|

As “right-to-work” laws proliferate, it’s worth remembering that they originated as a means to maintain Jim Crow labor relations in the South and to beat back what was seen as a Jewish conspiracy.

No one was more important in placing right-to-work on the conservative political agenda than Vance Muse of the Christian American Association, a larger-than-life Texan whose own grandson described him as “a white supremacist, an anti-Semite and a Communist-baiter, a man who beat on labor unions not on behalf of working people, as he said, but because he was paid to do so.”

The idea for right-to-work laws came from Dallas Morning News editorial writer William Ruggles, who on Labor Day, 1941, called for a constitutional amendment prohibiting the closed or union shop. Muse visited Ruggles soon thereafter and secured the writer’s blessing for the Christian American Association’s campaign to outlaw contracts that required employees to belong to unions. Ruggles even suggested to Muse the name for such legislation – right-to-work.

Muse had long made a lucrative living lobbying throughout the South on behalf of conservative and corporate interests, or, in the words of one of his critics, “playing rich industrialists as suckers.”

Over the course of his career, he fought women’s suffrage, worked to defeat the constitutional amendment prohibiting child labor, lobbied for high tariffs and sought to repeal the eight-hour-day law for railroaders.

AN EMPLOYER-BACKED RACIST

Muse first attracted national attention through his work with Texas lumberman John Henry Kirby in the Southern Committee to Uphold the Constitution. That committee sought to keep President Franklin D. Roosevelt from being renominated in 1936, on grounds that the New Deal threatened the South’s racial order.

Despite its name, the Southern Committee received funding from prominent Northern anti-New Deal industrialists and financiers, including Alfred P. Sloan and the du Pont brothers.

Among Muse’s activities on behalf of the Southern Committee was the distribution of what Time called “cheap pamphlets containing blurred photographs of the Roosevelts consorting with Negroes,” accompanied by “blatant text proclaiming them ardent Negrophiles.”

In 1936, Muse incorporated the Christian American Association to continue the fight against the New Deal, offering up a toxic mix of anti-Semitism, racism, anti-communism, and anti-unionism.

Supporters of the Association considered the New Deal to be part of the broader assault of “Jewish Marxism” upon Christian free enterprise. The organization’s nominal head, Lewis Valentine Ulrey, explained that after their success in Russia, the “Talmudists” had determined to conquer the rest of the world and that “by 1935 they had such open success with the New Deal in the United States that they decided to openly restore the Sanhedrin,” that is, both the council of Jewish leaders who oversaw a community and the Jewish elders who, according to the Bible, plotted to kill Christ.

According to Ulrey, this “modern Jewish Sanhedrin” – which included Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and NAACP board member Rabbi Stephen Wise – served as the guiding force of the Roosevelt administration and the New Deal government. Muse voiced the same anti-Semitic ideas in simpler terms: “That crazy man in the White House will Sovietize America with the federal handouts of the Bum Deal – sorry, New Deal. Or is it the Jew Deal?”

BREAK LABOR’S POWER

By the early 1940s, the Christian American Association, like many Southern conservative groups, focused much of their wrath on the labor movement, especially the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The Association solicited wealthy Southern planters and industrialists for funds to help enact anti-union laws and thus break the “stranglehold radical labor has on our government.”

Muse and his allies continued to claim that Marxist Jews were pulling the national government’s strings, but changed the membership of this supposed cabal to CIO leaders like Lee Pressman and Sidney Hillman. The Association insisted that the CIO was sending organizers to the rural South to inflame the contented but gullible African-American population, as the first step in a plot to Sovietize the nation.

By the early 1940s the waves of anti-Semitism emanating from the Nazis in Germany and the prospect of American involvement in the war convinced the Association to tone down its anti-Semitic rhetoric. As Muse’s co-worker and wife, Maria, confessed in 1943, “Christian Americans can’t afford to be anti-Semitic outwardly, but we know where we stand on the Jews, all right.”

Muse and the Christian Americans initially had little luck selling their right-to-work amendment but did have success peddling a prepackaged anti-strike law to planters and industrialists first in Texas and then in Mississippi and Arkansas. This law made strikers, but not strikebreakers or management, criminally liable for any violence that occurred on the picket line.

For a fee, Muse and his organization would lobby legislators and mobilize public support through newspaper advertisements, direct mail campaigns and a speakers’ bureau. In Arkansas, Muse portrayed the anti-strike measure as a means to allow “peace officers to quell disturbances and keep the color line drawn in our social affairs” and promised that it would “protect the Southern Negro from communistic propaganda and influences.”

RIGHT-TO-WORK AMENDMENT

The Arkansas Farm Bureau Federation and allied industrialists were so pleased with the Christian American Association’s success in passing the anti-strike measure that they agreed to underwrite a campaign in 1944 to secure a right-to-work amendment for the Arkansas Constitution. This placed Arkansas alongside Florida and California as the first states where voters could cast ballots for right-to-work laws.

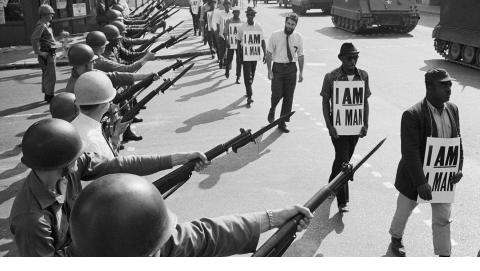

During the Arkansas campaign, the Christian Americans insisted that right-to-work was essential to maintain the color line in labor relations. One piece of literature warned that if the amendment failed, “white women and white men will be forced into organizations with black African apes…whom they will have to call ‘brother’ or lose their jobs.”

Similarly, the Arkansas Farm Bureau Federation justified its support of right-to-work by citing organized labor’s threat to Jim Crow. It accused the CIO of “trying to pit tenant against landlord and black against white.”

In November 1944 Arkansas and Florida became the first states to enact right-to-work laws (California voters rejected the measure). In both states, few blacks could cast free ballots, election fraud was rampant and political power was concentrated in the hands of the elites. Right-to-work laws sought to make it stay that way.

A version of this article originally appeared in Labor Notes.