice issues of our time.

______________________________

An earlier version of this article was published January 30, 2013 on Biographile.com.